In this piece I meditate on a conversation I had with my key interlocutor, Aleksandar Kecman, about Google tracking and our reflections upon first encountering my digital footprint.

I met Aleksandar in Belgrade, where I did research among insomniacs exploring how the experience of time (and tangentially, space) figures in their lives. Being an insomniac myself I felt chronically out of synch with the rest of society—people close to me and their work and sleep schedules, the rhythms of socializing, and the idea of productive life well spent in time—and this feeling tracked with my interlocutors. Many of the problems the sleepless face are quandaries of time. How are the everyday practices of insomniacs shaped by local and broader understandings of what it means, temporally, to lead a “good life,” or a productive life, within a society that values grind and hustle?

This piece is not about insomnia. Insomnia here figures only as an entry point for discussing anxieties about daily habits. While my research revolves around sleep, ultimately I am interested in everyday routines and how these correspond to notions of the good life and fears around “time-wasted.” These ideas differed depending on the social positioning and individual values of my interlocutors, but all of them were fearful about how their everyday routines represented and reflected—or not—the image of people they were striving to be.

This piece approaches these questions about life, time-waste, routine, and restlessness through a different lens. Namely, Google tracking data serve as an elicitation device and a conversation starter to help me think about the everyday routines and rhythms of the lives of people I have talked with, as well as my own routines.

Taking the ethnographic fact that routine is repetition as a starting point, I meditate on the value of routine and how it is couched in our daily life. Do Google timelines represent a snapshot of our lives in time and space? To what extent are they related to how we live our “actual lives?”

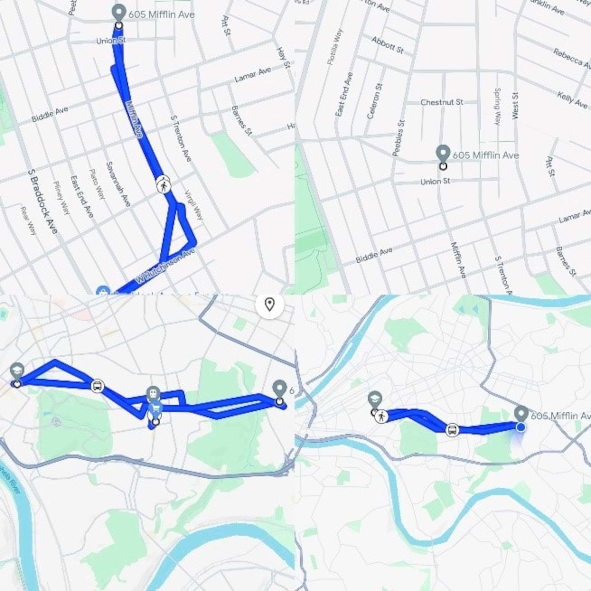

When I first realized that Google was tracking me (and that I too could see my data), I fell into a spiral obsessing over and analyzing my movement for the past four years. I did not enjoy my digital footprint.

A snapshot of the author’s time data for the previous four months. Screenshot by author.

A snapshot of the author’s movement data for the previous four days. Screenshots by author.

I am not subject to strict schedules. I enjoy relative temporal and spatial freedom. Yet, my days and months had a predictable regularity and rhythmicity. My strict choices of time investment crumble on weekends and during holidays, even though I am not bound to an external time-keeper. Aleksandar disabled his Google tracking a long time ago, so he doesn’t have access to his own data. Yet he imagined it would probably look similar to mine. He did not seem too worried about it. Even though he is very anxious about the ways in which he spends his days, he didn’t believe that this type of data has value because they are decontextualized. Google can’t possibly know what happens between tracked movements and check-ins.

