Writing inequalities

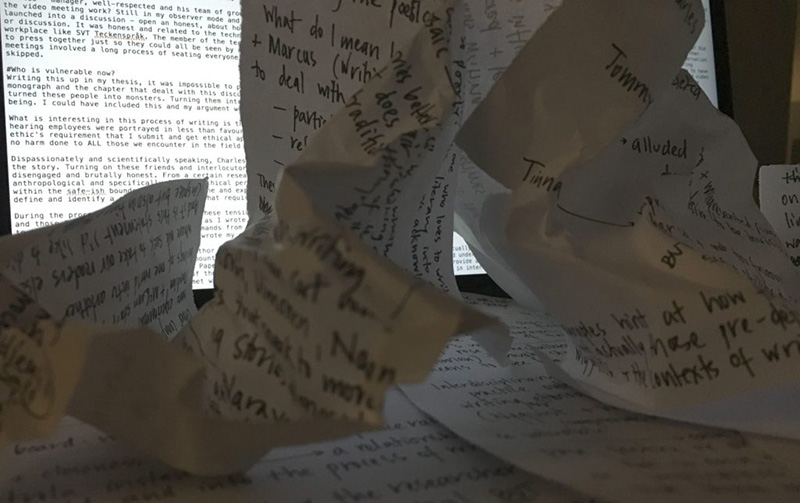

Writing disability through rewriting representations of inequality and vulnerability. Image: R. Cupitt 2018

When writing inequalities, the language we use and our writings betray the power dynamics and the unequal relations that stem from the world we as researchers come from. This post explores how these inequalities play out in the worlds we embed ourselves in as outsider researchers and are apparent in what we write through a reflection on my own research with dDeaf television producers and actors in Sweden.

To give some context, I want to reflect on the Disabling Technology blog series and its goals to explore how inequalities and technologies are woven into disabled worlds and become players in re-enactments of disability and people’s identities. In choosing the authors for the nine posts, I have intentionally woven together anthropological, STS, and design perspectives and approaches to technology and disability to highlight different ways of acknowledging and critiquing inequality and normative assumptions about ability. Despite their divergent points of origin, the various posts have guided me through a key issue when it comes to disability studies: how do we as researchers engage with and co-construct disability through our collaborations, participatory frameworks, democratic ideals, interventions and in our writings?

In general, the series has presented disability not as an inability or lack of cognitive and sensory perception but as a capacity to engage with the world in alternative ways; ways which require certain design approaches (Johansson 2018, Roper 2018), call into question foundational concepts and ways of being in the world (Cupitt 2017b, Theunissen 2017, Taylor 2017, Davis 2018), and critique the global socio-political organizations and disciplinary practices through the lens of disability, calling into question normative assumptions they embody (Alper 2017; Schuler 2018; Cupitt 2017a). As anthropologists however, we are always telling other people’s stories. Some have said we do this poorly (Taussig 2006:62). I am inclined to agree, on my own behalf, and would add that there is always a chance that we risk presenting an etic and ableist view of disability through our re-tellings.

Reflecting on my own contributions, I see that the work I am doing translates and communicates disability to a particular audience—designers and engineers—who represent the key figures in technology development and those most likely to reinforce exclusionary societal norms that create inequalities. Yet as a researcher, despite ethnography’s underlying participatory ethos, I wonder if I am not complicit through similarly exclusionary practices. Does the noise my writings make disturb the voices of those perfectly ready to speak for themselves, and already doing so with clarity? Holding on to this unease and questioning the anthropologist’s right to engage in these discussions and ‘staying with the trouble’ as Haraway (2018) put it, is one way to see myself through this crisis.

Writing vulnerabilities

The rest of this post is not about questioning the role of the anthropologist, but about how to make sure this uneasiness makes its way into our texts. Part of telling other people’s stories well is knowing the audience, and in my particular case it is about telling stories about dDeaf ways of being in the world as they interweave with hearing norms and technological entanglements for designers and engineers. Not only do I, as a writer, need to know my audience, but I need to know myself as a producer of knowledge. At first glance, I seem to be the intermediary (Merry 2006). I occupy an uncomfortable in-between space in relation to those I study with and those I write for that potentially undermines and weakens anthropology and the knowledge that it creates. To harken back to the first post in the series, ethnographically generated insights are regarded as imprecise, running counter to the desire for concrete implications for design (Dourish 2006). Simply acknowledging the cultural relativity of a list of implications for design and arguing for the place of thick descriptions relegates the anthropologist to the same dark corner as the unwanted design critic and their Nelly-no-friends, the technophobe.

