(Editor’s Note: This blog post is part of the Thematic Series Data Swarms Revisited)

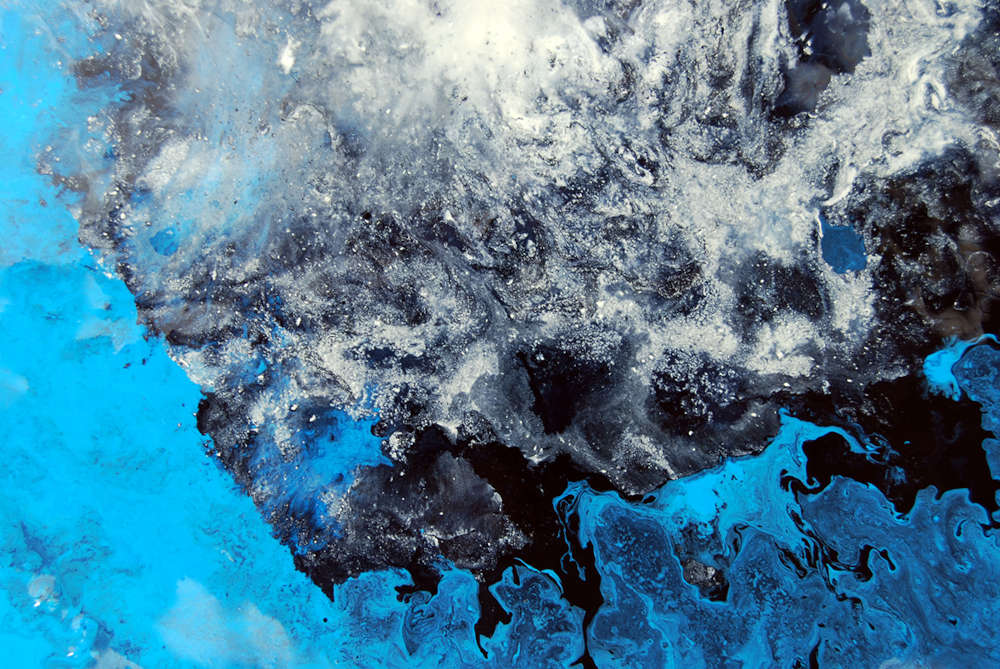

Painting from the art project On Drones and Ectoplasms: Breath of Gaia. ©Angeliki Malakasioti

Introduction

How do concepts such as the human condition, human mind, or collectivity transform in a technologically enmeshed world? And how is our understanding of relationality and agency changed in the context of hybrid tech and built infrastructures, networked systems of control?

This ongoing project constitutes an artistic performative reflection on the entanglement between human agency and technological advances. In this project, the artist[1] focuses on aerial multicopter technological systems—also known as drones—emphasizing the idea of interdependency and control within human-nonhuman systems, which are capable of informing the sustainable and collective futures of our world.

Drones constitute one of the most controversial contemporary technologies. Liam Young notes that drones are “potentially as disruptive as the internet,” underlining their extended presence in urban environments as well as their broad use among the public.[2] Drones have been deployed in relation to surveillance, military actions, public service, or even art. Yet no matter the context of their use, there is an overarching question of how we relate to drone technologies in terms of human agency and control, decision-making and outcome.

The present project embraces the complexities of anthropological and technological systems in a speculative manner, through a multimodal artistic process of research, design, creation, and implementation. Through this approach, the project attempts to interpret theories of posthumanism and cyborgology as well as the relation and interconnectedness between human and nonhuman entities through a poetic, visual methodology.

