Recently I had the pleasure of attending an exciting new film festival called Ethnografilm, a showcase of ethnographic and academic films that visually depict social worlds. Helmed by the festival’s Executive Director Wesley Shrum (Professor of Sociology, Louisiana State University), the event took place April 17-20 at Ciné XIII Théâtre, a unique venue in the Montmartre district of Paris.

The variety of films was indeed impressive, and ranged from old-school anthropological investigations of “disappearing worlds” to animations that stimulated the eye and illustrated interactive tensions in visual forms. Despite fears about the disappearing anthropologist filmmaker, it was interesting to see that Jean Rouch’s classic film Tourou et Bitti (1971), which was screened on Saturday night, played to a packed house! Given that co-sponsors included the International Social Science Council and The Society for Social Studies of Science, it is perhaps not surprising that the festival included many technology-related films. Themes included both opportunities and tensions in areas such as online interaction, ethics, “primitive” technologies, and high-tech bodily enhancements. Below I profile a few of the films I was able to screen.

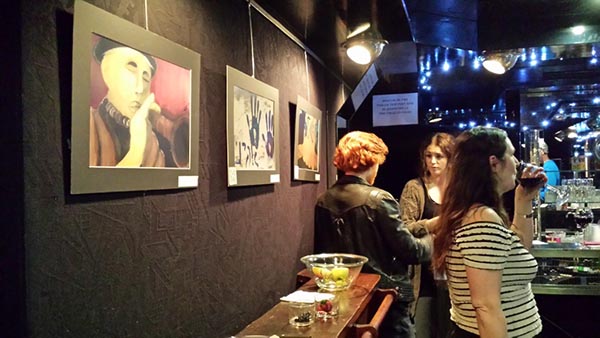

It is impossible to proceed without saying a word about the Ciné XIII Théâtre itself, as it became one the stars of the festival! From its descending stairways and cozy salons to its red couches in the main screening room, the venue provided a delightful, historic, and uniquely artistic space for showcasing new films. After each session, filmmakers were invited to retire to an adjacent salon, alternatively named the “Argumentarium” to continue the conservations about the films. According to our festival program, Director Claude Lelouche bought the cinema in 1983 to use as a set in a 1920s-era film about Edith Piaf. Lelouche’s daughter Salome now runs the theater’s programming. As a special treat, filmmakers were presented with a photograph of original artwork created by students from the Lee Magnet Academy of Baton Rouge, Lousiana, which partnered with Ethnografilm. Each art piece was inspired by a screen shot from one of the films. Led by Susan Arnold, Director, Art for Film Program, Lee Magnet Academy, the art adorned the walls of the festival, which set the tone for a richly immersive creative experience.

Two films, Told You So (10 minutes; Cindy Hsieh) and Humanexus (13 minutes; Ying-Fang Shen) included reflections on some of the tensions that have been observed over the years in online spaces of interaction. Told You So takes a longer trajectory and examines a range of media from the alphabet to television to online interaction to explore pleasures and tensions that emerge across a medium. Archival footage is interwoven to tell the story of technological inflections on communication patterns.

Humanexus uses a very different modality—animation—to explore how humans try to connect through media, and often wind up feeling more alone. The message of the film appears to resonate with Turkle’s Alone Together in its expression of concerns about computer-mediated isolation. The film includes the voices of people speaking many languages yet asking the same question, which is “Is this what we want?” The film’s animated visuals provide a contrast to the more traditional types of anthropological and sociological investigations of interaction. Humanexus depicts people initially communicating in mediated ways but also being ultimately trapped in isolated boxes of their own mediated design. These images reminded me of earlier discussions of online connectedness, isolation, and forms of monadism that were discussed in the now oft-referenced Benedikt volume Cyberspace: First Steps (1991).

My film—Hey Watch This! Sharing the Self Through Media (57 minutes)—similarly addresses computer-mediated interaction and its effects. It explores online communication, community, and digital legacies. The film uses YouTube as a lens to portray trajectories of online sites. It depicts the rise and fall of YouTube as a social media site, and discusses how tensions often prompt digital migration to other sites. The film also investigates how people learn to deal with numerous alternate versions of the self that are created in images, text, and videos. When our images are manipulated in unfortunate ways, this can cause distress. Hey Watch This! provides a glimpse into an aspect of posthumanism in which our increasing connectedness sometimes results in anxiety as people cannot control the unfortunate manipulation or unbridled circulation of their alters. While YouTube is the touchstone that anchors the discussion, the film contains a broad array of themes such as responsibilities toward viewers, digital migration, and hopes for our digital legacies, an exploration that connects our past to our future(s), digitally.

