Overlapping experiences of confinement

Like many others in Colombia, Nairys[1] is a campesina for whom the experience of confinement has been one of dramatic disruption. Marked by restricted mobility, which means very difficult access to water and subsistence crops, being locked down also implies the reduced possibility to buy medicine, food, and other basic supplies. As for many other women, stay-at-home ordinances have also meant more care work, as the responsibilities of feeding and tending for her relatives fall heavily on her. Likewise, confinement involves being permanently under the same roof with her partner, which has exposed Nayris to more possibilities of being mistreated and abused by him, particularly as pressures over mere subsistence increase.

Although one might think that Nairys’ struggles are a consequence of the nation-wide measures taken by the Colombian government since March 25, 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, this is not the case. Paramilitary groups operating as de facto authorities in rural areas such as Chimborazo, in the Colombian Caribbean, where Nairys and her community faced confinement between 1999 and 2000, imposed a violent order where all kinds of restrictions worked as effective mechanisms for land dispossession. Her story is just one of many similar stories that abound in rural Colombia and that, despite the signing of a peace agreement between the government and the now-dissolved FARC guerrilla in November 2016, persist.

The Colombian countryside has a long history of forced confinement by military means, sexual violence, blockages, as well as difficulties in making a living and accessing food, medicines, and healthcare in the midst of violence and authoritarian rule. The circumstances created by current policies in the context of the ongoing health crisis are too familiar to many people who have historically experienced the war in Colombia. This is true as well for countries like Palestine, Vietnam, and elsewhere. It is also the stark reality historically imposed on millions of people around the world by prisons, detention camps, walls, and policing, among other means made legal.

Based on the current situation in Colombia, in this text we seek to analyze the continuity and fluidity of practices and discourses of militarization in the context of war, post-conflict, and the current pandemic. Militarization appears as a government technology that is easily recycled and redeployed by the state (as well as by illegal armed groups) in places where war has become an ordinary aspect of daily life. We argue that it is precisely in contexts that coexist with a war-torn past and present that the use and reuse of militarization—this time in the name of collective health—becomes even more dangerous and hostile.

The (para)militarization of life

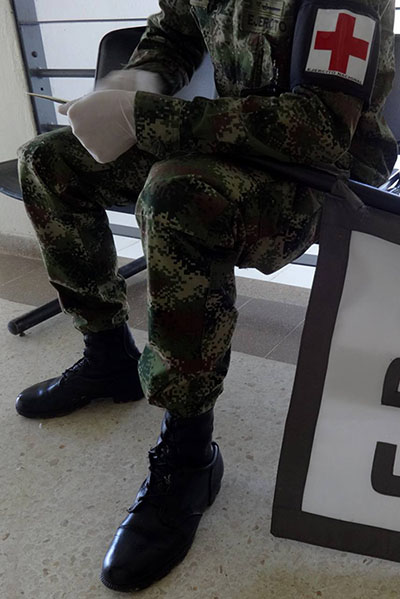

Member of the Colombian army with a band on his arm indicating his specialized training in health care. Photo by Lina Pinto García.

Discourses and practices of warfare have rapidly become available in the wake of the current health emergency. In places like Colombia, it is disturbing to see how readily the state has adopted the militarization of public health; more disturbing are the ways in which many citizens easily accept and often demand this form of control in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Like Cynthia Enloe, Catherine Lutz and Neta C. Crawford, and others, we see the dangers of using “war” as a metaphor to make sense of the actions and mindset needed in the current situation. We too are aware of how war metaphors are clearly bound up with the very concrete reality of those whose bodies, daily itineraries, and lived spaces are controlled through the use of state (or state-sanctioned) violence. This is even more the case in the face of emergency and “natural” disasters, as the images of Naled fumigations in Puerto Rico after the Zika epidemic or the deployment of military troops as first-line response after Katrina in New Orleans remind us.

As we write, police helicopters flying over Bogotá, the capital city, fill our nights with an unsettling noise. In Cota, a town near Bogotá, soldiers speaking from army helicopters proudly let people know that “The national army takes care of us all. Homeland, honor, and freedom. Stay at home.” Beyond this not-so-gentle reminder of a powerful regime of militarized surveillance and repression at work, for many people in Colombia, physical isolation equals lockdown in the form of heightened criminalization, official permits to go out for groceries organized according to ID numbers, 24/7 curfews for children and the elderly, and road blockades. An all too familiar “if you see something, say something” type of suspicion between neighbors seems to have quickly installed. The mobilization of fear of contagion has generated a constant and unhealthy climate of surveillance in different towns and cities, while reports of the assassinations of social leaders and former guerrilla combatants fill media outlets.

Last Wednesday we woke up to the news that nine municipalities in Cundinamarca (the central state to which Bogotá belongs) were militarized to prevent the spread of the coronavirus pandemic. Arguing that the failure of some to comply with quarantine regulations was due to a lack of awareness, the governor of Cundinamarca, Nicolás García, presented the measure as a way to make the population understand “that this is not a game.” Anticipating some criticism, he spared no effort in using euphemisms. “It’s not militarization, it’s acompañamiento (accompaniment) by the army,” he told the media. Similarly, state authorities in other cities and municipalities have also militarized the streets. This is the case in Barrancabermeja, Ibagué, Jamundí, Pasto, Popayán, Riohacha, Tunja, and Duitama, as well as in border municipalities such as Cúcuta, Villa del Rosario, and Tumaco.

