Tomorrow, November 20th, the world will commemorate Transgender Day of Remembrance, a day to collectively mourn and remember those who have died as a result of transphobia. Started in 1999 by US trans woman Gwendolyn Ann Smith, Transgender Day of Remembrance is now observed in countries around the world, including my primary field site, Chile.

In this post, I explore how social media might be understood as a technology of memorialization and mourning, especially for marginalized groups. Inspired by informal roadside shrines called animitas, popular in Chile and elsewhere in Latin America, I propose the ‘networked animita’ as a useful analytic for understanding trans remembrance online. I do so through an exploration of the digital afterlife of Chilean trans activist, educator, interlocutor, and friend Mara Rita Villaroel Oñate.

The Networked Animita

The word animita is a diminutive form of ánima, an old Spanish word meaning ‘soul,’ itself from the Greek for ‘breath.’ These usually simple, church-shaped shrines are customarily erected in the physical location of a particularly tragic, sudden, or untimely death. Historically, this is because of a belief that the souls of people who have died in this manner remain temporarily trapped between the worlds of the living and the dead, and should be kept company. While the grave is where the body is laid to rest, the animita is where the soul—the breath—of the tragically deceased resides, offering a conduit of communication that at once connects and neatly separates the living and dead (Turner 1974).

A typical animita.

Animitas are usually erected and maintained by family members and friends of the deceased, adorned with photos, cherished possessions, flowers, and letters. However, in many cases, these animitas take on a life of their own, transforming the deceased into a folk saint—to whom prayers, offerings, and pleas for intercessions (mandas) can be offered—often at the cost of effacing the specificities of the life originally being commemorated.

The practice of building and maintaining an animita draws on pre-conquista Andean mourning practices. These practices framed death as a transition rather than an end point, seeking to “make the deceased into an ancestor” who will come to mediate relations between the physical and spiritual planes (Readi Garrido 2016). As such, the animita must also be understood as an archive of cultural and religious syncretism resulting from centuries of Spanish colonization. In addition to religious iconography, it is not uncommon to see stuffed animals, fútbol paraphernalia, photos of pop culture figures, cigarettes, and other seemingly non-religious symbols inside and adorning the structures.

But animitas are also spaces of communication both with and about the dead. They provide a physical location outside the cemetery at which friends, loved ones, and well-wishers can gather with their communities to remember and commune with the deceased. And with the popularization of social media in Chile and worldwide, many traditional mourning practices have moved at least partially online.

As such, I define what I have termed the ‘networked animita’ as the assemblage of social media profiles, posts, pages, content, and media that are linked thematically by a particular death, and often literally linked through their underlying code. Its digital nature allows those who may be far away or less directly connected to the deceased to participate in mourning practices, what Anna Wagner has called “social expansion” (2018). Moreover, just like the traditional animita, the networked animita also constitutes a space in which subjectivities are reconstituted and renegotiated: the deceased as the object of veneration and debate, and those who interact with the animita as mourners with certain expertise and responsibilities, despite varying levels of connection in life.

The Death of Mara Rita

On April 19, 2016, trans activist, teacher, and author Mara Rita Villarroel Oñate died unexpectedly of an aneurism, having just turned 25. Unfortunately, untimely and sudden deaths of trans women and travestis in Chile (and globally) are not uncommon (Campbell 2019). Due to familial and societal rejection, they are often forced into precarious lives that put them at higher risk for homelessness, sexual and domestic violence, drug abuse, and premature death (Valentine 2007; Kulick 1998; Rodríguez 2013). However, despite her family’s working-class status, Mara did not experience the immediate precarity of many of her peers. She attended a prestigious Catholic high school, and was admitted to the equally prestigious University of Chile to study Spanish literature and high school pedagogy. Nonetheless, having entered the university as a legal male, Mara was barred from doing her student teaching until such a time as she was deemed “feminine enough” to “pass” as a cis woman in the classroom.

Almost immediately after her death, friends and acquaintances familiar with the treatment she had received at the University of Chile began to speculate that the cause of Mara’s death was an overdose of the hormones she took as part of her biomedical transition, an attempt to speed up the results. Nonetheless, there has never been any official evidence of this, and those closest to Mara maintain that she was meticulous and exact with her medications. The “truth” of this matter is ultimately unknowable, and I make no claim to know it. Rather, this post focuses on the competing discourses surrounding Mara’s death, illustrating the iterative and contradictory processes of resubjectification —a collective renegotiation of the subjectivity of the dead facilitated by the networked animita.

Conflicting narratives and resubjectification

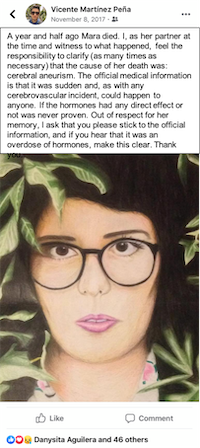

On November 8, 2017, Mara’s former boyfriend Vicente made a brief Facebook post, accompanied by a drawing of Mara’s most famous image, the one that appears on the back cover of her poetry book Tropico Mío (2015). Inspired by the ongoing debate about Mara’s death, it pushes back against the idea that Mara would have knowingly used hormones in a dangerous way. As will become clear below, he felt that this was an ethical obligation given Mara’s high visibility in the community. However, the post also positions Vicente as an expert, and perhaps even a proxy for Mara, a role in which he increasingly found himself. His post makes clear that he, and no one else, witnessed Mara’s death from the first sign of trouble to her last breath, and that this experience allows him to speak with more certainty and authority than other members of Mara’s social circle and the movement at large. Perhaps most importantly, Mara’s subjectivity as a “responsible” trans person—or not—became central to this debate.

