Perched on a makeshift stage, a trio dressed in wool ponchos sings pirekuas, the region’s most acclaimed and loved musical genre in a mix of Purépecha and Spanish. Despite their upbeat and soft-sounding melodies, the lyrics of the songs describe a time of fear and destruction when, eighty years ago, the Paricutin, the world’s youngest volcano, emerged from a cornfield and devastated the region. Stallkeepers are busy selling quesadillas, chips, sodas, and beers to the expectant crowd, gathering around a bonfire installed inside a miniature volcano. This contrast between apparently joyful festivities and solemn commemoration marks the evening’s atmosphere in Angahuan, Caltzontzin and San Juan Nuevo in Michoacan, Mexico. Several uniformed and heavily-armed municipality police stand nervously watching the horizon. These days, this is fraught territory, as organized crime groups dispute control over the area. This is also the first time that an event like this is staged on-site at the place known locally as las ruinas [the ruins], a shorthand for the remains of the old San Juan Parangaricutiro church, the only surviving structure of an entire town buried under the thick and rugged lava.

Image 1. Bonfire inside the miniature volcano in Las Ruinas. Photo: Sandra Rozental.

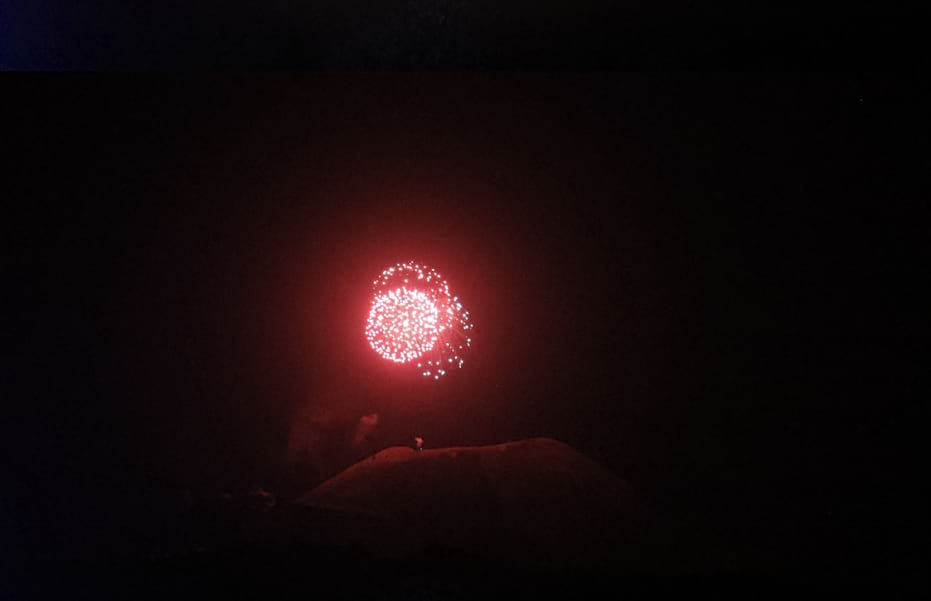

Although this uncanny landscape, a combination of human and non-human architecture, has been an iconic tourist attraction for decades, tonight it shines under the lights of commemoration. Authorities from San Juan Nuevo, the locality where the residents of the devastated town were relocated, installed strings of blue strobing LED lights to illuminate the ruins. Their blinding glare made the silhouette of the volcanic cone barely visible in the distance. At 9 pm, the mountain began emitting incandescent explosions. These were not the product of molten magma emerging powerfully from the earth’s core, as had been the case decades ago, but purpose-made fireworks, spinning loudly, spitting orange and red heart-shaped sparks into the sky. National tourists and local visitors silently admired the spectacle sitting uncomfortably on the sharp rocky surfaces by the ruins; others chose panoramic vistas of this volcanic surrogate from the terrace restaurant and tourist center in the nearby town of Angahuan.

In Mexico, we are fond of anniversaries. Our political culture relies heavily on commemoration, centennials, and bicentennials. The volcano is no exception. Every decade that passes, around the volcano’s birth on February 20th, its anniversary is marked both by locals, who commemorate its eruption and its destructive effects, and by academic institutions and government bodies celebrating its emergence as a milestone for the earth sciences and for Mexican national and regional history.

Image 2. Program flyers for community and state government’s events commemorating the Paricutin’s 80th anniversary posted on the wall of the municipal office in Angahuan. Photo: Sandra Rozental.

