A recent trend in the sciences is the attempt to create inclusive research spaces, as evidenced by the formation of new diversity, equity, and inclusion (hereafter, DEI) initiatives, guidelines, and hiring practices. Archaeology, a field science that has long grappled with discriminatory, dangerous, and exclusionary research conditions, has also made strides to create safe and equitable spaces. However, the very epistemic foundations and practices of the discipline are yet to reflect the orientation toward inclusion. In today’s archaeology, the concepts of “data,” “methodology,” and “rigor” (among others), which form the bedrock of scientific endeavor, still reproduce the dominant Western views of science that at their core are fundamentally heteronormative. Those theoretical approaches in archaeology that are directly concerned with minority identities, values, and politics (e.g. Critical Race Theory, feminist theory, Indigenous studies) continue to be marginalized. The marginalization of these theoretical approaches is an unfortunate development because many of these works challenge the epistemic core of what we do as researchers. They have the potential to transform what we think of as good research, not just what this research produces.

Queer Archaeology

If we are going to make archaeology, and other sciences, truly inclusive, DEI initiatives require reconceptualizing what science is, not just changing hiring and recruiting practices. To truly create inclusive research spaces, we must be accepting of both diverse bodies and diverse ideas. In other words, while DEI initiatives often pitch their goals as being welcoming to diverse, including queer, researchers, there is still a general disregard for the unique theoretical contributions that can be made by queer (and other minority) individuals in the sciences, that is, queer ideas.

My distinction between queer bodies and queer ideas draws on Sandra Harding’s concept of standpoint theory, which has become the basis for many identity-based epistemologies (1986). According to standpoint theory, the knowledge we have and produce about the world is influenced by our social position. Standpoint theory provides a good starting point for understanding what queer epistemology is. Like standpoint theory and Haraway’s (1988) “situated knowledges,” queer epistemology is founded on the principle that queer-identifying people have a unique outlook on life because of their marginalized position in society. Queer theory is inherently post-humanist, emphasizing positionalities that anyone can pick up who feels marginalized in their society (Sullivan 2003). This means that “queer” in the sense of queer theory is not an essentialized identity category but is rather a temporary identity one takes up for political reasons – to confront a power structure. While not all queer people occupy the same standpoint (because “queer” as a political rather than essentialized identity lacks affective certainty), queer archaeologists ask different questions about the past, notice different elements of the archaeological record, and ultimately draw different conclusions because of their queerness.

Although queer researchers look at their data in a queer way, their ability to generate and push forward queer ideas varies due to the differences in affective positions and the fact that many queer ways of thinking tend to be “trained out” of queer researchers. While queer researchers are increasingly being welcomed into the field, they are often permitted to do so with the caveat that they adopt the hegemonic heteronormative methods and theories of the dominant forms of archaeology practiced today.

An archaeological excavation with many bodies. Photo by the author

Archaeology occupies a fruitful, and yet uneasy, epistemological space between the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. This middle position has allowed archaeologists to draw upon wide-ranging disciplinary knowledges to produce richer interpretations. At the same time, it has also caused much debate over the nature of archaeology and the proper role of method and theory. For example, Jones (2001) argues that there are “two cultures” in archaeology. He states that archaeological scientists and interpretive archaeologists are not talking to each other; these two groups have formulated nearly incompatible versions of what the constitutive goals of archaeology are or should be. Of these two cultures, queer archaeology usually sits on the interpretive side.

Queer theory entered archaeology in 2000 with the publication of Thomas Dowson’s article “Why queer archaeology: an introduction.” In this article, Dowson (2000) argues that we need to challenge the heteronormative foundations of archaeology, such as the assumption that everyone in the past was heterosexual or that the nuclear family is “natural” or “desirable” for all peoples. Since then, archaeologists have applied queer theory to several different contexts, in most geographic and temporal contexts. However, while queer archaeology is slowly building momentum, it still occupies a marginalized and siloed space in archaeological research.