To further confound the matter, as I have written elsewhere, the snake-like researcher can curl back and bite the very people they study with (see Anthrodendum blogpost, Cupitt 2018). This latent danger seems especially strange when it is put alongside the ways in which I, as an anthropologist, work hard to establish that all-important rapport. Part of the rapport-building mythos that we as anthropologists share is perhaps a single memory of an event or moment of realization when we noticed that we were no longer the outsider in a field of strangers. Before this instant, we are extremely vulnerable and often without support.

For me, the Geertzian ‘police raid moment‘ (1972) came when someone told me that I had begun signing while talking—not how you generally sign, but a first step on the road to communicating in sign language. I was made to understand that this signified for the Swedish television’s employees that I was slowly becoming a part of the shared dual language practices at the SVT Teckenspråk—my primary field site and Swedish television’s division for programming in Swedish Sign Language.

These moments of mimesis during fieldwork are critical to how we as researchers form ourselves during that part of the ethnographic fieldwork process (see the classic example from Taussig, 1993:193ff.), but what happens when we are writing? Do traces of this rapport remain in our process, and how do they alter? Does the physical and temporal distance from the field and the people there translate into our texts as we sculpt them into a shape that complies with the conventions of scientific knowledge-making? I argue that relations of care do flow on into the writing phase, but that there is a tension between them and the snake-like researcher who suddenly rears its head in answer to the call of Science with a capital S. This changes the dynamic and effects who is marked as ‘vulnerable’.

The inequalities of ‘vulnerability’

The Ethics Board and applications for ethical approval are perfect examples of the double-edged sword of ‘vulnerability’ and the inequality inherent in the concept and its implementation in research practice. In applying for ethical approval, I was notified that I was dealing with a vulnerable group of people—more vulnerable than a hearing group of state employees—and that their identities should be protected at all costs. ‘Protection’. Without being given the right to themselves choose whether they were to be visible and named in my research, the Ethics Board had made the decision that SVT Employees with hearing impairments and who were deaf, or identified as Deaf, were to be protected on the grounds of their physical inability to hear. Reinforcing the normative understanding that deafness leads to a lack of ability to hear (and by extension, an inability to make decisions regarding their own wellbeing and conditions of participation in society), the Ethics Board defined deafness as a disability in a way that was not shared by SVT Employees. Far from vulnerable with respect to their capabilities, the group at SVT Teckenspråk play a central role in the Swedish dDeaf community and provide media content in Swedish Sign Language. This can put them in a vulnerable position, for instance as celebrities or the targets of critique, but it is no less true of the hearing employees and interpreters at SVT Teckenspråk—all of whom are equally public figures. Yet the Ethics Board did not comment on the need to protect SVT employees in general, only those with hearing impairments or who were dDeaf. This top-down assignment of who could be known and who was to remain anonymous meant those ready to be seen were made invisible, specifically by me, in accordance with the dictates of an Ethics Board not necessarily considerate of the ‘many ways of being dDeaf’ (Monaghan, Nakamura, Schmaling & Turner 2003).

Once I began writing, it turned out that the dDeaf were no longer vulnerable, as I had observed in detail the multiple ways in which communication at SVT Teckenspråk was carried out. Instead, in earlier drafts of my text I had to work hard not to portray the hearing employees at SVT in a detrimental way. Open and frank conversations I had with employees about working in a dDeaf and hearing workplace meant that I had gathered data suggesting that hearing employees were sometimes slow to adopt Swedish Sign Language (one of the official languages at SVT Teckenspråk, the other being Swedish); and that this affected workplace equality and relations between dDeaf and hearing employees. The dDeaf employees, on the other hand, were experts in communication and used a variety of methods to convey meaning (see also similar research on deaf-hearing communication such as Kusters 2015). As my focus moved beyond issues of language and onto those of computer-mediated communication, the distribution of inequality turned out to not discriminate, ironically including deaf, hearing and interpreters—all of whom were disabled by technology to varying degrees (Cupitt 2017c).

A desirable vulnerability?

Pandian and McLean (2017) discuss how the ethnographic text is a vehicle for the reader’s journey. When successful, ethnographic writing takes us into other worlds—or the world of the Other. And yet, this transportation device is contingent on the perceived audience. Saïd makes this point nicely using a concert pianist, his archival recordings, and translations of orchestral pieces to the piano as an example (1983: 31ff.). The ethnographic text is undoubtedly designed and often authored to transmit the experiences of the ‘other’… but what if the reader is reading the text with another purpose in mind? This is often the case when knowledge derived from ethnography is placed within other disciplinary contexts closer to the natural sciences than social science or the humanities.

