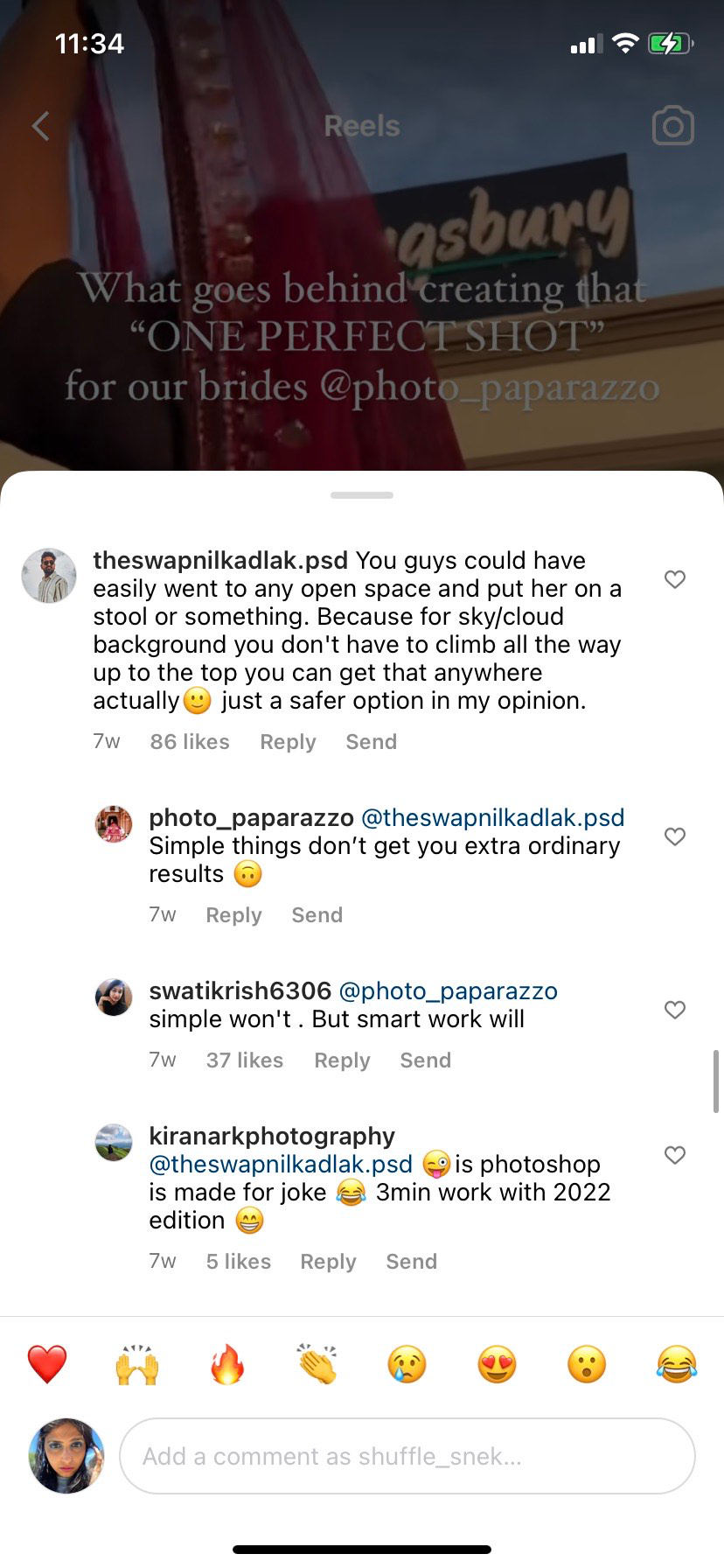

Screenshot of the comments for the post by @photo_paparazzo, being discussed in the blogpost

