Experience, disability and design.

What is an experience and how can it be conveyed and communicated to others? “A focus on “The Experience” signals a technology has been designed with a consideration for the user’s experiences. It is supposed to indicate a technology’s role and contribution to everyday life, and the likelihood of its success once implemented.

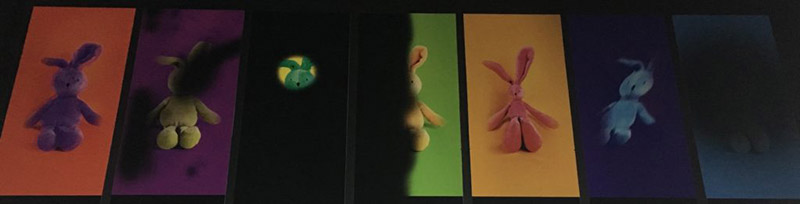

One of the images on display at the Invisible Exhibition portraying different kinds of visual impairment: diplopia; glaucoma; pigmentary retinopathy; hemianopia; myopia; astigmatism; macular degeneration (left to right). All photographs courtesy of the author.

Given its popularity in design contexts, the term “experience” seems unusually rare in anthropology, with a few notable exceptions (e.g., Bruner, 1986; Turner, 1986; Hastrup, 1995, for example). This is so despite the fact that we, as anthropologists, can definitely be said to “experience” a way of living other than the one we are used to when we carry out fieldwork. This experience begins with our first encounter with another culture and its people, and continues into the writing stage, with our concerted attempts to communicate the complicated cultural aspects of the places and peoples we study with. Writing about and communicating other ways of living in text, with a focus on eliciting a sense of how their everyday lives are “experienced,” is central to the anthropological task of making the world safe for difference – whether or not we share these ways of living or are outsiders.

This focus on experience often extends to the museum exhibition. Both The Invisible Exhibition and Dialogue in the Dark (DitD) are exhibitions which center on (the creation of?) an experience – of being blind – and suggest that this experience gives visitors the chance to encounter another world and view the world they take for granted from a new perspective. This is what DitD promises on their webpages. This desire to stage an encounter (a first encounter for most), remind me of the anthropologist’s first day “in the field,” and the frequent use of an impactful vignette, which generally begins the conventional anthropological monograph or ethnographic tale. In fact, I had my own first encounter when I visited the Invisible Exhibition in the middle of July, 2017 and have my own vignette to share: My experience of the Invisible Exhibition and how what it was like to play at being blind for an hour.

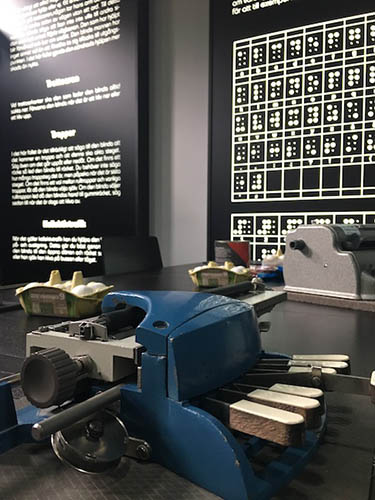

Sitting and waiting in the exhibition center’s cafe, I amused myself by playing games on my mobile phone, glancing around and anticipating the start of the guided tour. There were other guests in the cafe, also waiting, I assumed, and others who had already begun their tour and were seated in front of a braille typewriter with their guide (see the picture, below). This group were trying to type their name in braille, and were talking and laughing loudly as they tried. Their names correctly typed in, the group got up and moved towards the entrance to the exhibition and the pitch-black rooms that awaited. It was only once the family had gone into the darkness that it was quiet enough in the exhibition center for me to notice the music playing on the loudspeakers and the “tock-tock” sound coming from the device designed to lead the visually impaired employees and visitors to the entrance door. The sound was loud, constant, and exhaustingly regular; the music sickly sweet and easy to ignore. Soon after, the exhibition manager, Lilla, came up to us and told us that now it was my group’s turn. There were four of us; our guide, Sandra, was waiting by the braille typewriters. Our experience of what it was like to be blind had begun…

One of the braille typewriters at The Invisible Exhibition, Stockholm, 2017.

Or had it? What I experienced was something that was somewhat more personal and egocentric than the previous visitors’ experiences, at least as quoted in the Invisible Exhibition’s brochure and website. What I took away from the exhibition was not about what it is like to be blind or visually impaired. The exhibition led me to the surprising realization that I am actually quite competitive when it comes to meeting challenges. During the entire guided tour, I competed (with myself) to see if I could cope with not being able to see. I had my eyes closed for most of the time, so that I could focus better on my other senses: touch, hearing, my sense of smell. In one room, which portrayed an art gallery, we were asked to touch a number of different sculptures and try and identify them without being able to see them. It was here my competitive streak burst into overdrive, and I got the confirmation I was seeking – that I could, simply with touch and my memory of images that I had seen, identify Nefertiti, the Laughing Buddha, Michelangelo’s “David,” a Dalecarlian horse, Atlas carrying the world on his shoulders and so on. Even so, I did not feel that I was experiencing what it was like to be blind. I could easily recognize the shapes of classical sculptures and knew their names because I had seen images of them before. It was difficult for me to experience what it would have been like if I had been blind and never seen these sculptures. I asked Sandra, “I understand how I am able to identify these sculptures fairly easily because I have seen countless images of them and have memories which I can use to compare with what I touch; but how can you know what these sculptures depict if you have never seen them?” Sandra answered quickly and with a sharp, “How do you know I have never seen them?”

