Farming Fantasies

“There will come a day,” proclaims the player character’s grandfather in the popular video game Stardew Valley, “when you feel crushed by the burden of modern life . . . and your bright spirit will fade before a growing emptiness.” Several centuries before the game’s release, 17th-century English radical Gerrard Winstanley explained that the English peasant “looks upon himself as imperfect, and so is dejected in his spirit, and looks upon his fellow Creature of his own Image, as a Lord above him.” Winstanley and Grandpa propose similar solutions: farming. Modernity is the “thieving power” of the landlord and the insipid consumerism of Stardew’s Joja Corporation—an obvious Amazon analog, down to the eerie smile in its logo and the resigned but-the-prices-are-so-low loyalty its uneasy customers display. The farm, by contrast, is a place for spiritual regeneration via hard work. Grandpa sends you there to grow crops and tend animals, while Winstanley’s Digger movement began cultivating land together.

It would be easy to see Stardew and the “cozy farming game” boom as pastoral romanticism. The Farm haunts America. The Farm is a happy place: the cows go moo, the pigs go oink, the family works hard to provide our food, and the sun smiles down upon it all. Unions, the Environmental Protection Agency, Indigenous activists, and vast reservoirs of feces do not appear. America’s love of The Farm is a misplaced expression of discontent with industrial modernity. It also endorses the violent dispossession American farming was built on and elevates agricultural capitalists as “farmers” by perversely attributing to them the hard work done by disproportionately insecure, wildly underpaid, and exploited workers.

Threatening the bonanza of subsidies for massive landowners that comes in the yearly federal “Farm Bill” is about as politically palatable in America as proposing a monarchy. Children learn about farm animal sounds at such an early age that they seem as fundamental as the alphabet; these lessons do not include the agonized screams of factory farming’s slaughterhouses. We are committed enough to keeping adults from hearing them that “ag gag” laws protect the public from having to see what they’re eating—these laws make it illegal to record the day-to-day operations of American animal agriculture without owner consent. “The Farm” is a saccharine settler colonialist homestead fantasy that legitimizes an industrial production process as dystopian as any. Perhaps the American gamer wants this too.

Constructing the Commons

But deep in America’s cultural history, and Stardew Valley’s appeal, lives another image of agriculture—the public commons. Late medieval and early-early modern English peasants had a series of “common” rights in the lands they lived on: the right to grow crops, fish, gather fuel, and pasture animals. These rights were not transferable by sale. While land was ruled by manorial lords, it was not owned in the sense it is today. “The commons” was far from utopian, but it provided a level of security and dignity to peasants. It was violently crushed in a centuries-long process known as enclosure. From the 16th to the early 19th century, elites carved England up into private plots, often for more profitable animal agriculture, forcing countless commoners into poverty and urban wage labor. They fought back—there was a reason this took centuries. Anti-enclosure riots seeking to preserve the commons menaced elites throughout this period.

The fight for the commons was not always backward-looking either. During the English Civil War, radical commoners demanded something more than a return to what their parents and grandparents had. Winstanley and his “Digger” movement dreamed of a world of common property, an earth shared with its people. They warned in 1649 that “your Laws shall not reach to oppress us any longer, unless you by your Laws will shed the innocent blood that runs in our veins.” Their oppressors chose to do exactly that. The Commons was replaced with The Farm, a private profit generator built on the commodification of the earth itself.

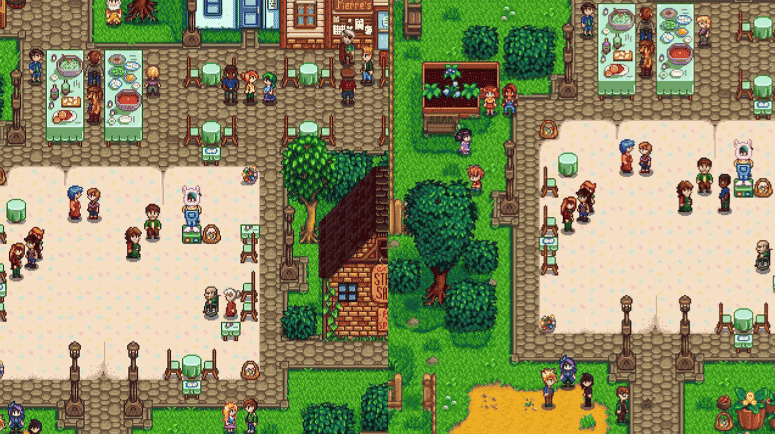

Stardew’s private farm might seem like one of them, as a privately-owned plot of land where you grow goods for the market. But players do not purely put it to private or market use. The game’s colorful cast of characters—like troubled bus driver Pam, friendly blacksmith Clint, and diligent carpenter Robin—come by frequently asking for help. Requests on the town bulletin board offer more opportunities to provide for their needs as they provide for yours. Stardew Valley’s central plot concerns the restoration of the town community center, which requires players to prioritize a diverse array of crops and activities rather than profit maximization. Stardew players are not restricted to their own land either: an entire subcategory of activities consists of foraging and fishing, just as in the commons. While your farm is not a commons, your village is something like it.

