The warm December sun had only recently risen over Miami Beach when I found myself in the bustling halls of Art Basel Miami 2021, one of the world’s most prestigious international art fairs. As an anthropologist and tech entrepreneur, I wasn’t there just to admire the art—though there was plenty to admire. I was there to observe and make sense of the intricate dance between artists, gallerists, and collectors in this temporary, high-stakes marketplace.

Art fairs like Art Basel Miami are annual events where galleries from around the world converge to showcase and sell their artists’ work. For a few days, the fair becomes the epicenter of the global art market, with thousands of works on display and millions of dollars changing hands. Collectors, curators, consultants, and art enthusiasts flock to these events, creating a frenzy of activity as deals are struck and reputations are made.

As I walked through the crowded aisles, the stark contrasts were impossible to ignore. The fair’s layout itself told a story of hierarchy and influence in the art world. Established galleries like Gagosian commanded prime locations near the entrance, their spacious booths bustling with activity. These high-end galleries had paid premium rates for their coveted spots, and it showed in their positioning and the attention they received. Their displays exuded an air of exclusivity, with artwork unlabeled—a silent statement that if you didn’t already know the piece, perhaps you didn’t belong.

Meanwhile, lesser-known galleries, which had paid lower fees for less prominent locations, were often relegated to the periphery of the fair. Their smaller booths, showcasing emerging artists, struggled for visibility in the sea of artwork. Visitors thinned out as you moved away from the central areas, leaving these galleries to work harder to attract potential buyers and critics.

As I left the fair, the stark contrasts I had witnessed at Art Basel—the hierarchy, the exclusivity, the struggle for visibility—resonated deeply with what I had observed in the digital art world over the past year and a half. The physical layout of the fair, with its prime spots and periphery, seemed to mirror the algorithmic hierarchies of online platforms. It was clear that the inequalities of the art world weren’t just preserved in the digital realm. In many ways, they were amplified.

Image of an art fair (generated by the author using ChatGPT)

Framing Inequality: Physical and Digital Divides in the Art Market

Much like I witnessed at Art Basel, there is a clear divide in the art world, but that was not the first time I encountered it. In fact, my journey to Art Basel started at the outset of the pandemic when I became involved in researching the digital landscape of the art market as part of a founding team in an ArtTech startup. All of us were interested in art and had heard from many in the mid-market how much they struggled with selling art online. After some initial market research, we determined that the online art market offered a compelling business opportunity, so we decided to dive deeper.

I began by conducting ethnographic research with diverse stakeholders from across the art world. This investigation led me on a multifaceted journey: from virtual interviews and observations during the pandemic to deep explorations of Silicon Valley’s intellectual property and algorithm-driven culture, and eventually to Art Basel itself. Throughout this process, I encountered numerous stories highlighting the stark disparities in the digital art world, mirroring those I would later witness at Art Basel.

One such story came from Maria, a talented photographer I interviewed during this early research phase. Maria wasn’t showcased at Art Basel Miami—in fact, she was precisely the type of artist who struggled to gain that level of recognition, much like those relegated to the periphery of the fair. Her large-format seascape photos had earned her a devoted local following in a small town, far removed from any established art scene. Yet, on major online platforms, her work was lost in a sea of more established names. “It feels like shouting into the void,” Maria told me, her frustration palpable. “I know my work resonates with people when they see it, but how can they see it if the platforms don’t show it to them?”

Maria’s struggle, while personal, was emblematic of a broader trend I observed among mid-market sellers. Many faced similar challenges. Without established credibility—be it name recognition, gallery or museum shows, or a history of public sales data from auctions—they found it nearly impossible to gain significant traction on digital platforms. These platforms seemed to cater best to two extremes: high-end established artists who could command premium pricing, or very affordable hobbyists. Those in the middle, like Maria, were left struggling to be seen or earn a living.

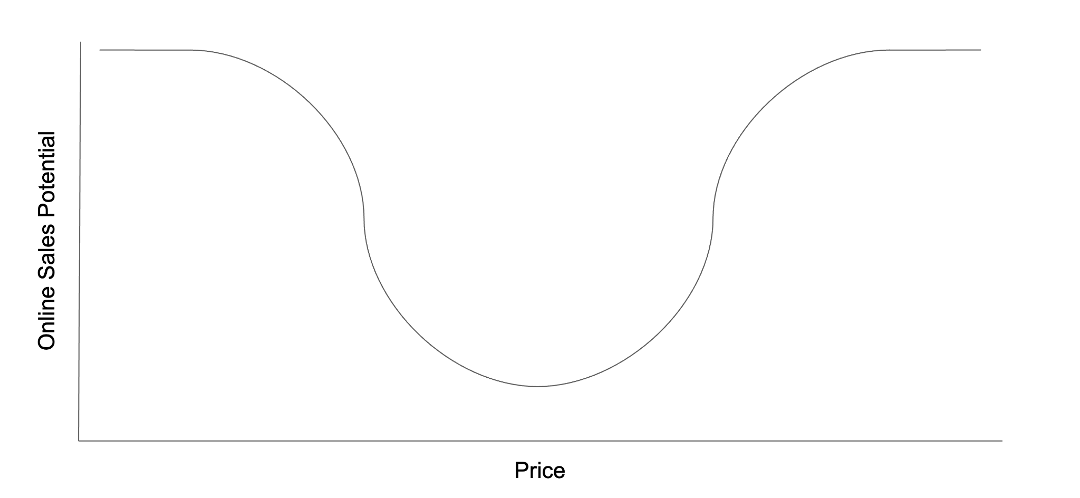

Graph depicting the relationship between online sales potential and price. Graph made by author.

