Content and Trigger Warning: This post contains commentary and reflections about disordered eating.

Food(ie) Fixation

In September 2019, I responded to an advertisement by a Dutch university for a PhD student interested in the policy and societal aspects of food waste valorisation. With a strong interest in sustainable food systems and an academic background in food supply chains and regulatory affairs, I seemed to fit the bill. I had not studied food waste before, but I felt a strong moral connection to the subject and the idea of investigating ways to better utilise food waste as a resource appealed to me. Following a successful interview, I was appointed to work on the project for a period of four years.

In the months that followed, I dove head-first into literature on food waste. I learned that one third of all food produced on the planet ends up as waste while one in three people go to bed hungry. I also learned that the environmental consequences of food waste are dire: distending landfills, collapsing ecosystems, depleting natural resources, among others. The seriousness of the issue stunned me, and I often found myself thinking about food waste in a personal context next to an academic one.

Mission Zero Food Waste

I have always been a careful grocery shopper, a thrifty cook, and a conscientious eater. I rarely bin food, cooked or otherwise. I attribute this to growing up with my mother’s strict ‘no food waste’ policy and my cultural background wherein wasting food borders sacrilege. Although living in the Netherlands put some distance between me and these cultural and familial contexts, I seemed to unwittingly hold on to them. Despite this, all the literature I was reading made me wonder if I was doing enough as a consumer. Knowing more made me want to do more. It made me want to make stock from vegetable scraps, smoothies from fruit pulp, and compost from compostable stuff. It also made me consider lifestyle changes such as actively planning my meals around wilting produce, purchasing about-to-expire food products when it’s possible to eat them in time, and implementing a first-in-first-out system in my pantry. And so, I set off on mission zero food waste: a fun personal project with a side of socio-environmental benefits.

Veggi Pasta made by upcycling ‘ugly’ vegetables. I experimented with several brands that incorporate food waste and surpluses in their products. (Photo by the author)

Of course, I knew that this would be a drop in a vast ocean and that the problem of food waste stemmed from complex systemic issues that cannot be solved through consumer resolve alone. But there was surely no harm in trying to be a more responsible consumer and ‘walking the talk’ as I worked towards my doctorate.

In the Belly, Out of the Bin

Being a food-waste-conscious consumer taught me a lot. It led me to knowledge which I could not have discovered through scientific research alone. It fueled my creativity, and it helped me embody my work in a deeply meaningful way.

Living alone made things easier and more difficult at the same time. Without having to worry about the dietary or gastronomic preferences of a flatmate or partner, I was free to calibrate my cooking and eat however I pleased. But it also meant that I had to eat through family-sized portions of perishable foods—a regular feature in Dutch supermarkets—all by myself.[1] Also, living alone meant that no one was observing my day-to-day interaction with food or moderating my domestic experiments, making it hard to spot unhealthy eating patterns. I was selective in what I shared about this personal project with friends and family. I occasionally mentioned a dish I had crafted from leftovers or the success of a save-the-expiring-products grocery shop. But I refrained from sharing the true extent of my involvement because I did not want to be seen as someone who was obsessed with their research.