I have examined the “status” of queer theory in archaeology to better understand how it has been perceived and implemented in archaeological research. In what follows, I discuss the results of a study I conducted to assess the overall status of queer theorizing in archaeological knowledge production and, more broadly, to better understand what a queer philosophy of science, in archaeology, would ultimately entail.

Researching Queer Archaeology: Methods and Findings

The data I discuss in this post comes from a quantitative survey distributed to archaeologists who have published, currently publish, or plan to publish in the future as part of my current dissertation research. The survey asked approximately 40 questions related to issues of demography, perceptions of science (scientific realism, the role of sociopolitical values in science, where archaeology is situated amongst the natural and social sciences, etc.), and queer archaeology, more specifically.

The data from the survey preliminarily highlights a broad disconnect between the acceptance of queer theory and an understanding of what queer archaeology strives to do. Let us take a closer look.

On the one hand, there is general agreement that queer theory has had either a neutral or positive impact on archaeology. Overall, 65.02% of respondents had a positive perception of queer theory’s impact on archaeology while 55.56% of participants had a “moderate” perception of queer theory. This demonstrates that many archaeologists, at least those who took the survey, have a moderate to a positive perception of queer theory in archaeology.

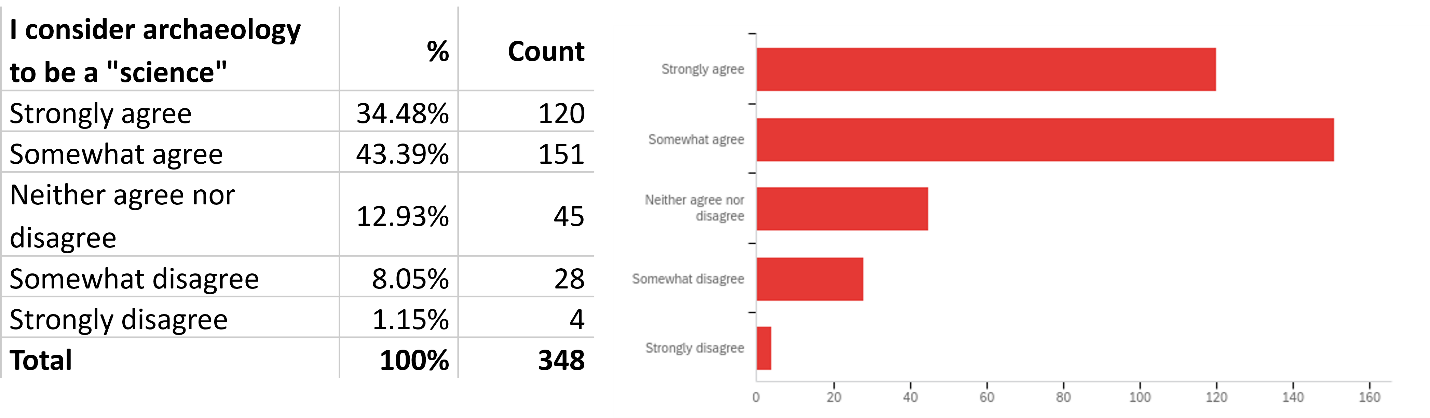

Results of the Qualtrics question asking participants whether they believe that archaeology should be considered a “science”.

These results are fascinating when considered alongside how the survey respondents perceived the nature of science itself. When asked “Is archaeology a science?”, 77.87% said they either “strongly agreed” or “somewhat agreed” (see figure above).

