This blog post is about the popular augmented reality game, Pokémon GO. If you are unfamiliar and/or want a brief overview of it and its cultural history, this is a useful resource.

As a virtual world anthropologist and a Pokémon nerd, I have become immersed in Pokémon GO. As the game continues to gain traction and I wander around meeting strangers and friends who are also playing the game, I have taken note of numerous issues of anthropological concern, like new forms of social interaction and the re-mapping and flattening of cityscapes. Colleagues and I have even speculated about whether Pokémon GO is a virtual world—by which I mean a computer-simulated, persistent, and shared environment online—and, if it is such a world, how it represents one that is visible even to non-players.

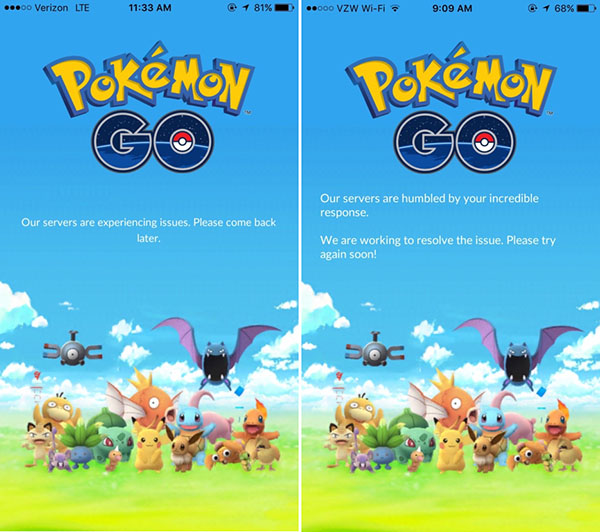

Participating in and observing the Pokémon GO phenomenon, I’ve found that players have been confronted by another recurring topic related to visibility: the visibility of game servers. I recently attended a large gathering of about 1000 Pokémon GO players in downtown Riverside, CA. We all walked around together, yet apart, huddled among small groups of friends with phones in hand, capturing virtual pets. Servers are the typically invisible and distant machines that allow such an event to happen. They connect people to the game world and to one another by receiving and returning signals to and from our mobile devices. They are an integral part of the ecology of media that enables the shared experience of being in a virtual space overlaid upon the actual world—and, curiously, players have a vague understanding of this. Pokémon GO servers have become very visible. If you ask any Pokémon GO player, servers are to blame for some of the greatest downfalls of the game, like faulty connections, glitches, outages, and lag. Developers have repeatedly mentioned servers as the root of many issues with the game, and, as a result, many players continue to point fingers at servers. So why have servers, things we can’t see or even explain, become the targets of so much anger and frustration? How can we characterize the very visible role servers play in the social worlds of Pokémon GO? (read more...)