Stardew Valley’s “Egg Festival.”

Even the production process looks different from capitalist profit-seeking. Many Stardew players take great pride in maximizing its financial returns—me included. This might seem merely a fantasy of a fair capitalism, where your crops in Stardew reliably reward you for hard work and planning in ways most jobs do not. However, sometimes we optimize with whimsy: I grow corn purely for aesthetic reasons, despite it making me less money.

One of my farm’s sheds for jam and wine production.

The best-optimized Stardew farms are about pleasure in efficiency itself, rather than serving markets. Stardew players experience no serious money pressures, and those showing off perfectly-organized productive units receive little meaningful reward, because these farms produce more money than needed. Video games let us simply opt out of what Karl Marx and Søren Mau call the “mute compulsion” of economic power—the way market imperatives like rent coerce us to work without any one political authority directly forcing us to—in a way we cannot in reality. But the fact that we want to is telling.

A world beyond market exchange is a revolutionary, not reactionary, vision. Gerrard Winstanley and his Diggers condemned “buying and selling” in general—as “the great cheat, that robs and steals the Earth from one another.” This critique of market exchange itself is an early example of the most incisive critiques of capitalism. Marx’s Capital begins with analysis of the commodity form. Real things—land, food, a linen coat—all have use-values, i.e. worth deriving from their specific properties, like keeping us warm or fed. But these commodities also have exchange-values. Production merely for market transaction reduces real things to “a bare gelatinous blob of undifferentiated human labor,” values of “crystallized” human time and effort. These are interchangeable because universal market exchange demands they be. The rest of capitalism follows: production is organized to produce exchange-value for the market, and political power enforces this through private property.

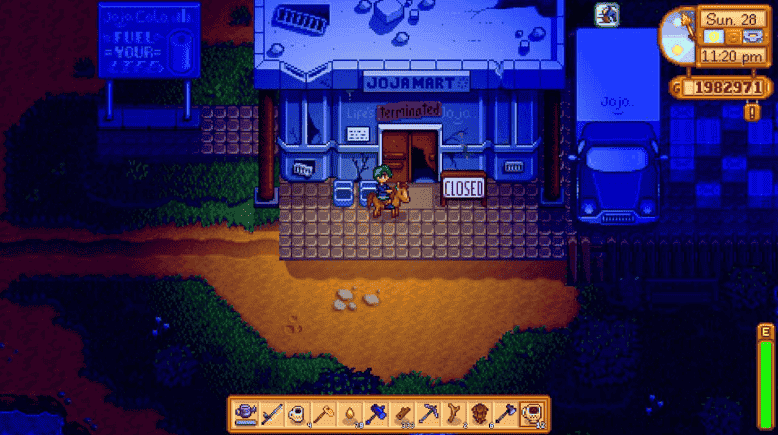

Gerrard Winstanley’s ideal commons, like Marx’s vision of communism, was a world governed by real needs and wants rather than market value. A yearning for production beyond market-driven commodities is also central to Stardew’s plot and appeal: the game’s community center storyline explicitly pits use-values against exchange-values. The bundle deliveries the community center restoration requires consist of specific goods: you don’t need 1000g worth of goods, you need three bushels of corn, a rare fish you can only catch when it’s raining in the evening in summer, and a bottle of wine. These deliveries unlock infrastructural improvements to the town: a minecart-based rapid transit system, the return of the regional bus. If delivering bespoke bundles of goods feels like too much work, you can replace the community center with a Joja warehouse, which allows you to just buy these upgrades—abandoning the Mayor’s vision of a restored community center for Joja’s local development promises.

But few players do this, and the path’s significance is primarily as a choice for us to deliberately reject. Doing so eventually drives Joja out of town. That rejection is meaningful. Americans who romanticize the farm as a space of wholesome community and a better relationship with the earth are wrong. But our desire for these things is a hope reflected in commons systems across human history. Stardew Valley is not a commons simulator, but the Stardew farm’s “cozy” critique of modernity resonates with players because and where it emulates the commons, a world beyond “buying and selling.”

Joja Mart at night, closed forever.

It is still a small farm whose attractiveness comes down to America’s deeply-embedded Jeffersonian vision of yeoman farmer independence—a vision that is genocidal and patriarchal. Viewers of “homesteading” and “tradwife” social media content don’t have a monopoly on misguided pastoral romanticism either. Sociologist Elinor Ostrom’s work on the viability of the commons—contrary to eugenicist Garrett Hardin’s false “Tragedy of the Commons” fable—was pathbreaking, but it was also a defense against the state as much as the market, with links to right-wing economist James M. Buchanan rather than Marx or Winstanley. Anthropologist James C. Scott developed a critique of “high modernism” and state power that was quite compatible with neoliberalism. Both echoed arch-neoliberal Austrian School economist Friedrich Hayek.[1] Hayek believed in the tacit knowledge of local individuals over the intentional designs of institutions—a philosophy that might seem emancipatory, but came from a theory of the mind and society that rejected any conscious “planning” altogether. Agrarian romantic cultural output and theoretical frameworks both have limited horizons.