What a great answer. How did I know that? Had I even asked Sandra anything about her visual impairment? Or had I simply assumed that she was blind and had never been able to see? Yes. I had made a stupid assumption and, as Sandra explained for me later during our interview, there are other ways of “seeing.” Sandra had had poor vision since she was young because of glaucoma. She had perhaps not seen these sculptures, but she had read about them and could use the descriptions and the mental images of the objects that the descriptions called forth to compare with what she identified through touch. Feeling the form and material of a sculpture together with a written description is enough to “see” and identify them, Sandra explained. She added that this, too, is something that depends on a person’s character and habits. Some people with visual impairment rely more on their sense of smell or hearing rather than touch. It varies, and this variation in the ways in which people with visual impairments navigate the world, extends to my experiences at the Invisible Exhibition – it was an experience all my own. One that was determined by my personality, and by how I have learnt to meet challenges during the course of my life.

What this blog post suggests is the impossibility of a universal “experience” that can act as evidence, information, and testimony for design decisions when designing technology with disability in mind. It is a problematisation of what the notion of “experience” can and cannot convey, what it is, and what kinds of assumptions underlie the use of the word in connection with technology design and disability. What do we win, lose and what is overlooked? Not only do I take issue with the notion of “experience” in design contexts but I also question the part it plays in museum exhibitions centered on giving the visitor an experience of what it is like to be blind or to have a visual impairment. What happens to the importance and value of “experience” when, rather than increasing understanding for what it means to be visually impaired, visitors learn more about themselves; or worse, when they lose empathy once they understand what it is like to not be able to see? It was tricky, with an exhibition like the Invisible Exhibition, to establish a balance between eliciting empathy and understanding from the visitor, and running the risk that they lose all empathy simply because the experience was not taxing enough.

“Let your sense lead you on an interactive journey…” The Invisible Exhibition, Stockholm, 2017.

While DitD promises to offer “immersive experiences,” the Invisible Exhibition’s goal is, according to exhibition manager Lilla Felfoldi, to show the visitor that the blind and those with visual impairments are people, just like anyone else – they just do things differently. One purpose of the exhibition is to portray the everyday life of the blind or those with visual impairments, and to give the visitor the opportunity to ask and have their questions answered by their guide. DitD shares this goal, but adds that their “…experience helps us to overcome false sympathy, prejudices and stereotypes. In ‘Darkness’ interest replaces ignorance, and lack of understanding changes into empathy.” It is not difficult to imagine a certain type of person arguing that, “if I can cope with not being able to see for an hour without any kind of preparation or education, then anyone can do it.” This is however not the greatest challenge with the exhibition, according to Sandra. What is more difficult is combating the tendency visitors have of forgetting that everyone is an individual and not everyone is the same, even among the blind and those who have visual impairments. Each person has their own personality which influences they way they live their daily lives and not all blind of people with visual impairments can be put in the same category, said Sandra.

I am far from the first to point out how experience in all aspects is a “product” of our personalities, the pre-conditions of our lives, and how we engage with the world (Dewey 1934 for example). An important extension of this, and one which is only now being acknowledged in design circles, is that experience is perhaps not the stable entity it was presumed. It was not so long ago that technology design that considered the “end user,” design processes that involved testing and asking the general public about a technological prototype e.g. participatory design, were collected under the banner of user experience in many industry settings. User experience or UX design signaled that the designer of a technological artifact saw merit in the views of those they hoped would buy their product. As a designer, it was important to understand these potential consumers and the situations in which their technologies would be used. This underlying design philosophy has critical “implications for design” in all instances. When designing technology for people with disabilities, it is even more critical to recognize the personal, individual, and multiplicity of (in this case) visual impairment. Reaching this goal might prove just as hard as it is to avoid homogenization of cultures and people in anthropological texts, but as some ethnographies and debates in anthropology illustrate, it is not an impossible task.

References

Dewey, J. 1934 [2005] Art as Experience, Penguin Books, New York, USA

Hastrup, K. 1995 A Passage to Anthropology: Between Experience and Theory. Routeledge, London, UK.

Bruner, E.M. 1986 Introduction in Turner, V.W. & Bruner, E.M. (eds) The Anthropology of Experience, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, USA

Turner, V.W. 1986 An Essay in the Anthropology of Experience in V.W. & Bruner, E.M. (eds) The Anthropology of Experience, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, USA

1 Trackback