But a volcano is not a military victory, nor a conquest, nor a war with friends and foes to be honored or shunned. It is an eruption, a geological emergence, a sudden and unexpected event that physically opens and breaks the earth’s surface, reminding us that we travel on an unwieldy, unknown, and capricious fireball. A volcano might then be imagined as an interstice, a liminal space that for a brief moment in earthly temporalities, brings together history and deep time. It’s an event, but it is also a place where the forces of what we call “nature” and of human historicity and territoriality collide. How, then, do humans memorialize the kinds of disruptions and transformations, even violence, caused by such phenomena? How might those who endure its effects up close mark a volcano’s birth and subsequent destruction of their territory and livelihoods?

Image 3. Fireworks from the crater, February 2023. Photo: Lorena Casillas

One of the stall owners, at Las Ruinas known as “Cachuy,” is the event’s main organizer. Nervously feeding the miniature volcano with gasoline and firewood, he is charismatic and clearly enjoys his role as MC. Just before the fireworks, he gathers a group of children and curious visitors (ourselves included) and leads us down a barely visible pathway in the otherwise ash-covered landscape. Our feet sink into the thick powdery surface. Cachuy stops abruptly and asks for silence. In a solemn voice, he explains that we are standing on what is left of the old town’s main street. As he guides us in the dark, he tells a story: “The night that the town was finally evacuated, in May of 1944, elders say the whole street lit up with a long line of flickering lights. They headed down the street from the cemetery like a row of candles. It was the souls of the dead following the living. Even the dead left this place to join their families before the lava covered it.” Cachuy pulls back the branches of a tree, drawing our attention to a pile of crumbling stone masonry. “This is what is left of the walls of a house,” he tells us. A young man walks cautiously amongst the rubble for a few minutes. Almost in a whisper, he murmurs: “I think this was my family’s home.”

Eighty years ago, in February 1943, the Paricutin famously emerged in these lands in Michoacan, becoming the first volcano to be registered during its entire lifespan. The eruptions lasted for almost a decade, completely transforming the region where entire villages were destroyed by lava or devastated by the immense amounts of ash and toxic gasses that the volcano spewed into the air. During this time of hunger, destruction, and forced migration for local residents, scientists, photographers, filmmakers, and artists flocked to the area to witness, as well as to capture, the spectacular displays of incandescent wonder. The Paricutin became an international sensation. Its images went around the globe, featured in artworks by Mexico’s most renowned artists and portrayed in different views, up close and from afar, in thousands of glass plate negatives, black and white and color photographs, and even 35 mm film.

In February of this year, we set out to find out. Although we had attended previous anniversaries, we were especially interested in how the volcano’s 80th anniversary was commemorated. This time period–80 years–was the equivalent of a human lifespan, and therefore, marked the fading possibility of eyewitness accounts, setting the stage for strategies of commemoration that went beyond human memory.

We attended the commemorations organized by three of the Purépecha communities most affected by the Paricutin’s eruption: Caltzontzin and San Juan Nuevo, the resettlements of the disappeared Combutzio and San Juan Parangaricutiro, relocated to lands on the outskirts of Uruapan, Michoacan; and the neighboring Angahuan, a town that survived the lava flows, becoming the point of access to the extinguished cone and the ruins, elsewhere surrounded by the inhospitable terrain known in Spanish as “malpais,” or badland.

Thinking of commemoration as a reiterating strategy for making memory palpable, during these events, we found constant tensions between an impulse to reenact the spectacularity of the geological event–which is also a way to sustain tourism and its subsequent consumption economy; a collective need to compile and display information and images showing the volcano’s past and its effects in the communities’ present; and a wary discomfort, even reprimand, from some elders angered by the celebratory tones that concealed the painful aftermaths of the Paricutin’s emergence in the histories and lives of current inhabitants.

A recurrent theme in local inhabitants’ efforts to commemorate, often in collaboration with researchers like ourselves and with cultural institutions, has been to repeat the eruption in image form, with film screenings and photographic exhibitions on the volcano, particularly on its destructive effects on local towns. Through these activities, commemoration is also a space to affirm senses of ethnic, linguistic, and territorial belonging in a complex and historically rooted context of land disputes, organized crime, and cultural and economic dispossession. The images we share here, which are part of a work in progress, open a visual dialogue on the tensions, possibilities, and also failings of the eruption’s commemoration.

Image 4. A girl watches an itinerant photo exhibit, co-organized by geologist Pedro Corona and historian Juana Martínez with the authorities of San Juan Nuevo, Caltzontzin and Angahuan. The exhibit was part of the anniversary commemoration activities. Photographs were selected from different scientific archives that Corona and Martínez’ team compiled into an “object-box” as a strategy to return physical archival images and documents to communities affected by the eruption. Photo: Sandra Rozental.