In the words of geographer Lee-Ann Sutherland, “players of Stardew arguably consume rurality as a life raft—a temporary escape from urban life.” Most players are mirroring their character’s retreat from the life of a wage-earning worker to a rural capitalist. Likewise Scott proposes a retreat into rurality—the local knowledge of individual communities, the subtle “infrapolitics” of small villages. When the state must act, Scott advises it to “take small steps” and “emphasize reversibility.”

Cultivating Community

In real life, building a community center will not drive Amazon out of your town, driving Amazon out of your town will not resolve its corrosive effects on American life, and taking small and reversible actions only guarantees your impacts will be small and reversed. Gerrard Winstanley and his defeated Diggers would be among the first in line to warn us that you cannot do or sustain land reform purely from below. Anyone can oppose “high modernity” for any number of reasons—believing in a possible future commons asks far more of us, now and going forward. Our collective affinity for the agrarian past contains possibilities for a liberated future only if we consider what we are for, not just what we are against.

As a retirement hobby, my father built a greenhouse. After a long career in education, he dreamed of retiring, bafflingly in my mind, to manual labor. This wasn’t a romanticization of physical work—he had seen the toll that took on his father, a textbook industrial proletarian who worked in a shoe factory in Somersworth, NH. Rather, my father had always taken pride in scrupulous care and rich appreciation for the world around him. He determined and valorized the finest gas station soft drinks, carefully cultivated the plants around the driveway, proudly and enthusiastically gushed about opera and comedy alike. This ethos of meticulous affinity shaped my childhood video gaming experiences too: my father purchased my brother’s Xbox 360 with a shoebox full of ones. The box held every one-dollar bill he had received in change for ages, insisting they would in time accumulate to something meaningful. Cultivating flora was just the same impulse applied to soil and carrots.

I joked that he and my mother were doing “Stardew in real life” with their greenhouse, because they were. He didn’t get to spend much time there—he died of cancer shortly before his planned retirement. My mother takes care of it now, and the result is a steady supply of fruits and vegetables to family, friends, and food banks. Stardew players, likewise, find joy in growing gifts for other characters, or working the farm with friends in the game’s popular multiplayer mode. This kind of small production does not in my view represent an economic model for better future agriculture. As Gerrard Winstanley knew, we must go forward, not back. My parents’ little greenhouse doesn’t scale—but many of the impulses behind their real Stardew and everyone else’s video game do. In a meditative trance once, Winstanley heard the following message: “Work together; eat bread together.” If we yearn for this in our games, it’s because the commons, and not just The Farm, haunts us.

Note

[1] The infamous “tragedy of the commons” fable holds that public goods are invariably corrupted by personal use, as individuals who gain all the benefit of overusing resources but only a small amount of the harm choose to prioritize their needs over the community’s, leading to the eventual destruction of common resources. It was popularized in a 1968 paper by eugenicist Garret Hardin. Elinor Ostrom is best known for her work on the commons, in which—following real examples of land management today, rather than the “tragedy of the commons” hypothetical—she found that human communities are perfectly capable of organizing long-term use rights collectively. James McGill Buchanan was one of the creators of “public choice theory,” a framework that applied methodological individualism and “rational choice” to politics; this was linked to his important organizing work on the American right. Friedrich Hayek’s most famous work, the influential 1944 The Road to Serfdom (though the 1946 Reader’s Digest version was arguably more important), argued that virtually any government “planning” led to tyranny. His ideal state was a kind of referee that maintained market rules, particularly by protecting markets from democratic will. James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State criticizes what he calls the “high modernism” of the 20th century, a top-down technocratic governance approach. In his account, by attempting to make subjects visible to state authority, the high modernist state erases the local and the individual, with invariably catastrophic consequences.

References

Coronil, Fernando. “Smelling Like a Market.” The American Historical Review 106, no. 1 (2001): 119–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/2652229.

Hill, Christopher. The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution. Temple Smith, 1972.

Hayek, Friedrich. The Road to Serfdom. Institute for Economic Affairs, 2005.

Mau, Søren. Mute Compulsion: A Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital. Verso Books, 2023.

Mitchell, Timothy. “Everyday Metaphors of Power.” Theory and Society 19, no. 5 (1990): 545–77.

Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press, 2020.

Sutherland, Lee-Ann. “Virtualizing the ‘Good Life’: Reworking Narratives of Agrarianism and the Rural Idyll in a Computer Game.” Agriculture and Human Values 37, no. 4 (December 1, 2020): 1155–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10121-w.

Winstanley, Gerrard. “The True Levellers Standard Advanced,” 1649, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/winstanley/1649/levellers-standard.htm.

“A Declaration from the Poor oppressed People of England,” 1649, https://www.diggers.org/diggers/declaration%20from%20the%20poor%20oppressed.htm.