As anthropologists move more and more into engineering and design circles where they are expected to contribute with intelligible knowledge of value, our ethnographies seem to make us vulnerable. It is a critical and well-known issue that the definition of valuable knowledge is radically different here. Speaking from personal experience, it is still common that reflexivity, acknowledging relativity, and including many voices in an ethnography risks being interpreted as uncertainty, lack of rigor, and that old gem: subjectivity. Not only does it throw into doubt the knowledge we put forward, but it also fails to generate a list of implications for design that can be adopted without hesitation or qualification.

Are there compromises then that we can make? Should we make them? And what direction will we take our writing in next? Pandian and McLean, drawing on de Certeau point to the interiority and exteriority of writing and suggest that we work to write so that the voices never settle (2017: 14). They also point to Anthropology’s commitment to the world beyond itself, and yet I wonder how these vulnerable writings will fare in interdisciplinary settings. Are we as anthropologists are not making ourselves even more vulnerable to critique than we already are? Or is it only through writing to make ourselves vulnerable that we can address inequalities? Is it through this vulnerability to critique (both interdisciplinary and self-critique) that we as anthropologists can move beyond representation and into generative spaces of co-creation.

[Endnote: This blogpost is based on a presentation given at SANT 2018 for the Writing Vulnerabilities panel organized by Henni Alava & Marjaana Jauhola. It marks the last post in the ‘Disabling Technologies’ blog series under my editorship. I hope the series will continue in some form, and a BIG thank you to all the contributors and readers who have engaged with its posts.]

Footnotes

1. By writing “dDeaf” I am signalling an acknowledgement of deafness as a cultural identity (Deaf) founded on the use of sign language as a first language and self-identification as Deaf, but also as a disability (deaf or hearing impaired).

References

Alper, M. 2017 Personal Computing and Personhood in Design and Disability, Platypus, CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2017/06/computing-design-disability/

Cupitt, R. 2018 We Have Never Been Digital Anthropologists, Anthrodendum https://anthrodendum.org/2018/02/03/we-have-never-been-digital-anthropologists/

2017a What the $@#! is an “implication for design”? Platypus, CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2017/03/implication-design/

2017b As if I were blind… Platypus, CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2017/08/blind/

2017c Make difference: Deafness and video technology at work, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden.

Davis, D. 2018 Our Digital Selves: what we learn about ability from avatars, Platypus, CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2018/03/ability-avatars/

Dourish, P. 2006 Implications for design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’06), Rebecca Grinter, Thomas Rodden, Paul Aoki, Ed Cutrell, Robin Jeffries, and Gary Olson (Eds.). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 541-550. DOI=http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1124772.1124855

Haraway, D. 2016 Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene, Duke University Press, Durham, USA.

Johansson, S. 2018 The Power of Small Things: Trustmarkers and Designing for Mental Health, Platypus, CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2018/06/small-things/

Kusters, A. 2015 Ishaare: Gestures and Signs in Mumbai, MPI MMG [film]

Merry, S. E. 2006 Transnational Human Rights and Local Activism: Mapping the Middle. American Anthropologist, 108: 38-51. doi:10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.38

Geertz, C. 1972 Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight. Daedalus, 101(1), 1-37.

Pandian, A. & McLean, S. 2017 Paper Crumpled Boat, Duke University Press, Durham, USA.

Roper, A. 2018 How to Book an Appointment Online when you have Aphasia, Platypus, CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2018/08/appointment-aphasia/

Saïd, E.W. 1983 The World, the Text, and the Critic, Harvard University Press, Princeton, USA.

Schuler, M 2018 ‘Inclusive WASH’ – Contested assumptions about bodies and personhood in a Ugandan refugee settlement, Platypus, CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2018/09/inclusive-wash/

Taussig, M. 1993 Mimesis and Alterity: a particular history of the senses, Routledge, New York, USA.

2006 Walter Benjamin’s Grave, Chicago University Press, Chicago, USA.

Taylor, A. 2017 Becoming more capable, Platypus, CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2017/04/becoming-more-capable/

Theunissen, E. “Becoming Blind” in Virtual Reality, Platypus CASTAC Blog http://blog.castac.org/2017/11/becoming-blind/