Data Threshers

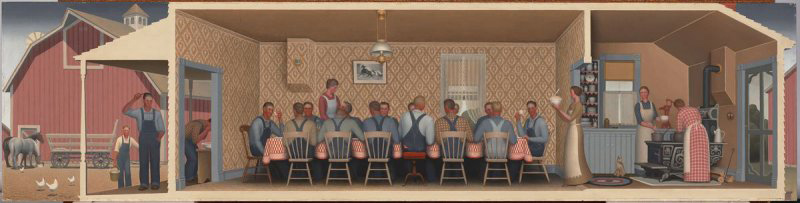

“Data Threshers” is a simulation portrait that experiments with the representation of metabolic conflicts in multiple scales of time, space, and perspective. Formally, the video takes its cue from Grant Wood’s 1934 painting Dinner for Threshers. The piece seeks to stage an encounter for the viewer with the strange new rhythms of data mining, logging, and farming that are emerging along historical patterns of development in America’s heartland.

Dinner for Threshers, Grant Wood, 1934, Oil on Hardboard, 20 x 80 in. (50.8 x 203.2 cm), Art © Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Exploding the idyllic myth of rural American life today, “Data Threshers” brings together the grain silo and the data center—two architectures of supply, storage and circulation—and documents the transforming relationship between technology, land, and labor. The piece seeks to stage an encounter for the viewer with the strange new rhythms of data mining, logging, and farming that are emerging along historical patterns of development in America’s heartland. The act of threshing, the forceful separation of the edible grain from the inedible chaff, moved from the stone floor, to the wooden table, to industrialised fields. Today, data farms require labour beyond machines to manipulate and maximise their products: the act of being online obliges us to participate in the parsing, separation, and reassembly of digital patterns (and their yields) beyond our grasp.

The data centers emerging in the American hinterlands are an important moment in the re-articulation of the military-agricultural-industrial complex from farming animals to farming human behaviour. Simply getting into a data center today involves: navigation with google maps, a now household military technology designed for remote sensing and accurate air strikes (Kurgan, 2013); driving through fields of crops treated with fertiliser, an innovative repurposing of WWI chemical weapons (Hager 2009); gaining clearance through multiple rows of barbed wire fencing, a design perfected on the flesh of cattle that is now used to keep humans in detention (Netz 2010); only to see rows of Caterpillar diesel engines in a backup generator, an instrument that moved seamlessly between the tractor and the tank (ibid). Within the rural data center we begin to see the prevailing tech apparatus—Big Tech, ‘Platform Capitalists’, the Silicon Six, etc—seeking to remake the planet as a kind of digital plantation, where the basic underlying components of profiteering can be replicated or unearthed endlessly, at scale, and without friction.

At the risk of online/offline binaries or of falling prey to a reductive notion of “opting out” of digitised life and the associated privileges of exclusion, “Data Threshers” promotes a position that is out-of-line with digital narratives produced for us by a globalising tech empire. Being part of a line but not benefitting from the connection is a feature of imperialism that extends to all those disenfranchised from dominant networks of power. And as ongoing histories of struggle, persistence and defiance reveal: as long as there have been lines directing and controlling flows there have been ways to alter or subvert them.

Getting On-the-line

One of four Facebook data centers in Altoona, Iowa. At 2.5 million square feet, the buildings begin to merge with the horizon. Photo courtesy of the author.

With over 3 billion people online today, the total energy footprint of the information and communication technology ecosystem is on par with that of air travel.[i] A recent article by The Guardian Environment Network estimates that by 2025, the production, circulation and storage of data is scheduled to use a fifth of the world’s energy, a small fraction of which most would consider ‘clean’. Greenpeace, the leading NGO confronting platform capitalists and their energy practices, reported that a single Google search can burn anywhere from 0.4 – 7.0 grams of carbon, or the equivalent of driving a car 52 feet. According to researchers at Lancaster University, the constant online traffic associated with new trends in binge watching, streaming and internet multi-tasking account for the greatest environmental challenges ahead.

