Iitate village, located in Fukushima Prefecture, is typical of rural Japanese hamlets. One finds large arable lands buttressed by imposing mountains that dazzle with emerald-green colors. Iitate fits perfectly this postcard image that many tourists have of rural Japan, with just one difference: among the fields of green are over a million and a half vinyl bags filled with radioactive tainted soils. Rows of black plastic bags, piled on top of each other, form Mayan-like pyramids as far as the eyes can see.

Rows of black plastic bags in Iitate. Photo by author.

These bags are the result of a radioactive decontamination project launched by the Japanese state in the aftermath of what is now known as the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Prior to this catastrophe, Fukushima was an obscure region of northeastern Japan. Yet, on March 11, 2011, the name Fukushima became part of history, finding its place alongside the Chernobyl and Three Mile Island of this world.

When I first set foot in Iitate, during the spring of 2016, five years had passed since the disaster. The forced evacuation of citizens was short-lived, since the Japanese state had adopted a policy of repatriation to former restricted areas. The first citizens to willingly return were elderly farmers for whom Iitate was their “native land,” a concept that the Japanese call furusato. This was the experience of Tanaka (pseudonym), a 67-year-old farmer who had returned to Iitate to grow flowers in his greenhouses. As he once explained: “It’s the place where I was born. I always wanted to come back to this place. Seeing the sun rise, seeing the moon at night. Seeing the blueness of the sky of Iitate…” In Japanese, the term furusato is a notion steeped in nostalgic feelings for one’s hometown and I could see that Mr. Tanaka was very happy to be back in his furusato. But, as opposed to Mr. Tanaka, my experience in Fukushima was somehow different. After all, Iitate was not my furusato and while the place had its charms, my stay was also punctuated by the fear of adverse health effects from radiation exposure.

The greenhouse of Tanaka. Photo by author.

Consequently, an important part of my ethnography was molded through my own experience with radioactive hazards. I remember a precise event that later made me more reflective of the researcher’s positionality in studying nuclear disaster.

In the spring of 2016, I was invited to witness the work of an organization in Fukushima, mostly farmers attempting to revitalize the sociocultural life of their region. At 5:30 in the morning, I was shaken out of bed by Masayuki (pseudonym), who needed my help for some renovations at their center. There, we began moving old planks which resulted in propelling a mist of wood particles through the air. The sight of the mist got me worried: “What if I breathe those particles? Are they radioactive? Why didn’t I bring a mask, is it dangerous? What’s the radiation level? Where are my gloves…” As I looked at the dust that covered my clothes, I began to feel edgy and disturbed, becoming a captive of the world of radiation. A similar incident happened when Masayuki filled his gourd with water from a natural source. “If you’re thirsty you can go and drink some water, it’s clean (kirei),” he told me. I was taken aback by this solicitation. Many things were jostling in my mind; was it really safe, how should I interpret the Japanese word kirei, did he use it to mean “fresh” or “uncontaminated?” In the end, I took a small sip of water and began to feel anxious, wondering, “what if?” For his part, Masayuki was gulping down large quantities of water without apparent worries.

A sign indicating the level of radiation in Fukushima. Photo by author.

These experiences made me realize that one cannot constantly live in a state of chronic anxiety for the potential adverse health effects of an invisible harm. It was precisely these kinds of “what if” moments—the impossibility of solidifying a clear state of risk—that were some of the most energy-draining aspects of radiation hazards. In that regard, I noticed that many citizens in the village rarely talked about the potential adverse health effects of radiation. Masayuki and I never discussed health, but instead talked about the nature of Iitate, the name of its plants, or the different shacks that needed fixing. After a few days, I stopped thinking about radiation, as it physically exhausted me.

When I came back from fieldwork, friends, colleagues, and family members asked if I had been scared for my health. Obviously, but I also realized that fear was a luxury that many couldn’t afford. While I was fearful of unnecessary radiation exposure, I ended up writing this piece in the comfort of my house. That experience made me ponder the ethics of ethnography and the difference between being there as an ethnographer and living there as a resident. Thinking about radiation hazards was different for me, a young white male, than for a farmer who treasured land handed down from generations. These experiences made me realize that an ethnographer needs to be careful of bias when producing first-hand accounts of the lives of others. More importantly, they made me realize that not every citizen wants their post-Fukushima life to be depicted via “body-centric damage narratives” (Murphy 2017, 496). For some, there are forms of harm greater than radiation exposure and discourses of victimhood do not help people like Tanaka to go on with their lives.

“Happy Fukushima” sign at the train station. Photo by author.