In the project On Drones and Ectoplasm: Breath of Gaia, the artist makes use of specially designed multicopter drones to construct a visual, painted metaphor for our relation to technology and explore the multiple dimensionalities of mediated agency within a particular human-nonhuman system. Through a process of drone-mediated “action painting,” the artist tries to capture a cartographic representation of the forces, decisions, and multi-scalar events that were carried out on the painting surface. Through this complex interplay of drone, paint, and human agency, the pieces reflect the tensions within the system that produced them. These artworks are a metaphor for contemporary technological encounters; they aim to develop new landscapes that embody our ongoing agonies and engagements with technology and to express at the same time the ecological urgencies of our times.[3]

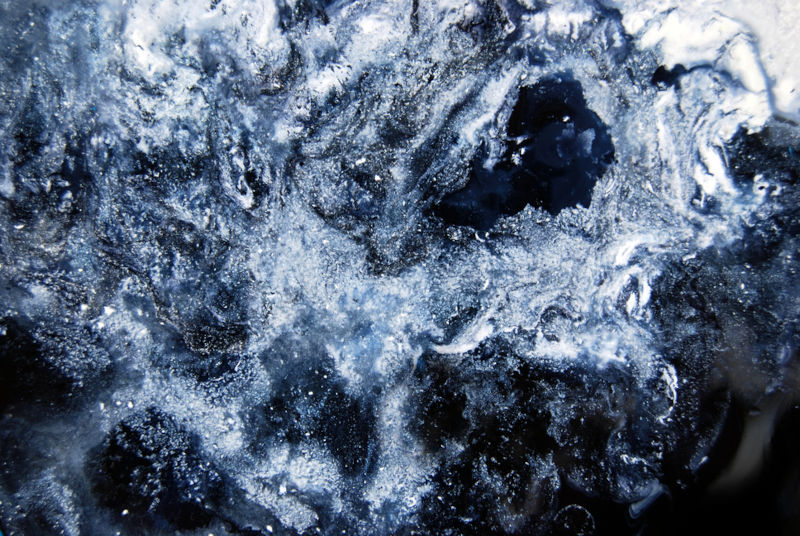

Painting from the art project On Drones and Ectoplasms: Breath of Gaia. ©Angeliki Malakasioti

On Air

How singular, that a moveable breathe of air should be the sole,

or least the best medium of our thoughts and perceptions!

Johann Gottfried Herder[4]

The moving air through our mouths, the breath traveling through human lips, the human language that takes form through sounds and thoughts, signifies our cultural atmospheres, our unique and constantly evolving views of the world. Meanings, perceptions, and ideas adopt an aerial ontology before the spoken material transforms into an agential force, a mediator of communication. Air is “universal” – according to the poet William Wordsworth, we all breathe the same air, as the sky belongs to all: air becomes a communal medium.[5]

Metaphors of aerial infinity are found in many civilizations. Gaston Bachelard[6] relates air with imagination, while ancient Greek philosopher Anaximenes[7] described it as the element of which the soul is made. Both of these associations remind us of the contemporary definition of the word “spirit” as that of the wind.

Inspired by the immateriality of digital culture, in this project, the artist makes use of multicopter drones—one of the most provocative contemporary technological mediums of the air—as a tool to reflect on the pitfalls in our relationship with technology. Through action painting with the use of drones, the artist tries to expand her creative expression through the technological medium, in the same way we extend ourselves in digital worlds. Yet, it is through her artistic process, rather than through her intent, that the faults of the medium are disclosed. It is not what the artist tries to express that is crucial, but rather the human-nonhuman system’s flaws, weaknesses, and imperfections that are exposed through the process of making the piece. The artist faces the challenge of controlling the outcome, of separating eyes and gestures during flight, of reinterpreting the randomness of the drawn landscape, in the same way one experiences common technological encounters in the contemporary world – virtual environments, digital selves, telepresence, hybrid forms of communicating, immersive technological experiences among others. Action painting is manifested as an extension of the artist’s body, but in this project, the human body is divided, augmented, mediated – it becomes a cyborg body exploring its relationship with technology.