In early 20th century Britain, getting ‘on-the-line’ became a popular term to describe settlements connected to the material goods guaranteed by a railroad. Connection was quite literally referred to as the manifestation of lines—a line being the shortest distance between two points—materialised first on paper, in the telegraph wires, the railroad tracks of an expanded territory and later the light speed travel of fiber optic cables. Settler industrialists, corporations, individuals and groups who had access to these powerful networks came to be associated with the economic benefits of a progressive, technological society. Today, the term ‘online’ is reserved for individuals who are ‘active’ or ready-at-hand to participate in digital communication, omitting what was historically considered a social continuum of material flows.[ii]

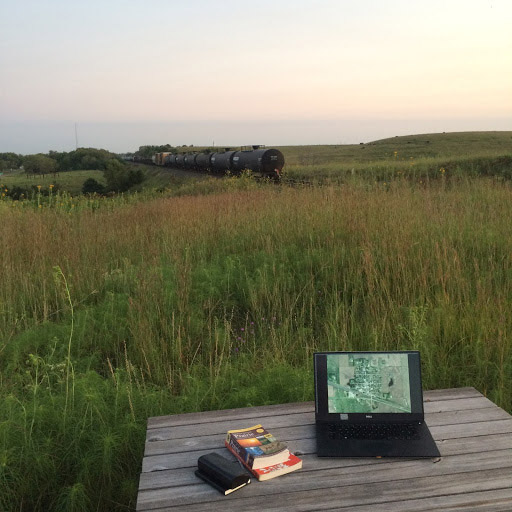

The Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) railroad pushes commodities through the tallgrass prairie in Matfield Green, Kansas. The 25ft ‘right of way’ zone offset from either side of the track is considered private property owned by BNSF, used to circulate private and public utilities like electric power, telegraph, cable television, water, gas, oil, petrol products, steam, chemicals, sewage, drainage, irrigation, and, most recently, fiber optic cables for internet infrastructure. Photograph courtesy of the author.

The ascension of online infrastructure could not be clearer than in the American Midwest. In order to feed the growing capitalist centers of Chicago, Minneapolis and St. Louis, on-line settlements were established by railroad speculators in the 19th century to expand the railnet and penetrate new markets, at irreparable cost to non-commercial forms of life and indigenous world making projects. The patterning of these developments have come to be known as ‘tracks and elevators urbanism’ as railroad companies frequently commissioned grain elevators as the first buildings from which the towns organised themselves. An architecture of supply populated these stolen hinterlands, as plantation logics and the associated ruins of disease, oppression, and built obsolescence moved northward.

The capillary networks that moved early twentieth century commodities established the routes of data circulation, transfer and power supply seen today. Municipal and corporate actors splay reams of fiber cables, centralised and edge data centers, colocation hubs, transfer stations, ‘fiberhoods’, 5G small cells, cell towers, power stations, wind farms and solar panel fields, big box stores, underground and open pit mines, wifi routers and charging points across the extractive networks of yesterday.[iii] An observer would be forgiven for not knowing the difference between a data center and a Walmart, an industrial feedlot and a Bass Pro Shop. The large, anonymous buildings that inhabit the Midwestern plains, keeping a large part of the country online, expand and expand even as they recede from popular consciousness.

Mining, Logging, Farming, Harvesting Data

We are told that the server ‘farms’ housed inside data centers are there for data logging, data mining, data farming and data harvesting, evoking the lost frontier of industrial capitalism in an otherwise postmodern and financialised economy. What better way to naturalise one’s services than to borrow the language from the hegemonic story of human civilisations? In architectural theory, archaisms such as the ‘cave’ or the ‘farm’ “exploit a disjunction between what [a] thing represents and what it does,” asserting a primeval or pre-capitalist expression that tends to mask new deployments of capital (Scott 2016). The processes of mining, logging, farming and harvesting data contain both spatial and political correlates: exceeding their physical constraints, extracting as much from their subjects as the geophysical processes and products they rely upon.

Mining

Fiber optic ‘prairie grass’ greets visitors at the LightEdge Solutions data center, located within an expanding underground business park outside of Kansas City. The 4.5 km2 artificial cave was built in the bluffs above the Missouri River. Photograph courtesy of the author.

