“India’s Gig-work Economy” Roundtable

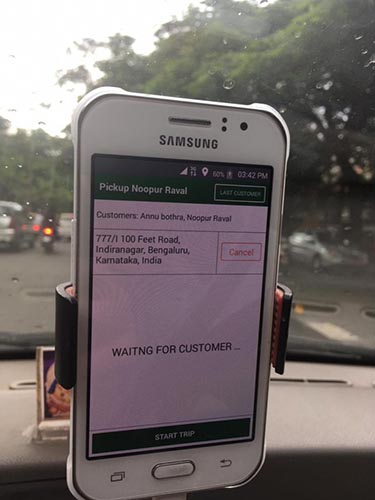

This roundtable discussion marks the end of our series on India’s Gig-work Economy. In this discussion, we reflect on methods, challenges, inter-subjectivities and possible future directions for research on the topic. Here are some highlights from the discussion. Listen to the audio track below or read the transcript for the full discussion Anushree (researcher, taxi-driving in Mumbai): “Something that came out during field work was the flow of workers from traditional services to app-based services which kind of happened in phases and all these platforms have played a different function in the history of this. While the radio taxis were more important in teaching workers to become professionals in the service economy the new platforms have given them a larger customer base and hired access to audience.” (read more...)