When I landed in Bangalore in early 2020, it was a long-awaited moment of my grad school journey. I had finally defended my proposal and was set to transition into fieldwork in the next couple of months. In my preparation for fieldwork, I had read many ethnographies, most of which had an arrival scene. It seemed that the first couple of weeks of entering a field site presented a crucial lever of juxtaposition for ethnographic writing that lends itself to evocative descriptions of the setting. The “arrival trope” has been long challenged in anthropology through accounts that complicate the narrative of an ethnographer entering an unperturbed native setting (Pratt 1986). Pratt also complicates the artificial distinction between personal narrative and “objective” description, particularly as they are blurred in moments of transition or arrival in ethnographies. For me, the trope of arrival was exciting despite all its problems because it finally gave me an opportunity to re-enter a world that I was familiar with and describe it on my own terms. I had worked as a software engineer before and now wanted to study gender and caste relations in the computing industry. Dalits, formerly seen as “untouchable” under the caste system, and other lower caste people, have been subjects of upper castes doing research for a very long time. I was looking forward to subverting the arrival trope as a Dalit woman doing ethnography where upper castes were my research subjects. I wanted to do this through participant observation in the computing industry that is highly dominated by upper castes.

Here’s an excerpt from the first fieldnote I ever wrote:

Of course, the field can be home for some but then do we ever stop studying it? Not like I have; I am still working on a site called “my past” and draw constant inspiration for my writing from it. (…) Artificial boundaries are overused but underrated. I draw them just to stay sane sometimes, I draw them simply to make sense of a mess sometimes – (I do what they call) “science”.

I was looking forward to my “arrival” in the field with no funding and barely any access. All that I could manage was to work in a technology firm where I hadn’t negotiated field access in the hope that I would build relationships in some organizations in Bangalore for future access. I kept asking myself, “Am I doing fieldwork now? Is this fieldwork? Am I there yet?” All this while a global pandemic was underway and two months later it had finally reached India. All technology firms had shifted their software work remotely as we headed into a lockdown that would last months instead of the initially hopeful estimation of weeks. The question of arrival became ever more complicated because where was I going to arrive anymore? All the sites I wanted to study were now online and in-person interaction was impossible to imagine. Grad school teaches you that fieldwork is about adapting to all kinds of situations, but no one taught me how exactly to keep studying something that was in the flesh yesterday and today, a voice in the cloud.

The cherry on top was a leadership change in the only organization where I had built a decent relationship, which meant I no longer had insider access. I felt cheated of my moment of arrival. I waited and waited for that moment of dramatic entrance when I would take copious fieldnotes, my notebook brimming with characters, scenes, and descriptions. Even something as simple as writing fieldnotes became an exercise in irony; was that Facebook group I was hanging out in, or that call I just had with an engineer on my team fieldwork, or not? When nothing is your field, everything is your field. At the same time, I kept encountering a resounding silence around the question of caste in these spaces. Conversations about diversity and inclusion focused mostly on women in technology and had programs in place for remediating the lack of women in computing. Most communities even spoke of issues of representation related to sexuality or gender more broadly, as well as neurodivergence and disability. They were also slowly discussing regional, class, and language differences. As someone who was trying to study caste, I kept looking for its mention somewhere in explicit terms but was always left wanting. I was constantly uncertain of how I could study caste when no one even talked about it. When nothing is about caste, is everything about caste?

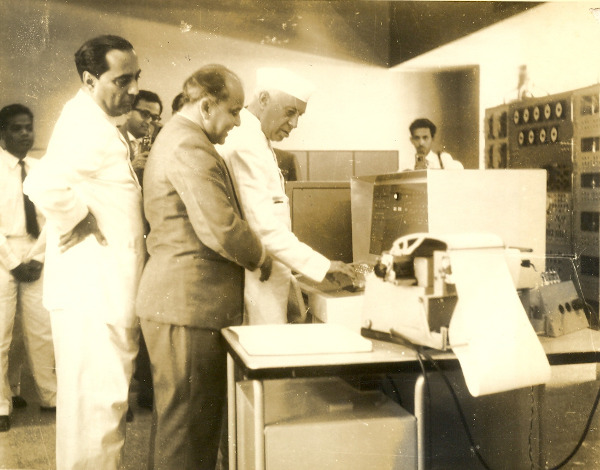

Professor M.S. Narasimhan demonstrating the first Indian digital computer to Jawaharlal Nehru and Homi Bhabha at Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. Image from Wikimedia