In fact, data centers are increasingly found inside of the depleted mines, abandoned grain elevators and overused agricultural lands of the American hinterlands. In 2014, LightEdge Solutions moved their data operations to an abandoned limestone mine turned business park outside of Kansas City, Missouri due to advantages in security, cost and energy efficiency, particularly with cooling. The center connects to new generators that have replaced the footprints of former extraction buildings, while their clients mine valuable nuggets of information buried within heaps of data. With names like ‘Info Bunker’, ‘Cavern Technologies’, and ‘Iron Mountain’, these underground data centers evoke the paradox of being hyper secure yet hyperconnected.

Logging

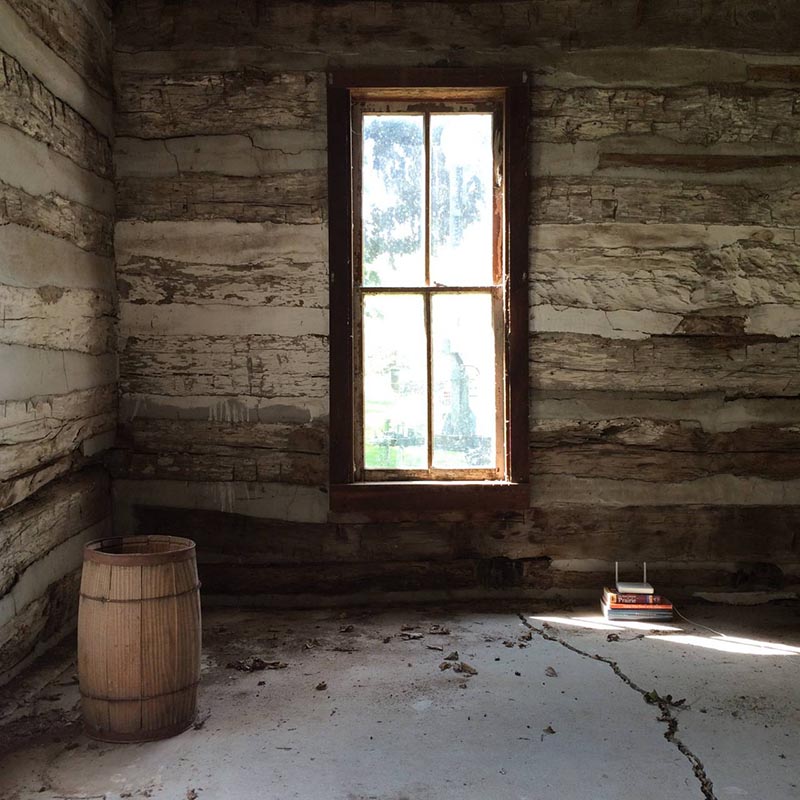

A wi-fi router keeps visitors online in the Pioneer Bluffs log house in the Flint Hills of Kansas, constructed in 1908. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Early american logging operations usually floated felled timbers down-river to be sawed at mills; buildings which are now finding new life as data centers. Their proximity to water allows for efficient cooling. No longer entangled in the construction of log cabins or paper milling, these spaces have been freed for the logging of data.

In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff argues that big-tech makes as of yet unacknowledged claims to human behaviour and experience as ‘the last virgin forest’ of extractive capitalism (Zuboff 2020). As digital consumers log-in to social media platforms and search engines, a logbook of their actions create profiles useful for those who would automate and preserve their behaviours for profit. Recently, the philosopher Byung Chul Han warned that big tech companies using big logbooks have the ability to ‘steer the future psychopolitically’ (Han & Butler 2017). With the average North American household consuming 190 GB of data a month from ten or more devices, there’s plenty of material for navigation and intentional disorientation.

