People who have abortions are often thought of as inherently vulnerable. When retold without nuance, this narrative can be harmful to abortion-seekers, as well as to reproductive autonomy more broadly, since it reinforces negative stereotypes about abortion and abortion-seekers. Changing affective paradigms around abortion has been a key concern for feminist activists around the world. In fact, a significant part of my ongoing PhD research on pharmaceutical abortion, healthcare access, and feminist activism in Argentina is concerned with how and why feminist activists seek to disrupt the social perception of abortion as intrinsically being a certain kind of experience—tragic, shameful, vulnerable, to give just a few pointers. While preparing for my data collection, I was struck by the discrepancy between how feminist activists who accompany abortions conceptualise the agency of (potentially) vulnerable abortion-seekers and my UK university’s research ethics committee’s approach to it. Especially given my own positionality as a non-Argentine PhD student, this prompted me to reflect on the challenges of navigating this divide when researching feminist activism and self-managed abortion. To this end, I unpack some of my reflections while trying to balance my duty of care for potentially vulnerable participants with respect for their agency. Striking this balance can be especially complicated when the understandings of both risk and ethical practice diverge between ethics committees, who—to a certain extent have to—adopt a universalist approach, and feminist practitioners holding contextually specific expertise on the subject, while also frequently working with different definitions of care. This divergence is even more pertinent in the case of abortion, an experience steeped in assumptions based on moralised and medicalised social and political discourses. Throughout my research process, I have understood refusing to reproduce such paternalistic discourses as essential to doing ethical research, alongside attending to potential vulnerabilities.

I came to reflect on these dynamics over the course of my doctoral research on self-managed abortion and feminist activist and epistemic practices in Argentina. Activism facilitating and accompanying safe, self-managed abortion through the use of abortifacient pharmaceuticals has a long history in Latin America. In fact, it was Brazilian feminist activists who first noticed the abortive side effects of misoprostol, a pharmaceutical that is today routinely used for the termination of pregnancy around the world, back in the 1980s, and developed a regime for its safe and effective use (De Zordo, 2016). In Argentina, feminist groups sharing information about self-managed, pharmaceutical abortion have been active since at least 2009, when the collective Lesbianas y Feministas por la Descriminalización del Aborto started operating a phone line (Drovetta, 2015) and soon after published a manual titled “All you want to know about how to have an abortion with pills” (2010). In 2012, Socorristas en Red, a national network of abortion companions, was formed by members of the National Campaign for the Right to Legal, Safe, and Free Abortion, providing not only information, but also support throughout people’s abortion journey (Vacarezza, 2023). By 2015, Socorristas en Red had become the most prominent network accompanying abortions across the country (McReynolds-Pérez, 2017).

At the heart of their activism has been the organisation of group meetings with people seeking to have an abortion. During those meetings, activists share all the information abortion-seekers need in order to have a safe, self-managed, feminist-accompanied abortion outside the healthcare system (Zurbriggen et al., 2017). This accompaniment of abortion constitutes a form of feminist community-based healthcare (Keefe-Oates, 2021) that has remained important after the legalisation of abortion in 2020, which permits abortion on all grounds, including self-managed procedures, until the fourteenth week of pregnancy. This practice of (health) care is underpinned by a set of feminist convictions. Most importantly, abortion is not thought of as an inherently vulnerable moment and activists understand there to be strength in sharing one’s situation and experiencing abortion collectively. This is not to deny the precarious situation abortion-seekers may find themselves in, but rather to recognise that vulnerability arises from social and structural stigmatisation, not the experience of abortion itself. Similarly, prior to legalisation, activists located the risk of a self-managed abortion not in the practice alone, but rather “insist on contextualising the technical risks of misoprostol within the social situation of illegal abortion” (McReynolds-Pérez, 2014: 163). In fact, the infantilisation of pregnant people and the denial of their agency significantly contributes to upholding stigmatising social and political structures that inhibit reproductive autonomy. In opposition to this, activist groups like Socorristas en Red affirm that the person seeking to terminate their pregnancy has the agency to make their own, informed decisions.