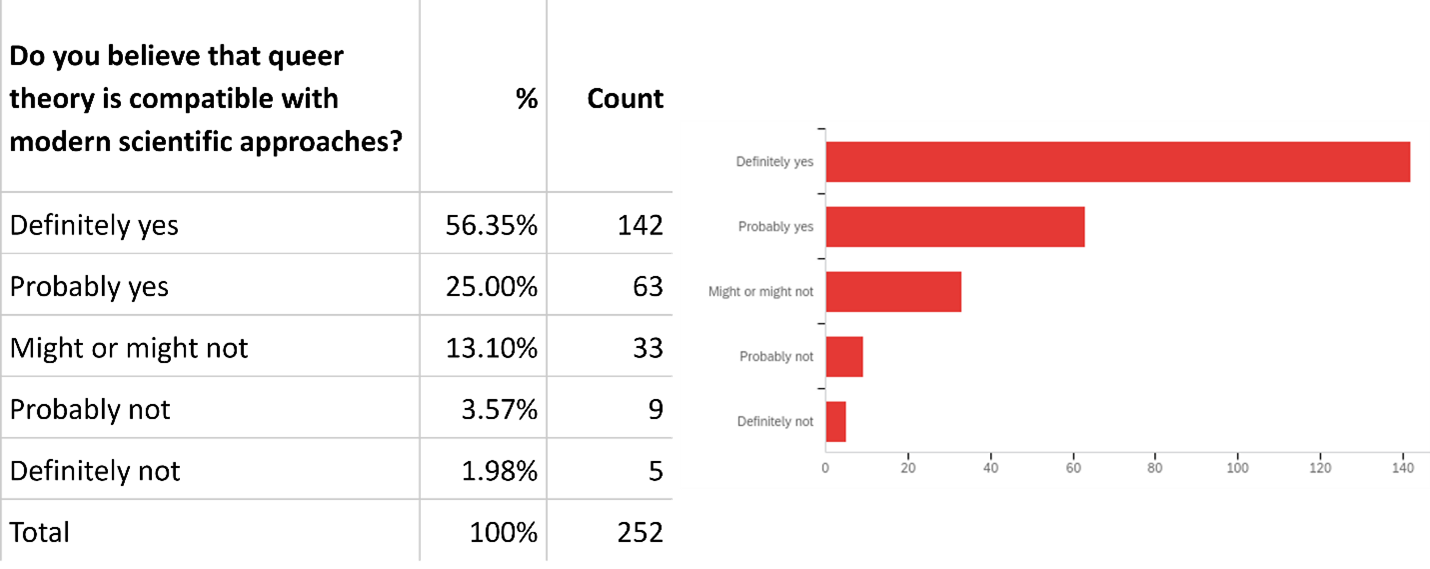

Results of the Qualtrics question asking participants whether they believe that queer theory is compatible with modern scientific approaches.

Similarly, 81.35% of the respondents stated that they “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed that queer theory is compatible with modern scientific approaches (see figure above).

These results did not match my expectations when I began this research. Respondents to the survey find congruity and continuity between the major epistemic tenants of queer theory and Western empirical science, which, as I indicated earlier, is based on profoundly heteronormative masculinist principles.

“Science,” at least in its modern, Western conception, is inherently foundationalist and stable. Each scientific discipline, including archaeology, has a clear and defined method. Undergraduate archaeology students take methods courses, read methods textbooks, and participate in field schools. The goals of these pedagogical activities are to teach burgeoning archaeologists the appropriate methods. The iterated goal is that we want archaeologists who will do archaeology “right”; the unspoken consequence is that this creates a normative and homogeneous methodology.

In contrast, as illustrated briefly above, queer theory celebrates creativity and rejects foundationalism. It is perhaps more in line with Feyerabend’s (1975) “anything goes” attitude toward scientific research. For example, queer archaeologists have rejected archaeology’s over-focus on fertility and reproduction (Chilton 2008) or on building chronologies (Croucher 2005). Therefore, it appears that there is a discrepancy between mainstream academic understandings of “science” and queer ways of producing knowledge.

To help explain this discrepancy – and answer the question of why archaeologists have a positive perception of both archeological sciences and queer theory – I asked respondents to rate their familiarity with queer theory. The data revealed that, in general, archaeologists have low familiarity with queer theory outside of archaeology — the average score was a 4.18 out of a 10 (with 10 indicating “expert” knowledge). When asked about their familiarity with queer theory in archaeology specifically, the mean was only slightly higher at 4.97. These differences are statistically significant, although both are low. Therefore, the data suggest that archaeologists have low familiarity with queer theory as theorized both in and outside of archaeology. However, archaeologists are slightly more familiar with the uses of queer theory in archaeology than they are with the work of queer theorists working outside of archaeology (such as those working in the humanities).