Image 5. Photographic exhibit “Surviving a Volcano”, co-organized by Gabriela Zamorano, Sandra Rozental, Manuel Sosa Lázaro, Lorena Casillas and the community museum Kutsikua Arhakucha. Photo: Lorena Casillas.

Image 6. Stage prepared for the Paricutín Anniversary in Caltzontzin featuring regional dance and music. Photo: Gabriela Zamorano.

Image 7. Kurhaticha dance, presented by youth from Arantepacuain the Central Plaza of Angahuan as part of the commemorative program of the Paricutin Anniversary. (Photo: Lorena Casillas).

Image 8. Purépecha researcher Manuel Sosa interviews María Guadalupe Anguiano Aguilar, a resident of Angahuan, about her childhood memories of the eruption in San Juan Parangaricutiro where she was born and lived until 1944. Photo: Sandra Rozental.

Although commemoration is highlighted in anniversary events, it is also present in everyday forms of interacting with remains, images, and replicas that refer to the eruption and its aftermaths. Catzontzin’s residents, for example, commemorate the volcano every day, as the Saint images rescued from Combutzio and the old bronze bell from the disappeared church were reinstalled in the town’s new church and are now worshiped there.

Image 9. The highly venerated figure of Divino Santiago and the together with a dozen Saint images, were rescued from Combutzio and transported to Caltzonzin where they are venerated in the contemporary town church. Photos: Gabriela Zamorano and Sandra Rozental.

Image 10. Bronze bell rescued from Combutzio and transported to Caltzonzin’s town church. Photos: Gabriela Zamorano and Sandra Rozental.

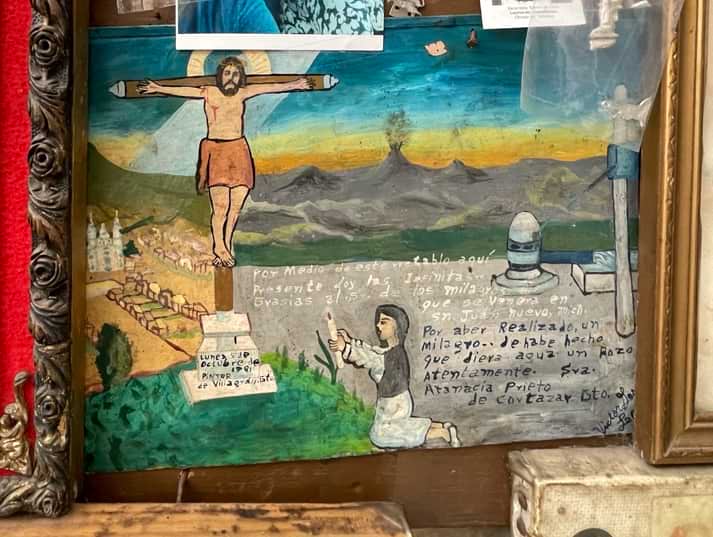

In San Juan Nuevo, where the residents of San Juan Paranguricutiro were resettled, a small museum next to the rebuilt church houses a collection of ex-votos. In these images, another kind of commemoration and record, the volcano is shown as the cause of great suffering, a source of desperation that people prayed and went on pilgrimages to escape.

Image 11. An ex-voto of a woman thanking the Señor de los Milagros for having found a water well in San Juan Nuevo, the community where people from San Juan Parangaricutiro were resettled. Photo: Sandra Rozental

One of the first attempts at commemoration once the village of Combutzio was resettled in the outskirts of the city of Uruapan was the mural Exodo de la población de la región del Paricutin, painted in 1950 by two of the country’s important muralists, Alfredo Zalce and Pablo O Higgins in the corridor of the newly built school, a building associated with the Mexican welfare state that had organized the town’s relocation. Now in a rather poor condition and walled in when this part of the school was transformed into the headmistress’ office, the mural continues to be a testament to how the volcano and its aftermath endure in the daily lives of the residents of Calzontzin forced to flee from its afflictions.

Image 12. Mural Éxodo de la población de la región del Paricutin by Alfredo Zalce and Pablo O Higgins, now the backdrop of the headmistress’ office. Photo: Sandra Rozental.

Another set of murals was commissioned by town authorities to José Luis Soto, an artist from Morelia, to mark the volcano’s 50th anniversary. The artist used glass shards and pieces of volcanic rock to make a multicolored mosaic showing a battle between good and evil incarnated in the local Saint, el Señor de los Milagros, and the devil. The mural commemorates the eruption as well as local religion and beliefs regarding divine punishment for earthly sins.