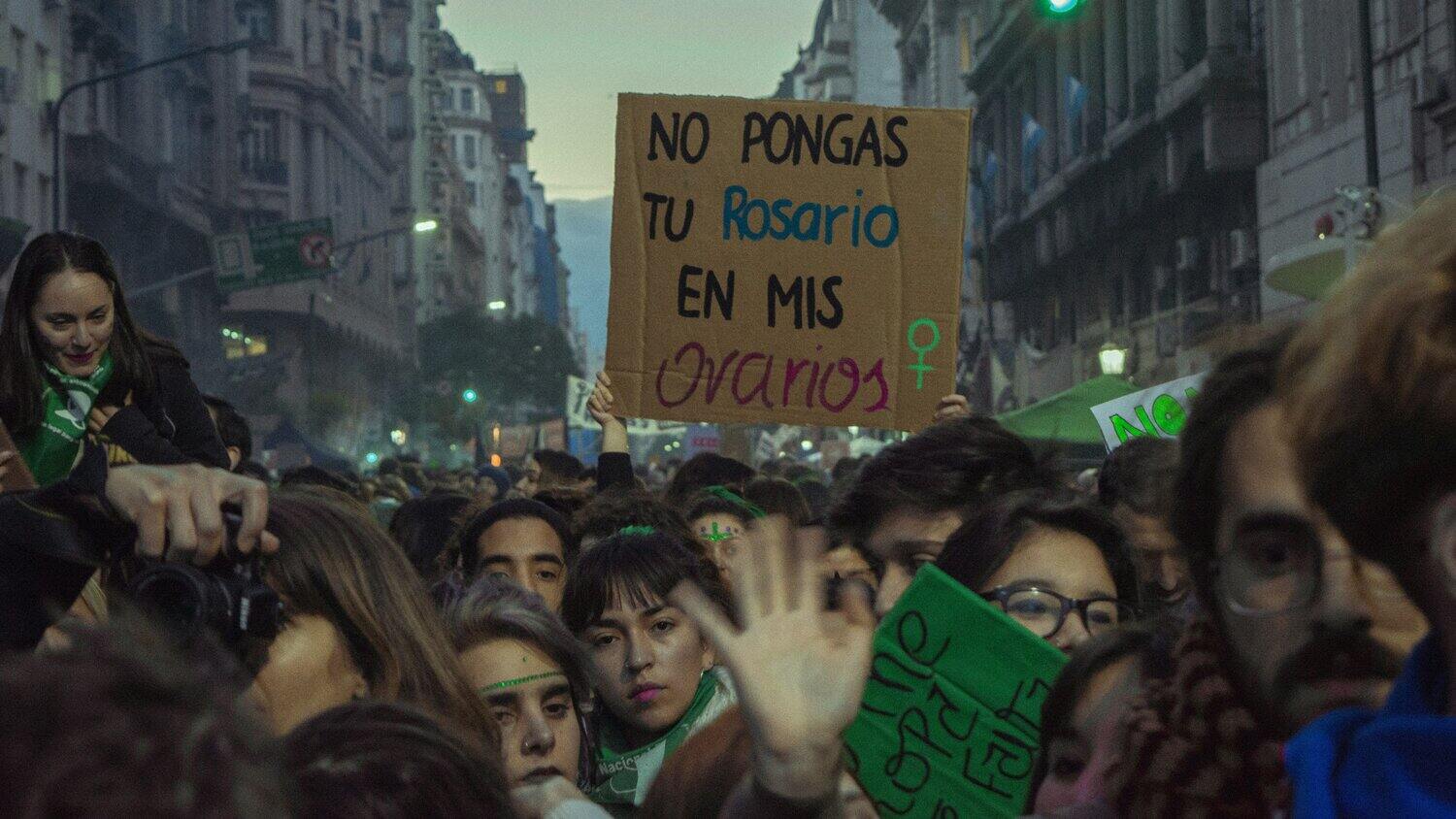

Image of people on the street at night by Matias Hernan Becerrica (via Unsplash)

Further, it is important to highlight that in a context where abortion is legal, choosing to be accompanied by Socorristas en Red is a decision for a particular kind of abortion experience, one that is feminist, collective, and opposing the silence and stigma abortion is shrouded in. This understanding of abortion stands in stark contrast to the way in which abortion is commonly conceptualised in medical and political discourse, as well as popular culture—as a private and necessarily difficult experience overseen by a medical professional. So when I, following the invitation of members of an activist group that accompanies abortions to attend some of their meetings with abortion seekers, applied for approval from my ethics committee to observe these meetings, I was only partially surprised by the very different understandings of abortion and vulnerability that underpinned the committee’s response. In contrast to feminist efforts to normalise abortion as yet another obstetric event, these reflected a perception of abortion as an always regrettable and emotionally challenging experience.