Farming

Yahoo’s chicken coop-inspired data center relies on the circulation of heat to increase air flow. Photo accessed online at https://buffalonews.com/2014/07/10/yahoo-repurchases-18-acres-of-lockport-industrial-park-land/

In 2009, The web services provider Yahoo created the ‘Computing Coop’, a server hall that takes the logic of battery cages for hens to farm a resource of a different kind. Because of the pitched roof, the warmer the coop gets, the more draft is created. Technologists worked with farmers to perfect the profile of the coop, finding parallels between the heat of server racks and racks of productive hens. Farmers manipulate the land to maximize their yield using irrigation, pest control, crop rotation, and fertilizers influenced by calendars, rule of thumb, and past iteration. Data farmers use large-scale designed experimentation to grow data from their models in a manner that easily lets them extract useful information. They work within discourses of insecurity, risk and the logic of preemption.

Harvesting

A 500GB Seagate hard drive from the early 00s sits in the foreground of steel grain silos from the 70s and 80s in Nashiville, Illinois. ‘Form follows supply’ in the architectures of storage, reflecting the health of markets and developments in technical efficiency. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Farmers collect and store crops in anticipation of future climatic hardships. Harvesting is often accompanied by a celebration of and the administration of a surplus of crops. Harvesting data involves collection and storage, with the expectation of future reward. In data terms, machine learning algorithms convert (unknowingly) siphoned-off behavioral data surpluses to target ads to consumers.

To produce space on the basis of storage – as seen in the rational grids of on-line settlements and their grain elevators – is to ignore the crisis onset by overabundance. The communities and identities formed by logistical settlements are weakened by the creation of a surplus bought and sold not on their terms.[iv] The question is not how to regain ownership of data while online – a question most technology firms find to be existential and therefore not possible politically – but how do users of online platforms produce a surplus of data they can control?

Digital Permaculture

A wireless internet cell tower behind the Bazaar Cemetery in the Flint Hills region of Chase County, Kansas. Thanks to the rocky soil conditions, no field crops were able to be plowed. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Can the Midwest’s increasingly technology based economy change the trajectory of an expanding and energetically unsustainable information and communication ecosystem built along racialised and ruralised divides? Instead of providing users with more energy efficient devices in exchange for the increased size and energy use of data centers, can we imagine low tech, asynchronous communication networks to serve the digitally divided plains? Building upon the successes of internet cooperatives and community owned mesh networks, might there be a set of guiding ecological patterns, unique to the prairie, suitable for deindustrial data usage: a digital permaculture for the exhausted soils and spaces of American hinterlands?

Notes

[i] For an energy forecast of digital infrastructure, see: Jones, Nicola. “How to Stop Data Centres from Gobbling up the World’s Electricity.” Nature 561, no. 7722 (2018): 163–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06610-y.

[ii] In the Midwest, rivers often preceded the lines, as French aristocratic families traded fur along river routes, displacing indigenous americans or forcing their gradual reliance on mercantilism. River networks provided less friction than the land and were powerful orienting features for traders.

[iii] For more reporting and analysis on the physical infrastructure of the Internet in the Midwest see: Burrington, Ingrid. 2015. Why Are There So Many Data Centers in Iowa?. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/12/why-are-so-many-data-centers-built-in-iowa/418005/, and Burrington, Ingrid. 2015. How Railroad History Shaped Internet History. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/11/how-railroad-history-shaped-internet-history/417414/

[iv] Midwestern farmers will remember the agricultural systems crisis in the 1980s which saw the overproduction of grain strongly contributing to a commodities market crash. Large numbers of land foreclosures and, tragically, suicides among farmers, were recorded as neoliberal federal policies expanded global markets, establishing pathways for agribusiness monopolies to consolidate small farms.

Bibliography

Hager, Thomas. 2009. The Alchemy Of Air. New York: Broadway Books.

Han, Byung-Chul, and Erik Butler. 2017. Psychopolitics. New York: Verso.

Jones, Nicola. “How to Stop Data Centres from Gobbling up the World’s Electricity.” Nature 561, no. 7722 (2018): 163–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06610-y.

Kurgan, Laura. 2013. Close Up At A Distance. New York: Zone Books.

Netz, Reviel. 2010. Barbed Wire. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Scott, Felicity. 2016. “Re-Attachment”. In Archaisms And Architecture. https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/82182/archaisms-and-architecture/.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs, 2020.