Editor’s note: In Ghana on the Go, Jennifer Hart tells the history of how being a driver in Ghana became a contested vocation. Today on Platypus, she talks with Ilana Gershon about her work on infrastructure and profession. They talk through how driving emerged as a profession in the context of British colonial efforts to strategically introduce transportation technology, and about how this history has shaped the current precarious and often stigmatized nature of the job. Ultimately, Hart argues that the history of Ghanaian roads and motor cars is also a history of how integral human labor and labor conditions are to the development of infrastructures generally.

Ilana Gershon: What is striking and possibly unexpected about your book is that to tell the history of Ghanaian drivers is also to tell the history of infrastructure. Indeed, you make a very compelling case for how studies of infrastructure need to become far more conscious of labor history once we accept that humans are integral parts of evolving infrastructure. If you were going to explain the arc of your book as a history of human infrastructure, what are one or two of the changes in Ghanaian drivers’ lives over the course of the twentieth century that you would want readers to know about?

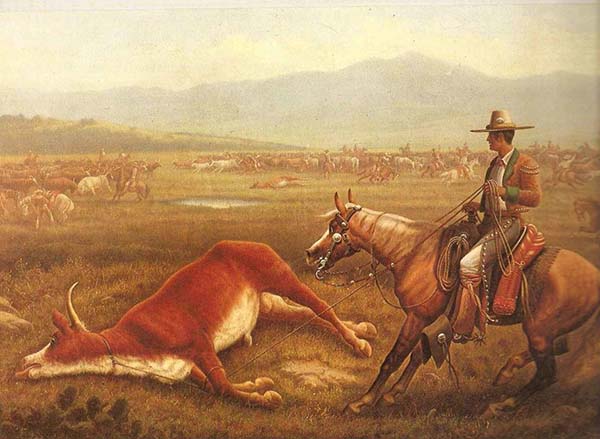

Jennifer Hart: We often write and talk about the culture of automobility as globally homogenous – an implicit byproduct of the technology of the motor vehicle. It becomes a sort of narrative trope. Paul Edwards called roads the “invisible, unremarked basis of modernity.” But the history of Ghanaian drivers highlights that this technological and infrastructural story was profoundly shaped by the people who use that technology and infrastructure. In the Gold Coast, early vehicles were imported by European administrators and import companies and used as symbols of political domination and control. Cocoa farmers, who used their profits to invest in motor vehicles and employed them to transport cocoa between rural farms and coastal ports in the 1930s and 1940s, created the foundation for a new culture of motor transportation in the colonial Gold Coast. African entrepreneurs, who purchased and operated motor vehicles, controlled this new form of automobility, using the technology to transport goods and people throughout the colony. That autonomy and control over technology positioned drivers as respectable members of modern society, providing a public service for private profit. The growth of cocoa farming enabled Africans to purchase and deploy motor transportation to expand the economic, social, and cultural possibilities for a wide array of Ghanaians in the colonial and early postcolonial period. (read more...)