Likely exacerbated by the United States’ overturning of Roe v. Wade a few months prior, the ethics’ committee’s comments and requests for clarification showed a strong focus on criminalisation and an underlying assumption that being known to be ‘involved with’ abortion was inherently risky. This perspective foregrounds developments in the Global North, where abortion rights have been under threat not only in the US, but also in Poland, and more recently in the UK. Applying these developments to Latin America, where abortion politics have been developing very differently, presupposes the upsurge in particular modes of criminalisation—for instance the increasing surveillance of self-management—to be universally applicable and reinforces paternalistic conceptions of abortion-seekers as a group with compromised capacity to make self-determined decisions. It ignores the particular histories of feminist activist efforts to change social perceptions of abortion—in the case of Argentina for more than thirty years—as well as recent legislative victories in Ecuador, Mexico, Argentina, and Colombia (Vacarezza, 2023). This mirrors a frequently taken approach to sexual and reproductive health, which take women and other people with the capacity to gestate as unable to take charge of and live autonomous (sexual and reproductive) lives. Examples of this include women being denied tubal ligation, sometimes without a partner’s consent or simply for being too young, as well as legally mandated consultations and reflection periods prior to being able to obtain an abortion through a healthcare provider.

Within research ethics, vulnerability can be defined as being “especially prone to harm or exploitation” (Lange et al., 2013: 333). However, the authors also highlight that it is a difficult-to-define concept that often escapes definitional clarity. Rather, it is necessary to understand vulnerability as context specific and dependent on a variety of factors, meaning that there is a tension between acknowledging structural vulnerabilities and individual experiences. In the case of abortion, especially abortion that takes place outside of state-sanctioned institutions, generalising abortion-seekers’ experiences is particularly problematic as ethics committee’s own biases may play into how this demographic is perceived or defined in the first place. Abortion exceptionalism describes the idea that abortion requires “more intensive […] scrutiny […] because it is perceived as so controversial and politically sensitive” (Smyth, 2023: 8), which I borrow from Smyth’s application of it to international law. It provides a useful framework for understanding that the assumption that women’s ability to give informed consent is automatically reduced by the supposedly necessarily distressing situation of abortion reifies gendered narratives of agency and vulnerability. In turn, it disenfranchise all people who may become pregnant.

A more conducive way to think about vulnerability and agency may be an intersectional model of structural vulnerabilities as put forth by Khirikoekkong and colleagues (2020), attending to political, economic, social, and health vulnerabilities. Findings from their study of migrant women on the Thai-Myanmar border highlight that, despite being subject to complex vulnerabilities, these women continue to exercise their agency both in their day-to-day lives and when deciding whether to participate in a research project. In the case of abortion-seekers in Argentina, relevant contextual factors to consider include potential research participants often already having to resolve a host of administrative and sometimes emotional challenges—how do I get time off work? Who can take care of my children while I have the abortion? Where do I find a quiet space to do it? Activists I interviewed told me that, in order to attend the workshop, participants often had to travel significant distances and those with small children might only have childcare for a limited amount of time. When discussing my potential attendance at such workshops, activists therefore suggested that the most appropriate way for me to obtain informed consent would be to ask participants for verbal consent after briefly introducing myself, explaining my research project and attendees’ potential role in it and highlighting that I would leave the workshop should anyone feel uncomfortable with my presence. This would allow attendees to maintain a degree of anonymity towards me and would minimise the time and space taken up by me at an often already stressful moment in their lives. This, of course, is in conflict with many of the consent procedures preferred by academic ethics committees, including several days of reflection time prior to deciding whether to participate or not, as well as the preference for written consent in the form of signed consent forms.