Painting from the art project On Drones and Ectoplasms: Breath of Gaia. ©Angeliki Malakasioti

Realization

For the realization of this project, an array of methods was integrated together. In the beginning, a series of experiments with custom-made drones and their architecture was conducted. Drone frames were initially designed in a 3D modeling software that is used for mechanical engineering. Then they were 3D printed using ABS filament, and afterward, they were assembled along with other electrical fixtures (flight controller, drone electronic speed controller, brushless motor, receiver, and transmitter, etc.). The electrical equipment used is often applied in racing and free-style drones’ construction, which allows for greater motor strength, different propeller behavior, and adjustable response to different carrying weights, always in combination with the software used. Then, open-source software as CleanFlight/BetaFlight was used for setting the parameters of the equipment. The overall philosophy of the construction was to create a configurable flying instrument that could be disposable or even destroyed during or after the process.

The artist took on a pilot’s perspective from the ground, at a distance from the main action area.[8] Then the devices were modified and adjusted to temporarily host extra item additions for painting experimentation (objects such as dripping vessels, bottles, brushes, sticks). During the flight, the artist piloted the drone over a canvas lying on the ground, testing different ways of dripping, painting, or splashing, and trying to direct compositions on the landscape-canvas, playing with technical experimentation and its limits. Apart from the painting accessories used, other drone flight aspects were also used for experimentation, such as the propeller rotation, the object’s moving speed, the abrupt speed changes, or the effort to make it hover for a while at a fixed position in the air. After this process a series of images were produced through macrophotography, presenting abstractions of these newly generated landscapes.