So, when I started interviewing Dalit engineers for my research, it was a rather fateful coincidence that they wrestled with a similar uncertainty in their encounters with caste at work. Modern urban Indian society understands itself as moving away from caste. In particular, engineering and computing are seen as bastions of meritocracy and castelessness owing to the narrative of progress, modernity, and innovation. In particular, upper castes see themselves as casteless and meritorious vis-à-vis lower-caste communities that avail equal opportunity benefits through reservations (or affirmative action) (Deshpande 2013; Subramanian 2019). In our upcoming work at CHI2022, my co-authors and I argue that computing is far from casteless by exploring how caste is encountered and negotiated by Dalit engineers and what it tells us about caste as a modern phenomenon[1].

We found that Dalit engineers learn to interpret caste inscriptions, often encoded in the language of meritocracy, to subvert or interrupt them. We discuss these strategies to shed light on the myths of castelessness that have been firmly encoded in the cultural and social discourse of modernity in computing. This involves learning what cues and proxies are code for caste in a culture that vehemently denies its existence while covertly mapping it out. It requires artfulness and practice in interpreting caste hieroglyphics in upper-caste worlds. The process starts early in the form of first encounters with the idea of caste, then develops into a constantly evolving dictionary of surviving and negotiating one’s place in nominally casteless worlds.

Here, I attempt to establish the stakes of the following research question: Why do the strategies of how Dalits encounter and negotiate caste in computing matter? They matter because they make an argument for how traveling, and not arriving, at caste is the mode in which it is understood in casteless worlds. Like me, my Dalit interlocutors seemed to be always traveling in the worlds of computing learning to read caste legibility inscribed in the fabric of castelessness but never really “arriving” at caste. “Was the comment I heard about non-vegetarian food about caste? Was I not invited to a party because of my caste? Was there a moment when I was not successfully passing and gave away my caste?” These are some questions that I believe arise for my interlocutors. This blog post traces Priyam’s story to understand how ambivalence of whether something is about caste is the mode through which most Dalits need to travel in a nominally casteless setting.

I met Priyam through a post on Twitter in early 2021. He responded to my call for Dalit engineers in the computing industry whom I wanted to interview for my study. He is a software engineer in his early thirties working for a multinational technology firm. For Priyam, his first brush with caste was in third grade when a friend was talking about celebrating a Hindu festival. When asked about his plans, Priyam said that his family doesn’t celebrate that festival and he wasn’t aware of it. His friend asked “So what do you celebrate? You’re Hindu right?” Priyam said, “We celebrate Buddh Purnima and other Ambedkar festivals.[2]” His friend looked at his older sister and exclaimed, “(translated) Oh! He is a Scheduled Caste!” His older sister looked nervously at Priyam, who at that point didn’t know what SC meant, and quickly shut her brother up by saying “Ey! You shouldn’t say things like that!”

This very marker of festivals came up again for Priyam when he started working for a multinational technology company as a software developer where he was asked about his Diwali plans. Priyam responded that he doesn’t celebrate Diwali, but unlike the last time, didn’t go into the details of why and what festivals he did celebrate. One of his co-workers remarked, “(translated) I know what kind of festivals he celebrates; he celebrates anti-national festivals….” Although Priyam never revealed his caste identity at work, he was very vocal against casual Islamophobic sentiments. He couldn’t be sure which festivals were seen as anti-national, and was left wondering what his co-worker meant—Islamic or anti-caste festivals? Or both? Did the co-worker know that he was Dalit?

Another time some implicit caste inscriptions made Priyam uncertain if he had met a Dalit person at work. A co-worker remarked that he grew up in a worker’s colony/house [Kamgar Colony]. The word Kamgar in Marathi means janitor, or in Indian parlance, a sanitation worker. This profession has historically been associated with Dalits and even now continues to be primarily made up of lower castes, predominantly Dalits. Priyam was curious if he had correctly interpreted this cue and started following the co-worker on Twitter. Some of his posts were sympathetic to the anti-caste movement or the rights of minorities, but how could Priyam be sure that his co-worker was indeed Dalit? Weeks later, the co-worker shared an article about the life expectancy of sanitation workers (or manual scavengers), which is as low as 40 years. He tweeted a quotation from the article; “(translated) It’s a necessity/compulsion… (we/one) have/has to do it.” This comment made Priyam somewhat confident his co-worker too was Dalit, and he became friendly with him; there was an ease in their conversation unlike those between Priyam and other upper castes at work. But there was no open conversation about caste between them. Did Priyam successfully guess his co-worker’s caste? Did the markers tell the story of caste? Or something else?