Socializing at Ethnografilm Photo by Tami Blumenfield

Two films that might be paired nicely across a semester in classroom screenings represent complete opposite ends of the technological spectrum. While one shows people yearning for the past, the other explores current technological dreams/nightmares that will quite likely intensify in the near future. The first is Primitives Among Us (48 minutes; Jon Smith). It depicts the modern “primitive skills movement” in which people strive to master stone age technology and wilderness survival skills. It is perhaps not surprising that people enter into this space of discovery for widely different reasons. Some feel that in the coming days potential disasters and dwindling resources will require people to know how to live off the land. Other participants wish to find a sense of self-actualization by connecting with increasingly forgotten skills such as building fires, hunting, knapping, and basket weaving. Some participants wish to connect with these techniques and bring them into contemporary forms of art and craft.

The participants in the primitive skills movement struggle to define their participatory space, with some rejecting words such as “abo” which is evocative of Aboriginal Australians, because they are concerned that such terms are pejorative. Some reject the term “primitive” as well. To the anthropologist’s eye, folks in this movement are not rejecting technology whole cloth, but rather certain forms of it that, as argued in the film, lead to a disconnectedness to Earth and thus give rise to throw-away culture. Participants strive to make things using natural materials. For example, some people make clothes using animal hides, which arguably yield materials that last far longer than cheaply fabricated clothes such as t-shirts and jeans.

A veteran of the movement who has lived off the grid without electricity and indoor plumbing for many years argues that this sense of connectedness returns when one can see the effects of one’s actions on the Earth. If you cut a tree to make a bow and arrow, she explains, you see the stump. Each action along a chain of events keeps one connected and grateful for the Earth’s bounty. With a sense of connectedness comes respect, gratitude, and most importantly, a feeling of protection. This feeling of protection is lost amid contemporary technologies that separate people from the effects of their use of technology.

At the opposite end of the spectrum was the film Fixed: The Science/Fiction of Human Enhancement (60 minutes; Regan Brashear), which discusses the radical technological innovations that are being explored to create new forms of humanity. These technical interventions span the gamut from the needs of the disabled to the transhuman desires of those who dream of being “better than human.” Interweaving a complex and nuanced tapestry of themes, the film tackles head on important debates in human enhancement, which inevitably include ideas about identity, desire, and economics. Disabled interviewees wonder why so much is being spent on potentially eugenics-inflected technologies to create superhumans when many crucial needs in disabled communities–such as access to healthcare and public buildings, as well as reliable devices such as wheelchairs that work in the rain–remain futuristic fantasies.

I was particularly moved by the story of a man who had lost his legs due to frostbite in a climbing accident, and was outfitted with advanced prosethetic legs that considerably extended his functionality. At present he has achieved far greater heights (literally!) in his climbing and he looks forward to a future in which he has greater mobility than other older folk that will be his age. He would not ask a fairy with a magic wand to bring back his old legs, he says, as he felt that his new legs are now his in every way—including physically, psychologically, and emotionally. The film’s accessibility and rich themes would no doubt spark discussion in science and technology studies classrooms, as well broader educational contexts.

Dealing with the ongoing struggle of ethics in science, the film Dear Scientists… (26 minutes; Ioanna Semendeferi) uses artistic techniques such as the symbolic figure of Clio, the muse of history, to arouse emotion rather than invoke logic to appeal to scientists to think about crucial ethical issues regarding the processes and outcomes of science and technology. In a provocative departure from the ethnographic genre, the film draws on actors portraying scientists and acting as masked figures that raise questions about past and contemporary realizations of ethics in science. The film is the first part in a planned series which will deepen exploration of these questions. The film is principally aimed at scientists to stimulate their concern and understanding about the importance of ethics in scientific practices.

Wesley Shrum, Susan Arnold, and Greg Scott Photo by Tami Blumenfield

Ethnografilm was an amazing event. It was truly an honor to screen my film in the inaugural year of this festival. Special thanks to Wesley Shrum for his vision and tireless organizational efforts. Thanks also to the entire Ethnografilm crew for helping to realize such an ambitious and gratifying experience. Billed as a “filmmaker’s festival,” one of the great pleasures of the event was being able to talk about each other’s films and gain new insights into filmmaking and human interaction. It was truly pleasurable to involve both academic and filmmaking perspectives in tackling complex material and exploring a rich range of themes. Of interest also were the works in progress and experimental pieces that were screened; these films encouraged rich interactions and discussions. Ideas for next year include potentially expanding the number of such works shown, to facilitate practical mentorship and exchange between peers.

In sum, the venue, the films, and participants’ enthusiasm came together to produce a very rewarding experience. It is the type of festival that inspires one to make another film, in part so that one can come back to Ethnografilm next year! This is definitely an event to watch.

À l’année prochaine!

More information about Ethnografilm may be found here.

A list of films is located here.

You can also download the final program.

Ethnografilm also maintains an Ethnografilm YouTube channel with videos of statements by filmmakers.

1 Comment

I was just informed that my film and my comments will be published in the first issue of the Journal of Video Ethnography. I am extremely grateful for this opportunity. Thank you!