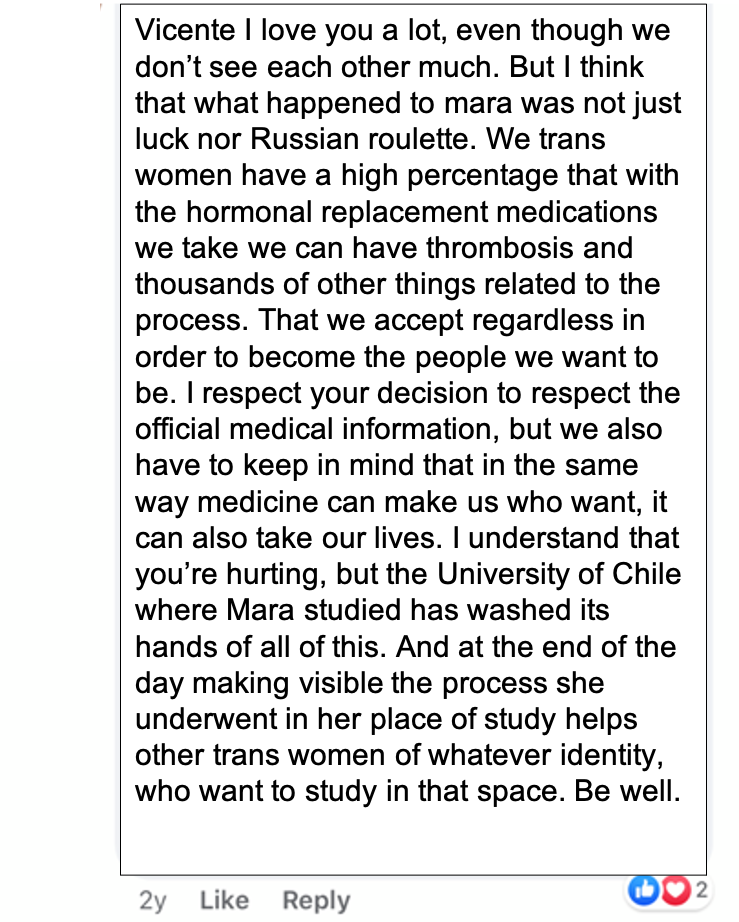

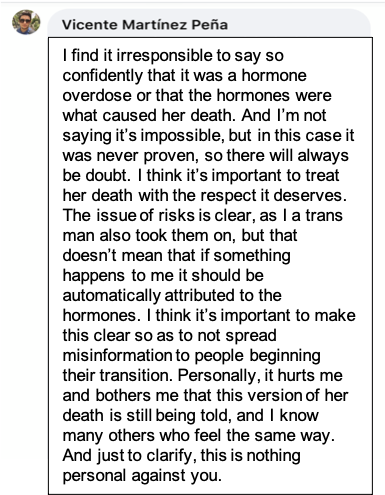

Unsurprisingly, Vicente’s post received quite a bit of engagement, as well as a few comments that evince the role of the networked animita in constituting and reconstituting both the deceased and the mourning. For example, a comment from another transfeminine activist offered the following:

Ultimately, her post lays the responsibility at the feet of her university, positing that sharing Mara’s experience at the University, regardless of the absence of biomedical “proof,” is nonetheless important to the cause of trans rights Mara held so dear. Here we see the reconstitution of Mara as an activist first and foremost, one who was dedicated enough to her cause that the details of her death are less important than the context surrounding it. That is, regardless of the actual cause of Mara’s death, the University of Chile is at least partially responsible, due to its transphobic policies. As such, the politically astute and ethical narrative is one that improves the treatment of other trans people in her position, regardless of the details.

In his response, Vicente positions his ethical responsibility toward the trans community differently from that of the commenter above. As a trans person himself, Vicente is personally acquainted with the benefits and risks of biomedical transition, having witnessed them in his own body and Mara’s. He argued that—especially because of Mara’s prominent place in the trans community—presenting suspicions as fact was dangerous for those beginning or considering biomedical transition. He worried that this discourse might discourage people from making free and informed choices about their transitions.

These exchanges demonstrate the iterative and fraught process of constructing a lasting subjectivity for the deceased through engagement with the animita, one that relies as much on the memories, experiences, and political commitments of others as it does on any particular objective reality. However, the networked animita also lays bare the processes of resubjectification of certain mourners, like Vicente, as both experts in the legacy of the deceased and as actors with an ethical obligation to their memory. While this is certainly also the case for mourners at physical animitas, the particular archival nature of social media makes this process particularly clear. Nonetheless, it is also important to understand how Mara’s own social media accounts—active long after her passing—also fulfill this function.