While Maria’s story highlighted the challenges faced by talented but less-connected artists, another interview revealed the flip side of this dynamic. In a conversation with a gallerist from a major city, the role of capital in shaping artistic success became apparent. He shared a revealing anecdote about an artist he knew, one who wasn’t exceptionally skilled but came from a wealthy family. This artist’s family had the resources to buy their way into recognition. They paid for glowing reviews and features in local art publications, manufacturing buzz that eventually caught the attention of influential tastemakers. Now, this artist is considered “up-and-coming,” and their work sells for significant sums.

These contrasting stories struck me not just for their illustration of how challenging the art world can be in the mid-market but also for revealing the outsized role of various forms of capital in shaping art careers. Moreover, they hinted at how these dynamics, long present in the physical art world, were being intensified and accelerated in the digital realm, setting the stage for a deeper exploration of the algorithms behind the recommendations.

From Insights to Innovation: Reimagining Recommender Systems

The stories of Maria and the gallerist not only highlighted the role of capital in shaping art careers but also pointed to a crucial issue at the heart of the digital art world: the amplifying effect of recommender systems on existing inequalities. These algorithmic systems, which suggest content to users across various platforms, have become ubiquitous in our digital lives. From music streaming services to social media feeds, recommender systems silently curate our online experiences, ultimately governing the success or failure of producers in the creator economy.

My research revealed how these digital platforms, despite their initial promise of democratizing the art world, often reinforced and even amplified the existing hierarchies and inequalities I later witnessed in physical spaces like Art Basel. This digital entrenchment of inequality emerged as a key challenge that demanded innovative solutions. This is because the algorithms powering these platforms tend to favor artists or gallerists who already have name recognition, a significant following, press, positive reviews, or a history of sales. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where popular art market participants become more visible, leading to more sales and recognition, boosting their visibility even further.

At the core of this cycle was the crucial role of capital in mediating success in recommender systems. An artist or gallery’s ability to thrive in this landscape was heavily influenced by their access to various forms of capital—economic, social, and cultural. Financial resources allowed for investment in paid promotions or even manufactured press coverage to boost visibility and name recognition. Strong social networks and cultural capital also provided a head start in building a following and credibility, amplifying discoverability within algorithmic systems. Notably, this advantage often persisted irrespective of the intrinsic quality of the work. Conversely, talented artists and exhibitors lacking these forms of capital found themselves at a significant disadvantage, struggling to gain the initial visibility needed to break through the algorithmic barriers.

These insights called for a radical reimagining of how recommender systems could work in the art world and beyond. Drawing directly from the ethnographic research, I set out to design a system that could level the playing field. The result was a machine learning model based on the concept of “behavioral capital,” a novel approach to addressing the systemic issues in recommender systems.

Instead of relying solely on traditional metrics like popularity or existing reputation, this new model would recognize and reward users’ labor and contributions to the community. The system considers factors such as engagement with other users’ work, constructive feedback provided, and overall participation in the platform’s ecosystem. This approach aimed to give artists like Maria a fair chance at visibility, regardless of status, relationships, or resources, while also attempting to foster a positive community.

While not a perfect solution, as no algorithm can entirely erase deep-seated societal inequalities, this approach exemplifies how anthropology can contribute to addressing real-world issues of power and capital. It demonstrates anthropology’s capacity to move beyond critique, actively challenging the status quo and reimagining existing power structures.

Anthropological Praxis: From Critique to Creation

This example illustrates a broader opportunity for anthropology to not just identify problems, but to actively participate in developing solutions. This shift from observation to intervention is particularly relevant as the discipline grapples with its role, relevance, and impact in the 21st century. The upcoming American Anthropological Association’s 2024 Annual Meeting, with its focus on the theme of praxis, provides a timely platform for this discussion. While the conference rightly emphasizes applying anthropological insights to address systemic injustices and reimagine our discipline, there’s a noticeable lack of acknowledgment for anthropologists working in business. This is a missed opportunity. We ought to approach praxis holistically and recognize the full spectrum of anthropological contributions, including those in business settings.

As Lora Koycheva and I discuss in our edited volume, EmTech Anthropology, working at the intersection of anthropology and business allows anthropologists to transcend critique and become innovators capable of reimagining and reshaping technologies and industries. Further, the jobs in business are plentiful, and many of my colleagues have found they are able to do well while doing some good, a welcomed opportunity given the state of higher education.

By embracing this broader view of praxis, the AAA annual meeting could foster a more inclusive and impactful anthropology that bridges academia and industry, theory and practice. It’s through such engagement that we can truly embody the conference theme and reimagine our collective future.

As for me, the sun has long since set on that day at Art Basel Miami, yet it serves as a vivid reminder of the importance of anthropological intervention. Reflecting on this experience, I am encouraged by the opportunity to move beyond the dominant anti-solutions narrative and contribute to shaping digital futures, however imperfect they may be, for if we anthropologists are not there, who will ensure the human stories are not lost in the code?