In that line of thought, many ethnographies of nuclear life are increasingly producing scholarships that precisely move beyond tropes of victimization and damaged biologies. This “post-victimization” approach is gaining a lot of momentum in anthropology. For instance, in an article entitled “The Construction of Risk and the Resilience of Fukushima in the Aftermath of the Nuclear Power Plant Accident,” anthropologist Yoko Ikeda argues that tropes of Fukushima as a nuclear barren land create many hardships for the local population (2013). As she explains:

Everyone I talked to in Fukushima in the summer of 2011 was feeling some kind of stress in thinking about radiation in their everyday lives. Still, many Fukushima residents have been resilient, balancing concerns over radiation with getting on with daily life. Living in Fukushima, I have witnessed all sorts of efforts to restore economic and social health, and to keep agriculture, tourism and other businesses going despite the severe impact of fūhyō higai (‘damage by harmful rumours’). I have much hope that Fukushima will bounce back from the disastrous events of 2011, and it is evident now that the process is already well underway. (2013, 171)

Similarly, in a 2021 commentary for Critical Asian Studies, Ryo Morimoto examines “how the radiation damage-centered discourse was and is still damaging residents, undermining their hopes to return to their lands and reestablish their personal, social, and spiritual ties.” Drawing from Eve Tuck’s notion of “suspending damage,” which goes against “research that intends to document peoples’ pain and brokenness to hold those in power accountable for their oppression” (2009, 409), Morimoto calls for “suspending radiological damage to explore a different ‘Fukushima’ than how it has been imagined and entertained.” In sum, Morimoto’s call refuses to create further representations of victimization, going against the “much-told stories of ‘nuclear victimhood’” which have often emphasized the health damages and uncertainties of living in irradiated environments.

In anthropology, this initial focus on what Morimoto calls “nuclear victimhood” is not particularly surprising. It finds its origin in the “romance of resistance” (Abu-Lughod 1990) that epitomizes ethnographies of disasters, health crises, and environmental catastrophes. Via this focus, there is a tendency to contrast the struggles of victims against the viewpoints of corporate polluters. Following George Marcus this is a form of ethnography that usually shows “the effects of major events and large systems on the everyday life of those usually portrayed as victims […] (1986, 168). The post-victimization turn in nuclear anthropology precisely counters this myopia around victimhood’s discourses. Indeed, it humanizes individual responses and makes anthropologists rethink the notion of victimhood.

At the same, I remain worried about the potential pitfalls associated with this turn, especially as it seems to become one of the main optics through which future nuclear studies are to be conducted. I categorize these pitfalls as two-fold: a move back to cultural relativism and a cooption of this work by state actors and nuclear lobbies.

First, the post-victimization turn is particularly useful in providing a description of life within irradiated environments. It explains why some people decide to remain in Fukushima despite contamination and hardship. It is particularly apt at examining the internal logic of affected individuals, such as how one’s love for their furusato trumps concerns over radiation. This brings a deeper sense of place, much needed in nuclear studies. At the same time, the underscoring of this internal logics should not be done at the expense of an externalized critique from the anthropologist. For instance, following the notion of “urgent ethnography” (Slater 2013), which is a non-judgmental process of collection, archival, and recording of the 3/11 Japanese disasters produced throughout the voices of victims themselves, Ikeda ultimately argues that “people’s sense of risk is relative” and that individuals in Fukushima “decided for themselves where danger ended and safety began” (2013, 170). Refraining from passing judgments on citizens’ choices after this disaster, Ikeda sets both discourses of victimization and non-victimization on a symmetrical plane: risk is relative and so is the sense of victimhood.

In the post-victimization turn, this conceptualization of risk and victimhood as subjective appears highly problematic to me, since it brings anthropology back to cultural relativism, which treats all viewpoints as equal. A potential consequence of this relativism is that anthropologists of nuclear issues will remain uncritical to producing accounts that illuminates the forms of structural harms that bring nuclear disasters in the first place, while making capitalistic-induced catastrophes forgivable in order to let people go on with their lives. However, it is equally important to look at how narratives of victimization, safety, or danger are shaped by larger global systems that influence parts of citizens’ practices and discourses. For example, knowledge about nuclear issues has been deeply influenced by military secrecy, government propaganda, collusion with the energy lobby, scientific controversies, or neoliberal policies, to name but a few. Unfortunately, these broader factors are at play in impeding a politics of victimization after most nuclear disasters. Therefore, it is also the task of nuclear ethnographies to critically examine how these external factors affect one’s agency and discourses about victimization. What affected individuals say and do is not the mere result of their free will (e.g., risk is relative), but something equally molded by displays of power that go far beyond specific events or localities. A relativistic approach within the post-victimization turns risks being blind to such power plays.