Image 13. Mural by José Luis Soto in Angahuan showing the volcano as the result of the battle between good and evil. Photo: Sandra Rozental.

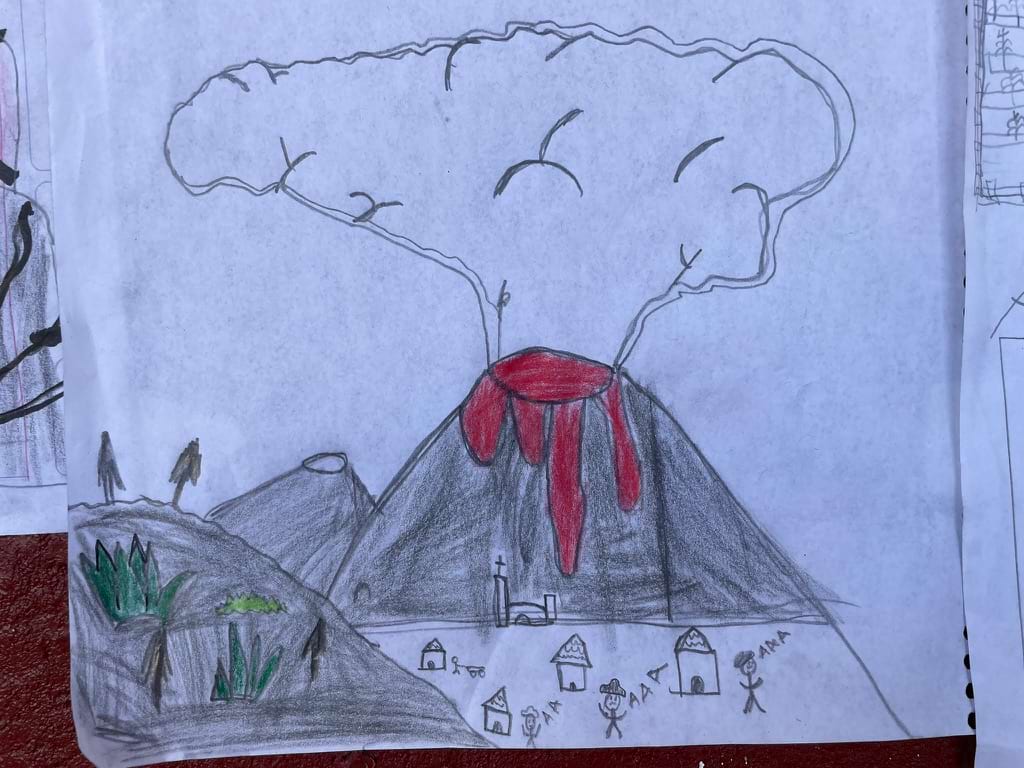

While these murals constitute enduring interpretations of the volcano’s emergence, annual commemorations also reinforce strategies to interpret, remember, and reenact this history, particularly with youth and children. In all the places we visited, community representatives organized a competition where schoolteachers and their pupils were invited to represent the volcano and its effects in drawings and clay models. Hundreds of color drawings lined the buildings that make up the towns’ main squares, featuring human figures and tiny cattle running away from red rivers of lava.

Image 14. Women look at the exhibition of children’s drawings in the Central Plaza of Angahuan. Photo: Sandra Rozental.

Photo 15. Detail of a drawing about the Paricutin eruption in the Central Plaza of Angahuan. Photo: Sandra Rozental.

In Caltzontzin, the award was unanimously given to a model by a 12-year-old that, like the mural made thirty years ago, featured the volcano as well as the Catholic Saint images in the local church protecting town residents from the dangers of geology. Despite the fact that this child’s life is now temporally and geographically distant from the Paricutin, her present, like that of all the children involved in the commemoration activities, is defined by the intersection of geological and human time. This generation’s awareness and intimacy with the Paricutin is reenacted and kept alive through practices that constantly recreate the volcano and recall its aftermaths.

Photo 16. Liczi Gabriela Diaz Trejo from Caltzontzin showing her clay model. Photo: Gabriela Zamorano

The authors would like to thank Manuel Sosa, Simón Lázaro, Esperanza Azucena Padilla Anguiano, Jesus Velázquez Gutiérrez (Cachuy), as well as Pedro Corona and Juana Martínez for their welcoming support and guidance during the 80th Paricutin Volcano Anniversary in Angahuan, Caltzontzin, and San Juan Nuevo. We also thank Lorena Casillas and Paula Arroio for their assistance during this visit. Funds for this research were provided by the Imagining Futures project (https://imaginingfutures.world/)