Temporality and Subjectivity

The comments left on Mara’s personal profile and fan page (for her literary work) are different from the conversations referenced above, in that the discourse on these pages takes the form of a direct conversation with the deceased, one that paradoxically often overtly marks the absence of the deceased while still engaging in direct communication. This communication is in many ways directly analogous to the kinds of direct communication that happen around physical animitas, in the form of prayers, mandas, written blessings, or conversation that mirrors mourners’ previously established conversational patterns with the now-deceased.

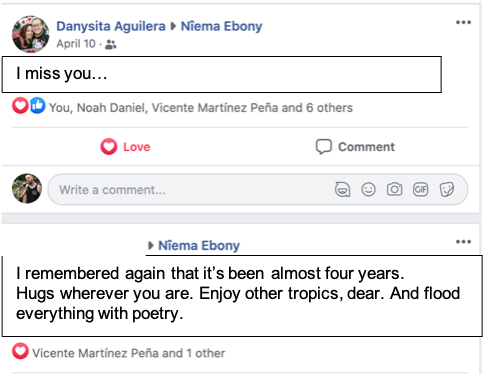

The animita, both the physical version and its networked analogue, is characterized by multiple overlapping temporalities that might in other contexts be understood as mutually exclusive. For example, one common mourning practice across Facebook is that of marking the anniversary of the death with posts that seem to communicate directly with the deceased. These posts from 2020 are both written in the 2nd person, directed at Mara. The first, written by Mara’s close friend Daniela, says simply “I miss you…” (te extraño), a common sentiment for those who have lost loved ones. The post below begins with the author overtly marking the passage of time since Mara’s death, and then wishing her well “wherever [she] may be.” Finally, she asks Mara to “flood everything with poetry.”

At first, the very idea of a commemorative post seems to reify Mara’s death, a final end point to her linear journey from birth to death. However, from another perspective, it is precisely the act of commemorating Mara’s death that brings her—momentarily—back into the world of the living. We can read ‘missing,’ especially followed by an ellipsis, as colored by some hope that the ‘missing’ will cease, though it may remain unclear how and when; while Daniela is not religious, she would often make comments about Mara penando (haunting) her house so that we wouldn’t forget her. Similarly, the second poster’s use of the subjunctive mood marks uncertainty about Mara’s exact whereabouts, but the words that follow hint at Mara as an agentive force.

Posts like these complicate binary, linear understandings of mortality; if death is truly final, to whom is the message directed? However, the networked animita, like its traditional analogue, is a space of temporal collision, in which a loved one can be simultaneously absent and present. The networked animita creates a space of communal mourning, one that makes possible utterances and interactions that in other contexts would be nonsensical. This space at once resolutely tied to the unequivocal death of a human—without which the animita would not exist—and one that exists outside linear time, in which death is not always the opposite of presence. Paradoxically, it is the march of linear time, leading up each year to another April 19th, that encourages the ritualistic return to this space of temporal chaos. It is in the remembering that Mara is no longer present that she is made present.

Conclusion

In this post, I have endeavored to demonstrate how social media technologies have fundamentally changed the character and quality of our interactions, even after death. While the animita has always provided a space for public mourning, the networked animita permits the visualization of these collective and sometimes contradictory acts. Moreover, I hope to have shown the potential of the inherent archival qualities of certain social media technologies to better document and understand practices of mourning and our relationships with the dead and dying. Through ethnographic engagement with these practices and dynamics, we can better understand cultural shifts in attitudes toward mortality, while also remembering and celebrating the many trans people whose lives were taken by transphobia, through both their own archival traces and the memories of those who remain. Mara’s death, though not the consequence a transphobic attack, was indisputably hastened by the climate of transphobia and ignorance that permeates much of the Chilean medical system. In the networked animita, both Vicente’s retelling of Mara’s final moments and the responses it provoked bring this reality to the surface, resisting its elision into a narrative that frames Mara’s death as either a tragic accident or as her own fault, highlighting instead the societal factors that hastened it. Rest in peace, Mara.

My deepest thanks to Noah Pozo Gutiérrez, Mara’s friend and mine, for his help editing the Spanish of this post.

Campbell, Baird. 2019. “Transgender-Specific Policy in Latin America.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press.

Kulick, Don. 1998. Travesti : Sex, Gender, and Culture among Brazilian Transgendered Prostitutes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Readi Garrido, Pía. 2016. “Origen e Historia de La Animita.” In Lecturas de La Animita: Estética, Identidad y Patrimonio, edited by Claudia Lira, 17–26. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile.

Rita, Mara. 2015. Trópico mío. Santiago, Chile: Mago Editores.

Rodríguez, Claudia. 2013. Cuerpos Para Odiar. Santiago, Chile: Self-published.

Turner, Victor. 1974. Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Valentine, David. 2007. Imagining Transgender : An Ethnography of a Category. Durham: Duke University Press.

Wagner, Anna J.M. 2018. “Do Not Click ‘Like’ When Somebody Has Died: The Role of Norms for Mourning Practices in Social Media.” Social Media and Society 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117744392.