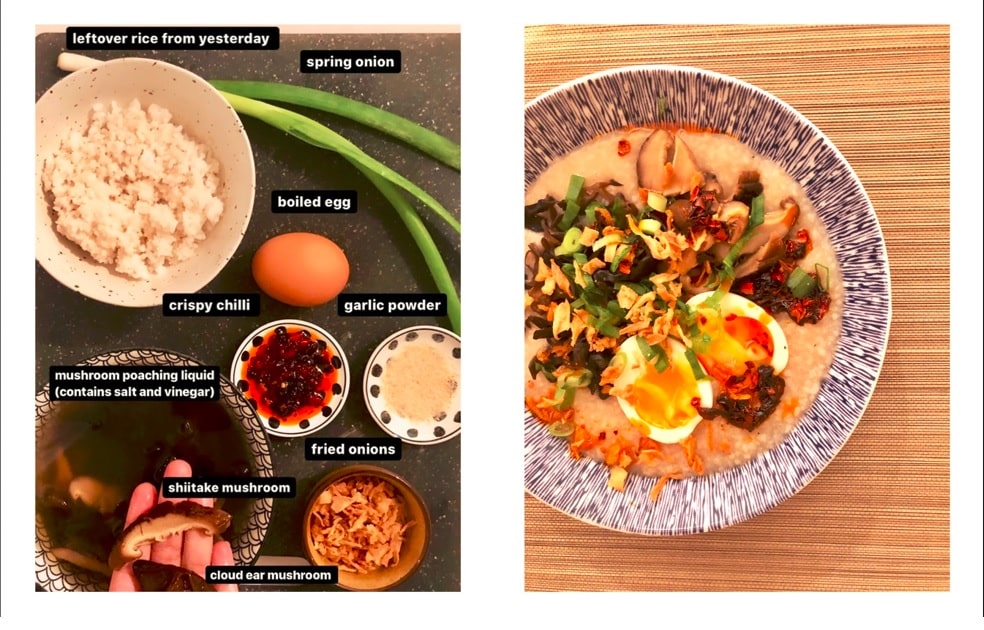

Congee made from leftover rice. Images downloaded from my Instagram story archive. (Photo by author)

The first outward sign of my new lifestyle was my weight gain. I was eating erratically and often excessively in an attempt to avoid wastage. The gain wasn’t tremendous, but I could feel my clothes fitting me more snugly than before. I also found myself taking more risks with food safety. I had become adept at ignoring rancid smells and increasingly comfortable with cutting off mouldy bits before consuming a visibly deteriorating product. These developments concerned me but not enough to pause and reflect. If food was going in my belly, it was staying out of the bin and that was a good thing.

My wakeup call came nearly a year into experimenting with food waste hacks. At a celebratory dinner with friends, I found myself plotting to finish off leftovers at a restaurant that did not allow take-away bags. There was a lone dumpling, a chunk of glazed pork belly, some stir-fried greens, and a few ladles of greasy broth. My distended abdomen and lack of appetite told me that I was full, but I knew I’d feel guilty if the food was wasted. Just as I was about to pick up the dumpling with my chopsticks, one friend remarked that she regretted ordering so much. Then, another friend said something that shocked me: “It’s alright, we have Madhura with us. She has a bin for a stomach.” The callous remark was made in jest, but it hurt me. I ate the dumpling I was about to pick up but nothing else.

A WhatsApp Group for One

In the days that followed the dinner, I was deeply contemplative. I reflected on my eating habits and ruminated over how guilt had become a driving factor in my relationship with food. I resisted the urge to look up literature on the subject because I did not wish to self-diagnose an eating disorder. I felt that pathologizing my condition, without possessing the required qualifications or expertise, would only add to my sense of shame and defeat. Instead, I resolved to work towards eating normally again: towards finding joy and fulfillment in eating good food instead of only eating to avoid food waste. I promised myself that I’d monitor my eating and seek help if things didn’t improve in a month’s time.

I started journaling every day before going to bed. I had a lot to say in the first week, but it got progressively harder to keep track of the various meals I ate in a day and my feelings connected to them. A physical journal turned out to be cumbersome, so I started exploring digital options. I was looking for an online platform that would offer privacy and convenience while letting me jot down my reflections on the go.

On the 15th of February 2021, I created a WhatsApp group with me and my partner and removed him from it seconds after. This resulted in a WhatsApp group for one—a chat where I could send messages to myself. I named the group ‘FFT,’ short for food for thought. Sending a message or two a day on FFT became part of my daily routine. I described what I ate, whether I had planned the meal around avoiding waste, and if I had stopped eating once I was full. Some messages described what I had not eaten. For example, “Today BK brought pie for everyone at work. I ate one slice but did not offer to help when she asked if someone could finish the last slice.” I frequently shared pictures of what I had eaten and sometimes of what I had resisted eating. I documented occasional wastage through pictures and wrote messages about how I felt about it.

