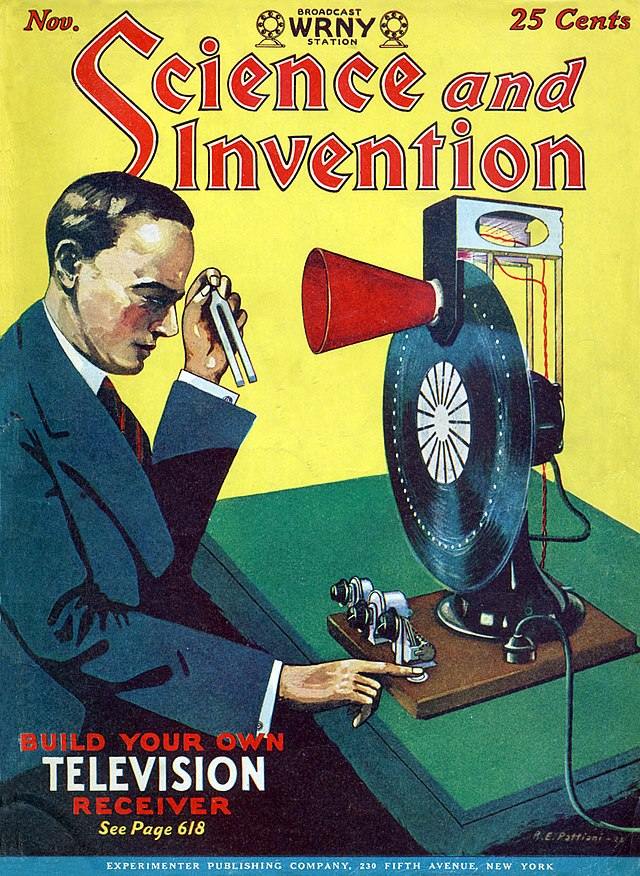

Memorializing Eruption

Perched on a makeshift stage, a trio dressed in wool ponchos sings pirekuas, the region’s most acclaimed and loved musical genre in a mix of Purépecha and Spanish. Despite their upbeat and soft-sounding melodies, the lyrics of the songs describe a time of fear and destruction when, eighty years ago, the Paricutin, the world’s youngest volcano, emerged from a cornfield and devastated the region. Stallkeepers are busy selling quesadillas, chips, sodas, and beers to the expectant crowd, gathering around a bonfire installed inside a miniature volcano. This contrast between apparently joyful festivities and solemn commemoration marks the evening’s atmosphere in Angahuan, Caltzontzin and San Juan Nuevo in Michoacan, Mexico. Several uniformed and heavily-armed municipality police stand nervously watching the horizon. These days, this is fraught territory, as organized crime groups dispute control over the area. This is also the first time that an event like this is staged on-site at the place known locally as las ruinas , a shorthand for the remains of the old San Juan Parangaricutiro church, the only surviving structure of an entire town buried under the thick and rugged lava. (read more...)