Negotiating Expertise: The Case of Operations Research

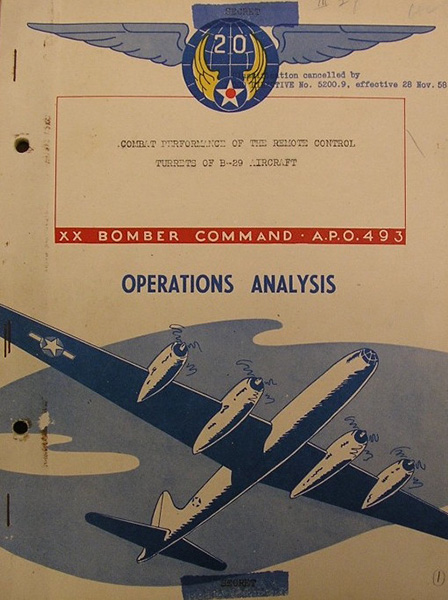

Among the most important and common questions that historians of science and STS scholars address is how technical cultures interact with various “lay” communities, such as policymakers, executive decision makers, juries, and public stakeholders. Within STS broadly, scholars have usually thought about these relations within an analytical framework of boundary negotiations. In this framework, technical experts do political work to stake out an epistemic terrain in which their claims will carry an unchallengeable authority. The idea of “science” is important in this framework, because it supposedly signifies (to historical and contemporary actors) knowledge that is uniquely authoritative and stands outside the influence of society and culture. My research on the history of “operational” or “operations research” (OR) has led me to question how well this model describes actual cultures of expertise. One of the prototypical sciences of decision making, OR originated in World War II in scientists’ scrutiny of military tactics and procedures. In the postwar period, a civilianized version of OR, directed at industrial problems, arose, accompanied by a body of formalized (i.e., mathematized) OR theory. Prior scholars have supposed that formalization constituted a move to consolidate OR’s scientific authority. I believe that to understand the development, we require an entirely different understanding not only of OR’s history but of how cultures of expertise operate. (read more...)