In my attempt to arrive at my field site in a pandemic, I have continued to travel in whatever forms of computing worlds I get access to, most of them online. And while I haven’t arrived at a particular site in the way that I expected to, I am traveling through these spaces, picking up the traces of caste wherever I can. I realize that mine is a multi-sited ethnography (Marcus 1995) – I am following people on social media and meetings online, I chase them for interviews on WhatsApp messages and calls, I sit around in meetings about diversity and inclusion on Zoom taking fieldnotes, and I am trying to study something that according to many doesn’t exist in computing. As I am observing the effects of caste relations woven into the social fabrics of computing in the narratives and actions of Dalit engineers, I am also simultaneously trying to understand what caste in communities of upper caste engineers is when they don’t explicitly mention it or believe that it exists.

Writing about the trope of ethnographic arrival, Mary Louise Pratt suggests that this trope may nevertheless be useful in how it can be transformed:

Surely a first step toward such change is to recognize that one’s tropes are neither natural nor, in many cases, native to the discipline. Then it becomes possible, if one wishes, to liberate oneself from them, not by doing away with tropes (which is not possible) but by appropriating and inventing new ones (which is) (Pratt 1986).

My dissertation is mediated by stories of the uncertainty of arrival into the field as much as it is shaped by the uncertainties of making sense of caste legibility—uncertainties that arise both out of my object of study itself, caste in computing worlds, and my process of navigating it as a Dalit woman. My interlocutors’ stories guide me to undo the trope of arrival. Their encounters with caste are as real as they are in their heads. Understanding how Dalits negotiate being in upper-caste worlds of computing is indicative of the uncertainty under which they must continue to be a part of this industry. Dalit engineers in computing are haunted by the ghosts of Manu [3] in mundane everyday sociality at work, but they continue to appropriate and invent new ways of making sense of the landmine of caste legibility. They do this by subverting it and asserting their agency in worlds historically not designed for them.

If arrival is a trope to be appropriated in ethnographic writing, I want to underscore the value of traveling over arriving – more so for studying intangible things that “don’t exist” than those that do. In my fieldwork, I am traveling the terrains of computing collecting traces across sites, spaces, places, corners, platforms, never entirely sure if what I am observing is about caste but trying to read for it against the grain of castelessness. While my Dalit interlocutors continue to travel through computing cultures seldom do they arrive at a resolution of the question of caste. They, like me, continue to travel but never arrive; they occupy and navigate, and therein lies the art of knowing anything and everything there is to know about doing an ethnography of caste in computing.

Footnotes

[1] The pre-print of the paper is available here and it will be soon published on ACM digital library with open access.

[2] Dr. BR Ambedkar was a legal, economic, and anthropological scholar and an anti-caste leader whose dedicated representation of the issues of marginalized communities and his motion for the annihilation of caste (Ambedkar 1971), have made him one of the most revered figures across India. The followers of Ambedkar call themselves Ambedkarites, many of whom have followed his footsteps in resisting the Hindu caste system by converting to Buddhism (Bellwinkel-Schempp 2007). Most of this community celebrates Buddha Purnima (Lord Buddha’s birthday) and Ambedkar Jayanti (Ambedkar’s birthday).

[3] Manu is the author of the book Manusmriti which establishes the varnashrama dharma, i.e. the hierarchy of caste within Hinduism in the form of four varnas or caste categories which outlines guidelines for the purpose and role of each caste in the hierarchy. The system places Shudras at the bottom of the caste pyramid and untouchables (or Dalits) and adivasis (or indigenous tribes) outside of the caste system as they are inferior to all other castes.

Bibliography

Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. 1971. Annihilation of Caste with a Reply to Mahatma Gandhi. Bheem Patrika Publications Jullundur City.

Bellwinkel-Schempp, Maren. 2007. “From Bhakti to Buddhism: Ravidas and Ambedkar.” Economic and Political Weekly, 2177–83.

Deshpande, Satish. 2013. “Caste and Castelessness: Towards a Biography of the ‘General Category’.” Economic and Political Weekly, 32–39.

Marcus, George E. 1995. “Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (1): 95–117.

Pratt, Mary Louise. 1986. “Fieldwork in Common Places.” Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. University of California Press.

Subramanian, Ajantha. 2019. The Caste of Merit: Engineering Education in India. Harvard University Press.

1 Comment

Great post. Really like the poetic prose that instills the idea of movement (travelling) that is key to the idea being conveyed. Would love to read more