The preliminary data from this survey suggest that there is an epistemic problem in archaeology (and likely the natural and social sciences more broadly). My initial interpretations of the data have exposed a problem in how we approach diverse researchers and ideas. There seems to be an understanding that a generic approval or acceptance of queer bodies and “queer theory” is enough to increase the diversity of the field. However, it is this attitude that has limited the emancipatory and transformative powers of these newer and radical epistemic approaches. Researchers cannot be separated from the unique perspectives, ideas, and theoretical approaches that they bring to their research due to their unique place in society.

The preliminary data from my research highlights the continued acceptance of queer bodies into archaeology (although the discipline has a long way to go, as suggested by the fact that 89% of respondents were cisgender) but not a true reckoning of the contributions of queer theory by queer scholars. What the data currently suggest, and which will be guiding my research questions as I move into the qualitative interviews, are two things:

Image Credit/queerarcheology.com

(1) There is not enough training and education in recently developed, diverse, and explicitly sociopolitically-driven theories. This is an obvious problem outside of the academy, as evidenced by the false war on Critical Race Theory. This problem also seems to impact those inside universities as well.

(2) More importantly, this demonstrates that many archaeologists hold a false binary between minds and bodies. Archaeologists seem to be celebrating diversity in terms of recruiting, admitting, and hiring queer people. However, in the community, there is still little reflection on the relationship between DEI and the epistemic core of the discipline. This is predicated on a misunderstanding of the role that social identity, as an embodied way of being in the world, plays in epistemology and the knowledge-gathering practice, as argued by feminist philosophers of science (see Alcoff 2001; Anderson 1995; Haraway 1988; Harding 1986, 1995; Intemann 2010; Lloyd 1995) and queer epistemologists (as most clearly evidence by Hall 2017). In doing so, archaeologists are not trying to be nefarious in their methods and theories. However, it does demonstrate how a lack of engagement with diverse theories and epistemologies, not just queer theory but also Critical Race Theory, Indigenous studies, and feminism, can diminish long-term positive changes to equity and inclusion in archaeology.

In sum, diversity is not just about who we accept as researchers; diversity and equity are inherently issues of epistemology. This research shows that, at least in archaeology, we have lengths to go before we truly incorporate epistemology and theory into our DEI initiatives, and truly examine the potential of how these can change research in exciting and positive ways.

References

Alcoff, Linda

2001 On Judging Epistemic Credibility: Is Social Identity Relevant? Philosophic Exchange 29(1):1-22.

Anderson, Elizabeth

1995 Knowledge, Human Interests, and Objectivity in Feminist Epistemology. Philosophical Topics 23:27–58.

Chilton, Elizabeth

2008 Queer archaeology, mathematical modeling, and the peopling of the Americas. Paper presented at the Northeastern Anthropological Association, 48th Annual Meeting, March 7-9, 2008. Symposium: The Sex Life of Things: Archaeologies of Sex, Sexuality, and Gender” organized by Katie Dambach and Elizabeth S. Chilton.

Croucher, Karina

2005 Queerying Near Eastern Archaeology. World Archaeology 37(4):610-620.

Dowson, Thomas

2000 Why queer archaeology: an introduction. World Archaeology 32(2):161-165.

Feyerabend, Paul

1975 Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Hall, Kim Q.

2017 Queer epistemology and epistemic injustice. In The Routledge handbook of epistemic injustice, pp. 158-166. Routledge.

Haraway, Donna

1988 Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies 14(3):575-599.

Harding, Sandra

1986 The Science Question in Feminism. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

1995 Strong Objectivity. A Response to the New Objectivity Question. Synthese, 104(3):331-349.

Intemann, Kristen

2010 25 Years of Feminist Empiricism and Standpoint Theory: Where Are We Now? Hypatia 25(4):778–796.

Jones, Andrew M.

2001 Archaeological Theory and Scientific Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Lloyd, Elizabeth

1995 Objectivity and the Double Standard for Feminist Epistemologies”, Synthese 104:351–381.

Sullivan, Nikki

2003 A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. New York University Press, New York.