The aftermath of a tiramisu binge. Image shared on the FFT WhatsApp chat, accompanied by a voice note describing my fears regarding the tiramisu spoiling if I did not finish it. (Photo by the author)

Once every two weeks, I would go through a fortnight’s worth of messages, voice notes, and images, conducting a brief and informal analysis. I would check for progress, take note of any hiccups, and gauge how much I needed to eat to achieve satiety. Reflecting on my relationship with food through this WhatsApp group felt therapeutic and gave me a sense of control over my situation. It allowed me to continue living a low food waste lifestyle and prevented me from taking extreme measures or feeling guilty. It also helped me deliberate on the limitations of individual efforts to reduce food waste and refocus my attention on systemic political and economic issues that allow excessive production in the first place.

I did not create the WhatsApp group with the intention of undertaking an autoethnography project. I did not think of it as research at all. Plus, messages sent on a WhatsApp group sounded too frivolous and inconsequential to be considered data of any kind. But reading the work of Dunn and Myers (2020) made me reconsider this. They underscore the importance of digital connectivity in our lived experiences and push for digital autoethnography to be recognised as a legitimate methodology in a time when “our days begin and end with screens.” Atay (2020) suggests that as everyday life becomes more digitalised, our identities and realities are increasingly shaped by digital mediation. Consequently, our identities are a blend of cyber experiences, narratives, and mediated representations. To study these experiences, they advocate for the use of a narrative-based digital approach—a form of autoethnography that can be employed for examining our physical and digital selves within our heavily digitalised media environments. The works of Dunn & Myers (2020) and Atey (2020) helped me recognise that my use of a WhatsApp group to analyse my lived experiences was indeed a form of digital autoethnography. And that it brought me back from the brink of disordered eating.

What Now?

I stopped using FFT in May 2022. By March 2022, I was confident that my eating habits had reverted to normalcy. My messages on FFT rarely mentioned instances of overeating to avoid food waste, I wasn’t taking food safety risks, and my portion sizes and meal intervals had gone back to what they were in 2019. Reducing food waste is still important to me but it does not dictate my relationship with food. The chat, which I have now archived, is a treasure trove of over 500 messages that trace my journey from disorder to order. It is a reminder of how reflecting on my own experiences of avoiding food waste shaped my research and my outlook towards my PhD trajectory. FFT helped me look at the ‘bigger picture’ and investigate how powerful stakeholders such as supermarkets and institutional actors like policymakers could make things easier for consumers willing to work towards a low waste lifestyle. I am tempted to undertake an extensive analysis and write a full-fledged paper about this. I feel deeply inspired by similar works undertaken by scholars such as O’Connell (2021), Shannon (2019), and Christou (2009) but remain skeptical about the relevance of writing about my own experience. I also feel uneasy at the thought of exposing my vulnerabilities to the (often unfeeling) academic publishing system. But for the time being, I am grateful for this space that has allowed me to organise my thoughts and formally acknowledge the impact of this digital autoethnography project on my life.

Note

[1] Many supermarkets in the Netherlands have started stocking smaller portions of perishables but purchasing several small portions instead of one large portion usually means purchasing more plastic packaging, a compromise I wasn’t willing to make.

References

Atay, A. (2020). What is cyber or digital autoethnography?. International Review of Qualitative Research, 13(3), 267-279.

Christou, T. (2009). Dead, shed skin: An autoethnography. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 25(2), 38-47.

Dunn, T. R., & Myers, W. B. (2020). Contemporary autoethnography is digital autoethnography: A proposal for maintaining methodological relevance in changing times. Journal of Autoethnography, 1(1), 43-59.

O’Connell, L. (2023). Being and doing anorexia nervosa: an autoethnography of diagnostic identity and performance of illness. Health, 27(2), 263-278.

Warren, S. (2019). Chew, spit and speak: autoethnography and the eating disorder world (Doctoral dissertation, Memorial University of Newfoundland).