Given the fact that I am carrying out a research project about feminist knowledge production and expertise, it was important to engage with feminist activists as authors of expert knowledge not only theoretically, but also in practical terms. This, for me, also implies relying on their experience and expertise when judging how to adequately obtain consent from participants. My reflections are by no means intended to be an argument against safeguarding research participants. There is a risk of real and significant harm for people participating in research projects, and this is no attempt to negate that risk. Rather, I seek to highlight that in some cases, understandings of what that means to ethics committees and feminist experts may diverge. While activists were very happy to invite me to attend the workshops, a key criterion for them was to ensure participants’ anonymity, meaning I would attend without collecting any identifiable data. Even though activists have long been working towards what has been termed “social decriminalisation of abortion” (Gutiérrez in Vacarezza, 2023: 315)—the breaking of stigma and silence—they also recognise that in the current sociopolitical climate, protecting the anonymity of abortion-seekers is an important part of their duty of care towards them. However, this is directly opposite to the idea of a signed consent form as the ‘gold standard’ of informed consent. Whilst it was ultimately agreed that I could obtain oral consent, this disagreement about best practice leads me to broader questions—who do we suppose to be in need of care, and who is in the position to safeguard whom, and from whom? Who has the authority to determine so?

As a feminist researcher, I have found it at times difficult to navigate the complex nexus of agency and vulnerability. Ultimately, for me, doing feminist research means centring the particular circumstances of my research site and foregrounding the voices of those who draw their expertise from their life and work when determining methodological, ethical, and conceptual approaches. To ethically engage with my research means denaturalising the power imbalances between Global North institutions and activist groups from the Global South that shape the conditions of this research, and placing different emphases— for instance, by crediting expertise to those who draw on their activist and professional practices, rather than relying on academic and institutional titles. Especially when navigating the power imbalance between Global North institutions and activist groups from the Global South as a PhD student from the Global North, I believe it is necessary to question the underlying assumptions that inform research ethics committees’ decisions and keep asking who their guidelines ultimately seek to protect. There is much need and scope for change in institutional research ethics, but my faith in such change is limited. For the time being, I think it is my responsibility as a feminist researcher to account for and ethically respond to the inherent contingency of vulnerability and my, as well as research participants’ and ethics committees’ understandings of it.

This post was curated by Contributing Editor Kim Fernandes.

References

De Zordo, S., 2016. The biomedicalisation of illegal abortion: the double life of misoprostol in Brazil. História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, [online] 23, pp.19-36.

Drovetta, R.I., 2015. Safe abortion information hotlines: An effective strategy for increasing women’s access to safe abortions in Latin America. Reproductive Health Matters, [online] 23(45), pp. 47–57.

Keefe-Oates, B., 2021. “Transforming Abortion Access Through Feminist Community-Based Healthcare and Activism — A Case Study of Socorristas en Red in Argentina” in Sutton, B., and Vacarezza, N. L. Abortion and Democracy: Contentious Body Politics in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group.

Khirikoekkong, N., Jatupornpimol, N., Nosten, S., Asarath, S., Hanboonkunupakarn, B., McGready, R., Nosten, F., et al., 2020. Research Ethics in Context: Understanding the Vulnerabilities, Agency and Resourcefulness of Research Participants Living Along the Thai–Myanmar Border. International health, 12, no. 6: 551–559.

Lange, M. M., Rogers, W., and Dodds, S., 2013. Vulnerability in Research Ethics: a Way Forward. Bioethics 27, no. 6: 333–340.

Lesbianas y Feministas por la Descriminalización del Aborto (eds.), 2010. Todo lo que querés saber sobre cómo hacerse un aborto con pastillas. Buenos Aires: El Colectivo.

McReynolds-Perez, J. et al., 2014. Misoprostol for the Masses: The Activist-Led Proliferation of Pharmaceutical Abortion in Argentina. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

McReynolds-Pérez, J., 2017. No doctors required: Lay activist expertise and pharmaceutical abortion in Argentina. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 42(2), pp.349-375.

Smyth, R., 2023. Abortion in International Human Rights Law: Missed Opportunities in Manuela v El Salvador. Feminist Legal Studies.

Vacarezza, N. L., 2023. Abortion Rights in Uruguay, Chile, and Argentina: Movements Shaping Legal and Policy Change. Southwestern Journal of International Law, 29, pp. 309-347.

Zurbriggen, R., Keefe-Oates, B. & Gerdts, C., 2017. Accompaniment of second-trimester abortions: the model of the feminist Socorrista network of Argentina. Contraception (Stoneham), [online] 97(2), pp. 108–115.