The bulk of scholarship in the social sciences and humanities about how qualitative aspects of human lives get converted into quantified data support Aleksandar’s claim about the de-contextualization inherent in data sets such as Google tracking. While I agree with this, when confronted by data about my own use of time and movement through the world, I nonetheless began to question whether, and to what extent, the data represented a real reflection of my days. For me, seeing the results triggered critical reflection on what the building blocks of my life were, in line with Minna Ruckenstein’s claims that “the data does not displace or freeze but rather enhances and enlivens self-narratives” (2014, 80).

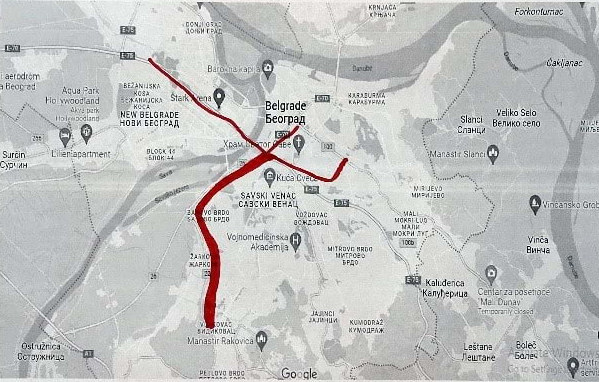

While Aleksandar and I did not agree on the capacity of Google timelines to tell us something meaningful about our lives, we arrived at an intersection where our anxieties meshed. Both of us chose “non-traditional” life paths; I am a graduate student and Aleksandar is an actor. We chose these paths to escape the clutches of a nine-to-five life rhythm. When faced with my digital footprint I realized I had still created my own spatially and temporally predictable day. I lamented my own routinization, feeling disgusted by the predictability of my movements through space and time. Aleksandar reflected on his own movement, both spatially and temporally. Even though he did not have any quantifiable data, through our conversation, he engaged in internal map-making of his everyday movement. Inspired by how Google tracked me, Aleksandar and I reconstructed his movement and mapped it onto a blank paper map of Belgrade. These movements were a product of his time-investments that are embodied in daily routines.

Reflecting on this Aleksandar shared: “My movement would consist of the same thing, you know when you run and track it in an app, if you run back and forth on the same route, the line will get thicker? In my case, I think there would just be many thick lines in the same space; that makes me sad. You know when you walk the same road so many times, and then you ask yourself, what would happen if I just swerved onto a different street now? Sometimes I feel like living in a dream.”

This map represents after-the-fact drawings of Aleksandar’s most-taken routes. The thick line represents the route that repeats day in and day out, while the thinner lines represent the forking in the road that is day-dependent, but repeat on a weekly basis. Image by author.

Both of us ultimately were queasy about repetition and routines, already aware of our (im)mobility, but time and space maps just made it clear to me how “dire” my situation was. And these anxieties were not only our own. Funnily enough we imposed them on ourselves. While the rest of my interlocutors in the same age category could not escape routinization because of their jobs—and habitually complained about this to me— Aleksandar and I could, yet we chose not to. If the everyday is about rhythmic attunements and repetitions, what role then does repetition play when it comes to our inner feelings about ourselves? My concern with the relationship between how I perceive and understand myself and the portrait of myself I was faced with, and Aleksandar’s meditation on daily repetition, drove us to meditate on the question of where our intimate sense of self gets reworked. At that particular moment in time, we tentatively agreed that a big part of who we are gets reworked in our everyday routinized actions—and we didn’t like that. If we wanted to escape routinization, does this mean we also want to escape repetition? And what is it so bad about the two and the people we become through them?

Talking with my insomniac friends I learned that routine is a flip side to spontaneity and curiosity. Conversely, sometimes it was discussed as the other side of chaos. It was always defined in relation to something else, more exciting or even valuable. Routine was presented to me as automated, repetitive, and ritualistic. Every single person I talked to recognized the importance of routines, while simultaneously finding routines stifling and boring.