In an Instagram post by a photographer @photo_paparazzo, we see what the labor of creating a perfect picture looks like. The video, set to trending music, shows a woman in a bridal outfit being helped up a wooden ladder to the roof of a room on a terrace by three men. One of the men is holding a camera. Once the woman is on the roof, the photographer takes the mesh maroon-colored dupatta and wears it over his head, presumably to show the bride how to pose. The text on the video reads, “What goes behind creating that “ONE PERFECT SHOT” for our brides @photo_paparazzo.” The caption reads: “To one of the favourite parts of our job, creating EFFORTLESSLY beautiful portraits and memories for the brides to remember (cry-laughing emoji)…kudos to the team and most important each and every bride of @photo_paparazzo and being the sport of our creativity (red heart emoji).” The video ends with two stunning shots of the bride, captured in the golden yellow light from a setting sun (what is referred to as the golden hour). The video has amassed 6.7 million views, 970 thousand likes, and 1,571 comments. A cursory look at the comments reveals positive reception of the video. The comments range from the use of only emojis (fire emoji, red heart emojis, heart eyes emoji, among others) reflecting appreciation to more overt comments acknowledging and recognizing the efforts put in by the photographers.[1]

One particular comment on the post, however, deviates from this general trend and points out how the same effect could have been achieved using far simpler techniques that did not require the bride to be helped up a rickety ladder. Part of the comments reads, “You guys could have easily went to any open space and put her on a stool or something [referring to the flattering low angle shot that makes the bride appear tall while capturing her elaborate, sartorial silhouette].” The OP (Original Poster) replies to the commenter, “Simple things don’t get you extra ordinary results (upside down smiley emoji).” Another commenter adds to this discourse, “[winky face, tongue out emoji] is photoshop is made for joke [cry laughing emoji] 3min work with 2022 edition [smile emoji].”

Several threads run through this video. They include the framing of the usually hidden labor, the visual spectacle it generates, and the conversations that ensue. This blog post is an invitation to think through the structuration of social media footprints of the “real.” Instagram has emerged as a crucial, though by no means exclusive, site where the mundane and spectacular realities are audio-visually negotiated. The comment about the use of “photoshop” does not explicitly mention filters, nor does it address the concerns of the commenter who suggests that similar photographic results could have been achieved without the spectacularly framed use of a rickety ladder. It is certainly true that the use of photoshop and filters (often used simultaneously) allows for altering already produced images; and that this tool would not have resolved the problem of the angle at which the original photo was taken.

Filters have been a crucial site through which the economy of pleasure functions on social media. For the purposes of this piece, I understand filters as more than just tools that allow for editing existing images. I understand the filter as a rhetorical device that circulates in discourses about “realness” and “authenticity” on social media. While filters allow for editing and playing with the coloring, brightness etc. of existing images, I use the filter as a larger concept that includes things like Photoshop, as well as modes of manipulating bodies (posing, for instance), environments, objects, within and outside the frame, that are intentionally or unintentionally visible. Additionally, I want to engage with the frivolity and silliness that are associated with the use of filters. The silliness and frivolity directly relate to the perceptions of aesthetic presentations, especially vis-a-vis groups that have been historically marginalized due to their race, caste, class, gender, ethnicity, sexuality. The silliness of the filter plays into discourses about the “real” and “authentic” presentation of the self. Aesthetic presentations have always been a crucial site of policing bodies (Gupta 2016; Viswanath 2014) and boundaries of the self. The politics of using (or not using filters) aligns with and extends these historical dispositions.

Nevertheless, the use of terms like “photoshop” and “filter” (with its absence circulating as the popular hashtag #nofilter), to suggest the ease of manipulating a pre-existing “reality,” is crucial here. The allusion to “photoshop” becomes a playful (also indicated in the use of several emojis) admission of knowledge about how “reality” is manipulated. This comment, then, illustrates the ability of this spectator to showcase their ability to discern (even if not quite overtly police) the “reality” as well as the techniques through which “reality” is frequently manipulated on social media. Viewed in this way, then, this comment about photoshopping being an easier alternative to the rickety ladder extends the logic of the first commenter, who had also proposed the use of the stool as an easier alternative.