Second, the post-victimization turn is already encouraged by states, nuclear lobbies, and regulatory agencies that do not want a politics of victimization to ever happen after nuclear incidents. For example, the Japanese state has first and foremost enacted a politics of revitalization in the years that followed 2011. Unfortunately, this policy has often resulted in a disregard of radiation low-dose adverse health effects, pressures that silence critical voices, the cherry picking of experts in risk communication, informational propaganda, the restart of nuclear power plants, and the cut of financial supports for many evacuees (see Polleri 2020, 2021; Asanuma-Brice 2021). This turn is also supported by nuclear and radiological scientific communities for whom the disaster impeded a nuclear power industry revival known as the “nuclear renaissance” (Gordon 2011). Consequently, many scientific communities have tried to empower people via a normative vision of radiation risk and recovery that disregards victimization (and obviously compensation). What the post-victimization turn can fail to examine is who or what gets actually empowered by these narratives. Often, empowering citizens beyond tropes of victimhood is a means of shifting responsibility for ensuring safe living conditions onto the shoulders of affected citizens (Polleri 2019).

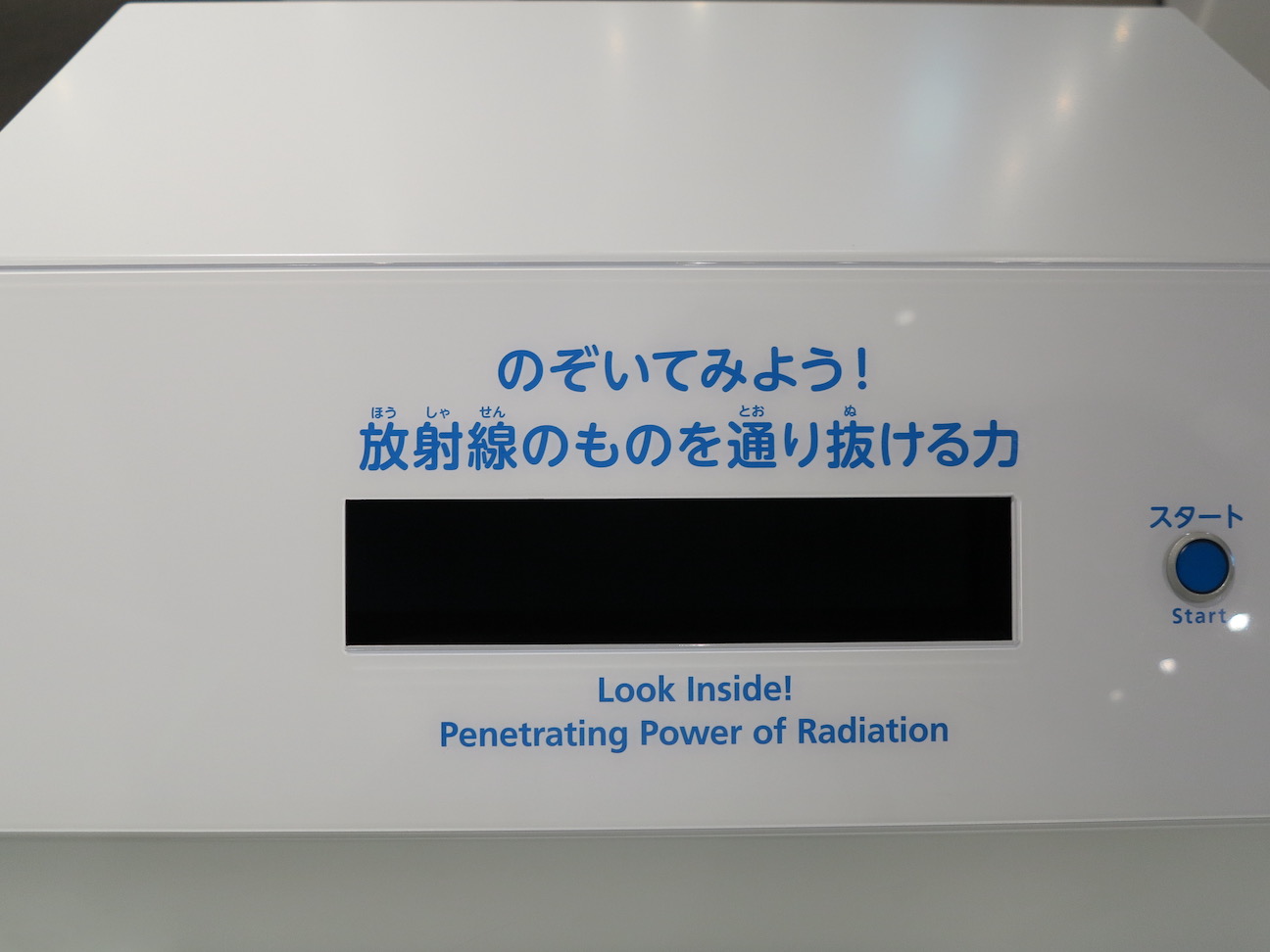

Centers are being created in Japan to help former victims live with radiation. Photo by author.