Perhaps this association is unsurprising. Routine derives from a Latin expression via rupta, a road leading through something, say a mountain or a forest. It means a well-trodden path. Two other words share the same root: the word route and rut. Rut first denoted the traces a wheel would carve out in the road, but in the mid-nineteenth century it acquired the meaning it still has today. Routine and rut are in close contact. In contrast to that are spontaneity and deliberately thought-out activities. The conventional and repetitive is relegated to the what-needs-to-be-done realm of life—to what we might call maintenance work. Both of these did not seem to have any purpose other than “keeping up with life” or “anchoring us.” Aleksandar and I were privy to these understandings. With no external entity (e.g., job) forcing it, why did we still engage in constant repetition? Were we in a rut?

Routine, as we vernacularly understand and practice it, is a cornerstone of the grind. Tara McMullin claims that the morning routine is the essential part of the hustle culture. In their essence morning routines are preparation rituals, one of many unpaid tasks we are taught to engage in before we formally enter the space of paid labor (or meaningful life pursuits). McMullin claims that the celebration of these routines only benefits the employers—or self-employers for that matter, or the striver and doer—since they are performed to keep us marginally healthy and ready. I believe that this can be extended to routines in general, which is what I mean by maintenance work. They are understood as accessory actions. Google tracking and how it is used plays into that. It is a part of the optimization economy, along with Fitbits, Apple Watches, and the like. The optimization industry drives us to squeeze the most of everything from our daily activities without overspending time on them.

The can of worms that Google opened for me is the problem of time and how I use it—a cornerstone of optimization discourses. Am I spending my time in ways that will land me somewhere? Am I doing enough meaningful things? What do I do for days upon days when I end up glued to my house as Google Maps showed me (and there are plenty of those)? Why do my routines reflected in Google timelines look so repetitive? Am I experiencing and doing enough? Will my inner life rot? Am I in a rut?

I opened this piece with a joint meditation between Aleksandar and myself where we both expressed anxieties around the questions I just posed. We both felt too sedentary, wasting our time and not being agentive enough. We escaped the nine-to-five grind only to end up anxious about the lack of grind. In her book about time, Jenny Odell reflects on Zhuang Zhou’s story, “The Useless Tree,” in which he meditates on worthlessness and usefulness through a story about a carpenter who deems an old oak worthless. The oak was not fit for producing timber. Paradoxically this worthlessness made the oak grow old and big and untouched. Odell uses this story and metaphor as a symbol of “resistance in place,” a call for shaping oneself into less exploitable and appropriable subjects (2019, xvi). She is referring to the attention economy and our digital footprints, but also to the general need of incessant moving and doing rather than attending or observing.

Aleksandar thought that his repetitive movements felt “like a dream,” like he is perpetually in an inactive state. By taking his assessments seriously, infusing them with my own anxieties, and juxtaposing them to Odell’s call of staying put, we might ask: What is qualitatively “worthless” about being in a dreamlike state? Could we, by being non-agentive, see things in a different way? What kinds of politics of life can emerge if staying in the rhythm(s) is valorized not only as maintenance work, but an integral part of self-realization? And do we need to switch off our Google tracking to achieve this?

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Paige Edmiston.

References

Odell, Jenny. 2019. How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, Melville House.

Ruckenstein, Minna. 2014. Visualized and interacted life: Personal analytics and engagements with data doubles. Societies, 4(1), 68-84.

1 Comment

Thanks for your post. I would like to share my experience on this. I’ve also had insomnia forever and have recently been freed from the burden of a 9-5 routine (not by choice). Initially I looked for a new job, then I realized that I no longer wanted this type of life. The next question was how to best use my time while remaining spatially tied to my family’s routines. What followed was a crisis of identity and purpose in life and a long process of subjectivation (still ongoing), during which I almost became a chef, I undertook new studies (anthropology…) and I joined a group of self- and mutual-help. All this didn’t change my space routines much, but it changed me, profoundly. Therefore, I would strongly suggest integrating your analysis with the role of the “movement of the imagination” (in addition to spatial movement) as foundational to the processes of self-creation.