So, what is at stake in providing easier alternatives to filtering “reality?” I suggest viewing these comments in relation to how vanity and aesthetic presentations are generally viewed: as frivolous and silly and therefore undeserving of (too much) labor. The video posted by @photo_paparazzo, has very little to do with the bride. The purpose of the video is to visibilize the labor performed by the photographer and their team. The comments that challenge the necessity of the labor then are minimizing the labor that is being provided in the video as well as the validity of the final images. These comments, then, contest the OP’s claims of producing “extra ordinary” results. I am not interested in making objective claims about whether it would have been possible to achieve the photographs of the bride without the labor that is being made visible through the post in question. Instead, I am interested in asking why the intentionally visibilized labor of the photographer is being minimized, which effectively also minimizes the artistry and artistic vision of the photographer. Why is there a discomfort around the intentional embrace of not just intellectual but manual labor that goes into producing pictures of the bride?

Multiple assumptions about photography, artistry, and labor are being challenged by the video posted by @photo_paparazzo. For one, photography, from its inception, has been tied to the expansion of the colonial project (Pinney 1997; Ramaswamy 2002) and has become the visual “evidence” of producing the “truth” about the aboriginal and colonized populations at large. These legacies of photography producing the “truth” have continued in journalism, with one of the most popular examples being the portrait of Sharbat Gula by Steve McCurry for National Geographic. The striking photograph, with Sharbat’s piercing green eyes, becomes undisputable visual “evidence” of the “truth” about the Afghan refugees in 1984. It was later revealed that Sharbat was forced to pose for this image, revealing her face covering so the world could learn the “truth” about her and her plight. Apart from the problematic racial and gendered dynamics that structured the process of posing for this picture, the physical labor of producing the posed image must remain “hidden” for it to be considered “truthful.” Now, I am not equating the video posted by @photo_paparazzo and the photograph produced by McCurry. These photographs are produced in different contexts, for specific audiences, and reflect very different power dynamics. For one, the bride paid thousands of rupees to hire @photo_paparazzo to photograph her, implying specific dynamics of consent and control. I want to focus on the contentious comments. The arbitrary judgments about how much time and labor the photographs deserve suggest the subject matter and purpose of photography themselves are not considered worthy. The solo shots of the bride add nothing to our knowledge and “truth” about the customary rituals that guide the wedding process. These are frivolous shots of a woman taking up space without feeling the need to hide it, making light of an otherwise serious and naturalized institution: marriage. Weddings are a crucial site through which social investments are made and kinship and caste networks reproduced. They are not moments for celebrating individual choices (especially at the expense of the collective: the family and kin). Gendered labor is a crucial mode of reproducing caste (Ambedkar), it demands the invisiblized and undervalued labor of dominant caste women. This becomes an active form of devaluing their gendered selves, with their desires sacrificed in the name of “respectability” and “morality.” Caste requires women from dominant castes to uphold heteropatriarchy, and this includes taking up too much space. The comments, thus, are taking issue with the space being claimed in this post. The demand for space momentarily unsettles patriarchy, only to be swiftly told that 3 min is all the picture ought to be worth. The video is interpreted as gimmicky because it is unfathomable that there should be any interest in learning behind-the-scenes knowledge about the production of the images in question. These comments are steeped in discourses not just about gender but about caste and gender. The policing of the bodies of dominant caste women is necessary to uphold the validity of caste hierarchy.

References

Ambedkar, B.R. (2019). “Castes in India: their mechanism, genesis, and development.” In Vasant Moon (ed.), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 1(pp. 5-22). Government of India.

Gupta, C. 2016. The Gender of Caste: Representing Dalits in Print. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Pinney, C., 1997. Camera Indica: the social life of Indian photographs. University of Chicago Press.

Ramaswamy, S., 2002. Visualising India’s geo-body: Globes, maps, bodyscapes. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 36(1-2), pp.151-189.

Viswanath, R. 2014. The Pariah Problem: Caste, Religion, and the Social in Modern India. New York: Columbia University Press.

Endnotes

[1] It should be noted that comments are often closely monitored by creators (and users in general), especially by those who have publicly accessible accounts with a high number of followers. Thus, a business account like @photo_paparazzo, with 73.4 thousand followers, with posts garnering thousands and even millions in views, is likely to monitor their comments section for anything that might reflect negatively on them.

1 Trackback