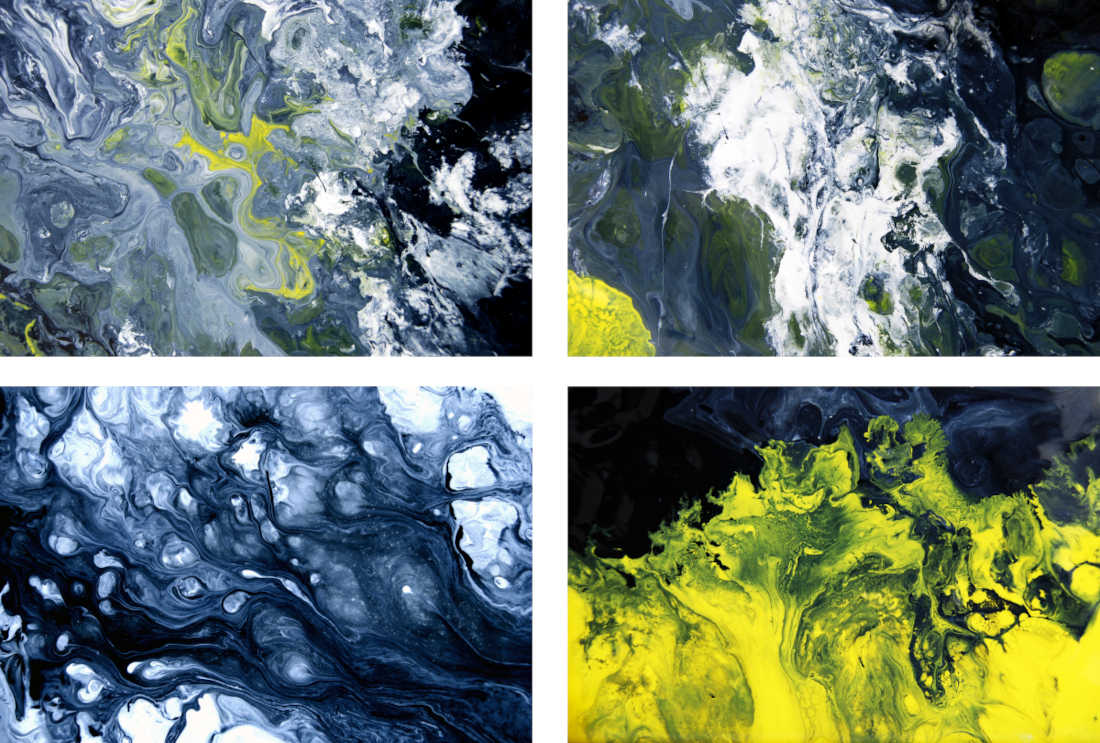

The Landscapes

The close-ups, the ratio, the aerial view from above were all used as tools to demonstrate the conflicting air forces on surfaces, the dynamics, the synergies, the micro-events of materials blooming at this scale. Constructing a metaphor for a new cosmogony and moving from the microcosm of image-creation to the macrocosm of reality, this project ventures a speculative look on what the ‘creation’ of an imaginary Gaia for our future means. This exploration elaborates on the concept of “Gaia-graphy”, which Arènes, Latour, and Gaillardet describe as an exercise in situating the human role in the Anthropocene.[9]

The main objective of the project is to experiment with the potentialities of this process, as well as capture the speculative landscapes that are produced through this hybrid human-drone system. In this context, the artist aims to capture the micro-events that, given the aerial perspective with which drones are often associated, build a metaphor for an altered kind of cultural geomorphology.

Series of paintings from the art project On Drones and Ectoplasms: Breath of Gaia. ©Angeliki Malakasioti

Core Questions

The project tries to build an observation device of speculative collective futures through the construction of a changeable human-drone system as an agent of a creative act.

The project also poses questions about the ways in which we engage with the environment using technology, destabilizing ontologies of hybrid human-machine ecosystems through a symbolic act of mediation and artistic creation that strives to build a common “terrestrial” ground. Through this process, it aspires to comment on the critical situation of collective futures that evolve through our symbiotic relationship with technology and the sociocultural challenges that are triggered through these interdependent ecologies which are so urgent nowadays.

Overall, the project metaphorically constructs a series of new grounds, terrains, and territories for the evolution of new lifeforms, a symbolic act of mediation that discloses the urgent tensions innate in our engagement with nonhuman systems.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Spiros Koutsaridis, mechanical engineer, for the technical support. I am also thankful to Hannah Eisler Burnett for her meticulous copy-editing and remarks and to Christoph Lange for his helpful comments on earlier versions of this post.

Read more of the Data Swarms Series:

Data Swarms Revisited – New Modes of Being by Christoph Lange

Human as the Ultimate Authority in Control by Anna Lukina

Angelology and Technoscience by Massimiliano Simons

Multiple Modes of Being Human by Johannes Schick

Swarming Syphilis: On the Reality of Data by Eduardo Zanella

Fetishes or Cyborgs? Religion as technology in the Afro-Atlantic space by Giovanna Capponi

Notes

[1] Editor’s note: Artist and author are the same person.

[2] Liam Young, Elevation Documentary: How Drones Will Change Cities at https://www.dezeen.com/2018/05/21/dezeen-drones-documentary-elevation-release/, accessed 31/7/2021.

[3] Ongoing project which aspires to develop a series of new ‘grounds’ for eco-social reflection.

[4] Herder, Johann Gottfried: Outlines of a Philosophy of the History of Man, Bergman Publishers, 1800, p. 233.

[5] As referred by Ford, Thomas H., in Wordsworth and the Poetics of Air, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p. 36.

[6] Gaston Bachelard, Dallas Institute Publications, Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, 1988.

[7] Carrick, Paul J., Medical Ethics in the Ancient World, Georgetown University Press, 2001.

[8] It is also interesting that these kinds of devices also offer the potential for an FPV (first person view) perspective, which might be a thought-provoking take on the project in some future implementation, through the use of an embedded camera that transmits what the flying system ‘sees’.

[9] Alexandra Arènes, Bruno Latour and Jérôme Gaillardet, Giving depth to the surface: An exercise in the Gaia-graphy of critical zones, The Anthropocene Review, 2018, Vol. 5(2) 120–135, p.122.

1 Trackback