Although the deployment of army troops has not taken place in Bogotá, arbitrary detentions and disproportionate use of force by the police have already been reported. Last Thursday, Councilman Diego Cancino issued a statement denouncing that “the police are abusing the quarantine situation and committing serious human rights violations.” He referred to cases of sexual violence reported by women in Bogotá and, in particular, mentioned the case of a woman who, while walking her pet, was approached by members of the National Police and taken to a police station. There, police members locked her up, robbed, extorted, beat, groped, and stripped her naked.

If these scenarios seem extreme and fraught with violence—and perhaps alien to those reading from other places where contagion prevention measures still allow children in parks and family walks—the presence of armed and uniformed individuals acting in authoritarian ways is even more dramatic for people in dispersed and remote areas of Colombia. A week ago, an association of several indigenous communities in Chocó (a state in northwestern Colombia) publicly denounced that they are currently suffering a double confinement: that of COVID-19 and that of armed groups. Confrontations between paramilitaries and guerrillas are putting in danger the lives of 612 people in Bojayá, a municipality with a tragic history of suffering linked to the armed conflict.

Now, the confinement associated with the pandemic has come to reinforce those dynamics that people in Bojayá have experienced for quite some time. Affected communities are not demanding militarized state presence to address either of the two confinements, but interventions capable of guaranteeing the fundamental rights to peace, life, food, and health. In highly unequal countries like Colombia, events such as the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate in cruel ways that it is difficult to produce health without simultaneously seeking peace, respecting life, and ensuring the material conditions that make it reasonable for everyone to follow stay-at-home measures. As a way of addressing a public health crisis, militarization becomes a reminder that this is how the state tends to respond to critical events in Colombia in times of both war and “peace,” as the response to the national strike and protests at the end of last year attest.

Painting decorating one of the walls in the Colombian army’s Health Office. Photo by Lina Pinto García.

“Sheltered”

The assumption of home as shelter is also a troubling one. As the pandemic has laid bare the vast inequalities that sustain capital accumulation in highly uneven countries such as Colombia, homeless populations, those with inadequate housing conditions, and people who depend on informal day-to-day jobs face particular challenges for making a living. At the same time, they have been increasingly targeted by the police.

This assumption also breaks open the reality of incarcerated populations. One of the most devastating and tragic events in the context of the pandemic took place simultaneously inside several prisons in the country, where confinement creates favorable conditions for rapid contagion. On March 21, 2020, prisoners protested to call for effective containment and prevention measures against the spread of the coronavirus, especially considering that prison overcrowding is around 53%. They demanded the establishment of exceptional measures for the temporary release of pregnant and nursing women, accused individuals who have not been convicted, and people over 60 years of age. Guards used weapons and their response was marked by the violation of rights. As a result, 23 prisoners were killed, and 83 prisoners and 7 guards were injured. Downplaying the legitimate demands of the prisoners and the need for radical reform of criminal and prison policy that has been pending for decades, national authorities dismissed the protest as an escape attempt, thus legitimating the massacre. On that day, the Ministry of Health confirmed 210 cases of COVID-19 and the first death from this cause in the country. The 23 murdered prisoners were not part of the epidemiological statistics of the pandemic, but they make part of its social reality.

Lastly, as feminists have long insisted, home is not a safe place for women, children, the elderly, and LGBTQ people, for whom practicing social distancing and self-isolation often implies being locked down with their abusers. Not only does the heavy burden of care work fall on their shoulders, but gender-based violence has incremented during confinement, including femicide. In other words, being “sheltered at home” is particularly dramatic for those whose home is anything but shelter. A hotline set up by the state to counsel female victims of domestic violence has received 91% more calls than those received in the same period in 2019, which represents a 79% increase since the confinement started, following a pattern that has been recognized globally.

What lies ahead?

The events we have mentioned account for the overlap between the violent dynamics of the war, their continuity after the signing of a peace agreement, and statecraft developments in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The concomitant forms of violence that we have highlighted thus speak of the plasticity of militarization in war contexts and how it gains new strength in the name of public health and security.

What are the dangers of seeing militarization as the normal, if inadequate, way to deal with problems affecting society as a whole? What are the implications of using armed forces to respond to a public health emergency in a country that is supposedly implementing a peace agreement to overcome years of violence? Are we going to let our history of violence and militarized state presence be replicated once again, this time in the name of collective health? Isn’t this precisely an opportunity to learn an unprecedented lesson and challenge what we have come to normalize by acting on principles of care and social justice? What difference would it make in the short and long term if we resolved to handle the pandemic through radical compassion rather than militarization?

The authors thank Andrés León Araya for his comments and suggestions to a previous draft.

[1] Pseudonym.

2 Trackbacks