To be clear the academic approach to this turn is different. For instance, Morimoto warns scholars of not blindly “glorify and justify” lives within residual radiation and Murphy reminds us that “chemical relations are racist, harmful, even deadly […]” (2017: 499). Nonetheless, I do very much agree with David Bond’s recent critique that part of the call for suspending damage-based research seems “to overlap with the deep investments of petrochemical and fossil fuel industry in rendering the real injuries of their operations invisible” (2021: 400). For nuclear studies, this cooption has already started in networks, organizations, workshops, and conferences that promote collaboration between social scientists and nuclear actors. Having participated in some of these collaborative endeavors, I can attest that this “collaboration” is often asymmetrical as it entails nuclear actors cherry-picking social science contributions that best suit their needs. Unfortunately, this post-victimization turns risks becoming highly biased toward a pro-nuclear regime that attempts to reduce so-called irrational fears toward radiation risks, increased public acceptance toward nuclear issues, while reinstating civic resilience to industrial incidents at all cost. While the academic turn to post-victimization brings noteworthy points of intellectual debates, I see this move as a further blow to the independence of the academic community, which is already extremely precarious in the nuclear domain (Boncourt 2020). As an outlook for the future, is the post-victimization turn destined to be coopted and ultimately counterproductive? Or will some academics be able to carefully maneuver it otherwise?

References

Abu-Lughod, Lila. 1990. The Romance of Resistance: Tracing Transformations of Power through Bedouin Women. American Ethnologist. 17(1): 41-55.

Asanuma-Brice, Cécile. 2021. Fukushima, dix ans après. Sociologie d’un désastre. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme.

Boncourt, Thibaud, et al. 2020/1. Que faire des interventions militaires dans le champ académique? Revue d’histoire. 145: 135-150.

Bond, David. 2021. Contamination in Theory and Protest. American Ethnologist. 48(4): 386-403.

Gordon, Julie. 2011. “Nuclear Renaissance could Fizzle after Japan Quake.” Reuters, March 13. Accessed from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-japan-quake-nuclear-analysis/analysis-nuclear-renaissance-could-fizzle-after-japan-quake-idUSTRE72C41W20110314 on March 3, 2020.

Ikeda, Yoko. 2013. The Construction of Risk and the Resilience of Fukushima in the Aftermath of the Nuclear Power Plant Accident. In Japan Copes with Calamity: Ethnographies of the Earthquake, Tsunami and Nuclear Disasters of March 2011, eds. Slater, David H., Brigitte Steger, and Tom Gill, 151-175. Bern: Peter Lang.

Marcus, George E. 1986. Contemporary Problems of Ethnography in the Modern World System. In Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, eds. Clifford, James and George E. Marcus, 168. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Morimoto, Ryo. 2021 “Ethnographic Lettering: ‘Pursed Lips: A Call to Suspend Damage in the Age of Decommissioning’,” criticalasianstudies.org Commentary Board, March 22. https://doi.org/10.52698/ASPR7364.

Murphy, Michelle. 2017. Alterlife and Decolonial Chemical Relations. Cultural Anthropology. 32(4): 494-503.

Polleri, Maxime. 2019. Conflictual Collaboration: Citizen Science and the Governance of Radioactive Contamination after the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster. American Ethnologist. 46(2): 214-226.

Polleri, Maxime. 2020. Post-political Uncertainties: Governing Nuclear Controversies in Post-Fukushima Japan. Social Studies of Science. 50(4): 567-588.

Polleri, Maxime. 2021. Radioactive Performances: Teaching about Radiation after the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster. Anthropological Quarterly. 94(1): 93-123.

Slater, David H. 2013. Urgent Ethnography. In Japan Copes with Calamity: Ethnographies of the Earthquake, Tsunami and Nuclear Disasters of March 2011, eds. Slater, David H., Brigitte Steger, and Tom Gill, 25-49. Bern: Peter Lang.

Tuck, Eve. 2009. Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities. Harvard Educational Review. 79(3): 409-428.